Fruit and beer have long had a relationship which extends through history to the earliest known fermented beverages. Keeping with this tradition, it seems that it would be a rare homebrewer who has never experienced the urge to incorporate some type of fruit into one of their recipes. I know for a fact that if you looked back through my first 20 to 40 brew logs you would find an American wheat with blueberries, a kiwi pale ale, and a raspberry porter. In fact, as a young homebrewer, I remember those beers as being some of my tastiest batches! It’s actually a little comical to me now, that at a time when I still didn’t have a good grasp on recipe development, I was so eager to add even more ingredients to an already complex process. But that’s the nature of brewing, we love to experiment, and in doing so we learn.

Although fruit can be incorporated into practically any style of beer, in my opinion, it really finds a special home in sour beers. Most fruits are naturally acidic, and it is this fact that tends to make fruit flavors taste brighter and more natural in sour beers than the same fruits would taste in beers with a higher pH. Winemakers refer to wines without enough acidity as flabby, and this same dull muddled fruit presentation tends to occur in beers without a supporting level of acidity. Like this description, we will be borrowing a number of concepts from winemakers throughout this article. This may come as no surprise when we consider the whopping amounts of fruit that some sour beer styles can incorporate into their fermentations.

Although fruit can be incorporated into practically any style of beer, in my opinion, it really finds a special home in sour beers. Most fruits are naturally acidic, and it is this fact that tends to make fruit flavors taste brighter and more natural in sour beers than the same fruits would taste in beers with a higher pH. Winemakers refer to wines without enough acidity as flabby, and this same dull muddled fruit presentation tends to occur in beers without a supporting level of acidity. Like this description, we will be borrowing a number of concepts from winemakers throughout this article. This may come as no surprise when we consider the whopping amounts of fruit that some sour beer styles can incorporate into their fermentations.

Article Contents

With this road-map ahead of us, let’s get started with an exploration of the characteristics that make fruit both an enticing and challenging ingredient within our sour beers.

Characteristics of Fruit

I’d like to start our discussion of fruit with a brief background on what fruit is and why flowering plants grow fruit in the first place. It’s an interesting question: Why would plants invest a lot of time and energy into growing something which another species will eat? The answer arises from what happens once a piece of fruit is eaten: An animal will go about its business, traveling into new areas and, as animals tend to do, defecating along the way. And it’s in this last part that our answer can be found: By providing animals an enticing and nutritious meal, a plant gets to have its seeds transported into new areas and deposited with a fresh batch of fertilizer to kick off a healthy germination.

This line of thought also brings up a few topics that directly relate to fruit characteristics that we care about in brewing and blending. It is important to a plant that animals prefer not to try to eat its fruit before the seeds inside have fully matured and are capable of germination. Plants do this by building higher levels of acidity, bitter compounds, and tannins into un-ripe fruit. As fruit ripens and the seeds inside mature, the plant will encourage the fruit to be eaten by increasing the sugar content of the fruit, changing its color, and increasing the production of esters and other aroma compounds. Depending on the individual fruit, the acidity and tannin levels may drop as the fruit ripens, or these flavors may simply be masked by the increased sugar content (an important distinction when it comes to how such fruits will flavor our sour beers). Lastly, it is important to plants that the animals coming to them for a meal don’t decide to start eating their branches or crushing up and eating the seeds inside the fruit itself. Plants prevent this unwanted snacking by building the most abrasive tannins and often some chemicals that are actually mildly poisonous into the seeds and stems of the fruit. Let’s now take a look at some of these individual fruit characteristics in more depth.

This line of thought also brings up a few topics that directly relate to fruit characteristics that we care about in brewing and blending. It is important to a plant that animals prefer not to try to eat its fruit before the seeds inside have fully matured and are capable of germination. Plants do this by building higher levels of acidity, bitter compounds, and tannins into un-ripe fruit. As fruit ripens and the seeds inside mature, the plant will encourage the fruit to be eaten by increasing the sugar content of the fruit, changing its color, and increasing the production of esters and other aroma compounds. Depending on the individual fruit, the acidity and tannin levels may drop as the fruit ripens, or these flavors may simply be masked by the increased sugar content (an important distinction when it comes to how such fruits will flavor our sour beers). Lastly, it is important to plants that the animals coming to them for a meal don’t decide to start eating their branches or crushing up and eating the seeds inside the fruit itself. Plants prevent this unwanted snacking by building the most abrasive tannins and often some chemicals that are actually mildly poisonous into the seeds and stems of the fruit. Let’s now take a look at some of these individual fruit characteristics in more depth.

Calculating ABV Change

While not a myth per se, I often see discussions about fruit additions to beer that are erroneously rooted in the idea that any fruit added to the beer will increase that beer’s ABV measurement to some degree. While fruits additions contain sugar, which will be converted into alcohol, these additions also contain water, which will increase the volume of a beer. Therefore fruit additions can increase ABV, lower it, or leave it unchanged depending upon what the gravity of the juice inside the fruit happens to be. Luckily for those who would like to calculate this change, it is easy to do so. This calculation makes the assumption that any fermentable sugar in a fruit is contained within that fruit’s juice, but this is a safe assumption because most fruits do not contain significant levels of sugar or more complex carbohydrates within their pulpy, fibrous portions. Also, keep in mind that this estimation will work for whole fruit, puréed fruit, and fruit juice additions but will not work for dehydrated fruit.

In order to calculate ABV change, we need to know the volume and starting gravity of our beer as well as the gravity of our fruit’s juice and the approximate volume to be added. The easiest way to measure the gravity of fruit juice is with a refractometer. For an accurate result, select several pieces of fruit from the lot/batch you intend to use and press (or simply crush) them to extract some juice. This can be homogenized by stirring and then pipetted onto the refractometer for measurement. Remember to adjust your reading for temperature if using refrigerated fruit that is below the calibration temperature for your refractometer.

An affordable and easy to use juicer that I found on. Check out similar juicers here.

The second measurement we need is an approximation of what percentage of a fruit’s total weight is made up by its juice. The easiest way that I have found to measure this is with a juicer and a scale. Simply weigh a sample of whole fruit, then run it through a juicer and weigh the resulting juice.

With these measurements in hand, you can use our included calculator to easily estimate ABV change.

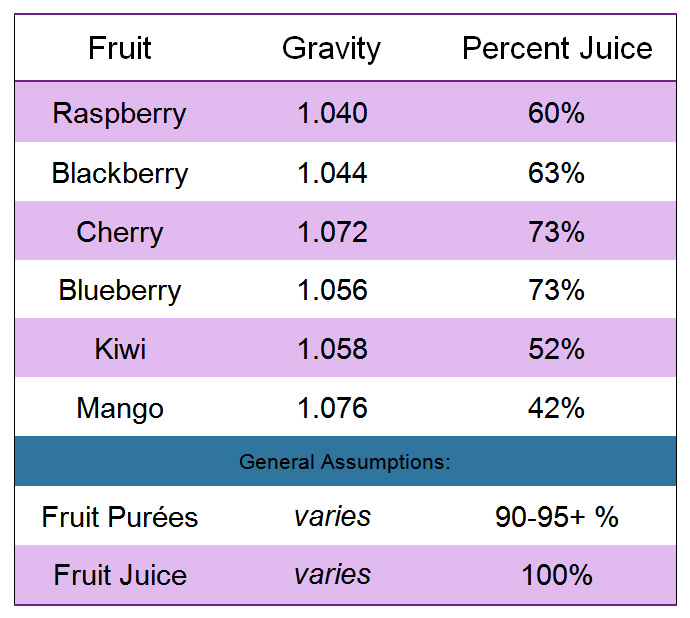

While writing this article, I decided to swing by a local grocery store and pick up a handful of different fruits in order to test their gravities and the approximate percentage of each that is juice. Here are the results for the fruits that I tested. Keep in mind that these measurements are likely to change with any individual fruit harvest.

(If you do not have the ability to juice a portion of the fruit for use in our calculator, you can plug in an estimate by entering 100 into the fruit sample weight field, and the corresponding percentage estimate into the juice sample weight field.)

Fruit Additions ABV Change Calculator

Titratable Acidity (TA) Calculator

Acidity

Fruits contain a variety of organic acids, with the most common being malic, citric, and tartaric acids. Different types of fruit tend to contain a higher concentration of one variety of acid over others, but practically all fruits contain at least trace amounts of all three of these acids. Malic acid is the primary acid of apples, watermelons, apricots, peaches, blackberries, raspberries, blueberries, and cherries. Tartaric acid is the primary acid of grapes, but can also be found in cranberries, apples, apricots, prickly pears, mangos, and many other fruits. Citric acid is the primary acid of citrus fruits such as grapefruit, oranges, lemons, and limes. Additionally, all of the common berries and many other fruits also contain citric acid, a fact that will have implications when considering malolactic fermentation.

Winemakers Acid Blend is a food grade blend of the three most common fruit acids.

In fresh ripe fruit, acidity is often tempered in its flavor by the presence of sugar. Therefore, it’s important to consider the acid content of a fruit when choosing how to blend it into a sour beer. After refermentation, the sugars which may have hidden the strength of a fruit’s acids will be gone, leaving the acids to stand on their own. If a brewer wants to be able to predict whether a given fruit will raise or lower the acidity of a blend, they can measure the titratable acidity of both their beer and the fruit’s juice. If the TA of the juice is higher than the TA of the beer, the fruit will increase the beer’s total acidity after refermentation. For more information on the process of measuring titratable acidity, check out our article on The Fundamentals of Sour Beer Fermentation.

Malolactic Fermentation

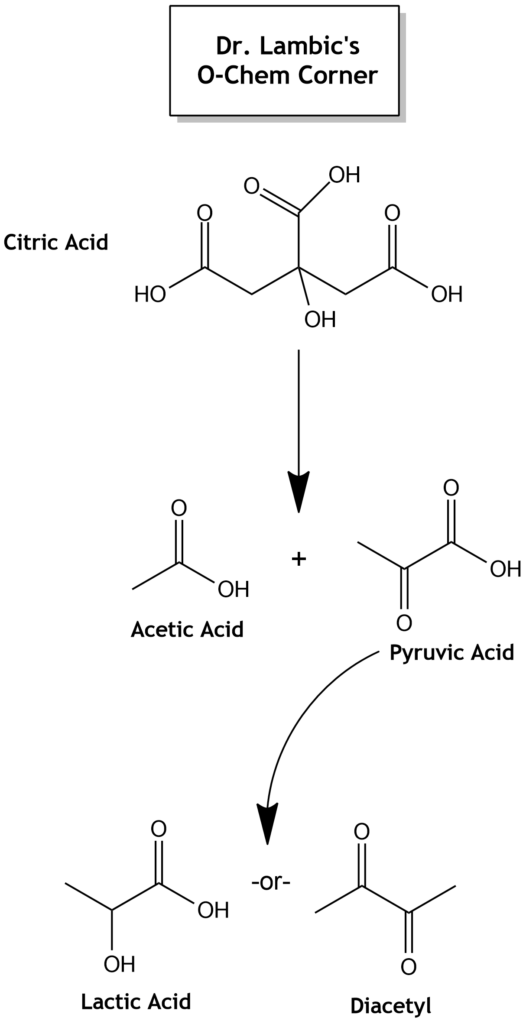

A simplified pathway for the breakdown of citric acid to acetic acid and other metabolites by malolactic bacteria.

A variety of bacteria can metabolize some of the natural fruit acids into other compounds. Winemakers make use of the bacteria Oenococcus oeni to induce malolactic fermentation in wines high in malic acid. This is done because lactic acid is considered to have a softer taste than malic acid. In sour beer, most strains of both Lactobacillus and Pediococcus can also perform malolactic metabolism. Due to this, it is common after blending fruit into sour beer for the acid balance to shift from malic to lactic over a period of several weeks to several months, a change which is generally beneficial for the flavor profile of the blend. It is interesting to note that bacteria with malolactic activity tend to produce both acetic acid and diacetyl in the presence of citric acid. While the buttery flavor of diacetyl may be a positive note in classic chardonnays, it is considered to be an off-flavor in sour beer. As a result, it is best to plan for a minimum four to six week aging period after blending fruit into a sour beer to allow Brettanomyces the opportunity to reduce this compound. This consideration is especially important if a fruit high in citric acid is being incorporated into a blend.

Tannins

Fruits are a natural source of several varieties of tannins. These compounds do not have a true “flavor” but rather create the perception of dryness and astringency on the palate. Like oak and other barrel woods, the parts of fruit which are typically eaten contain mostly hydrolysable tannins. These tannins tend to be pleasant on the palate from the very beginning, adding complexity and structure to the body and mouthfeel of a sour beer. On the other hand, the seeds and stems of fruit are often high in condensed tannins, which tend to be harsh on the palate, with high concentrations producing a dry, rough, cottonmouth sensation. Pressed fruit juice will typically add very little tannin to a blend while purées may have a low to medium tannin content depending upon how they are processed. Whole fruit has the potential to add the greatest concentration of tannins to a blend with the degree of tannin extraction based upon contact time with the bulk matter of the fruit. Care should be taken with any fruit high in seed content (such as many briar berries) as extended aging times can leech harsh levels of tannin into the beer. For more information on tannins in sour beer, check out our article dedicated to the topic.

Color

Three American blueberry sour beers. Photo courtesy of Jimmie Jackson.

The fruit compounds that can lend color to a blend typically fall into a class of molecules called anthocyanins. These pigments are pH sensitive and most often appear to be red, purple, or blue. While some varieties of fruit have colored juice that is high in anthocyanins, the skins of these fruits will also contain a high concentration of these compounds. Therefore, like tannins, contact time with whole fruit skins will increase the extraction of color compounds into a blend. In most cases, the low pH of sour beer will cause the pH sensitive anthocyanins to appear red or purple as opposed to blue (this is why blueberry sour beers always appear red). The acidity of sour beer also helps to preserve color compounds, although with time these compounds can settle out of a beer or break down into colorless metabolites, causing vibrant colors to fade.

Other Fruit Compounds

Of course, fruits offer much more to a sour beer than sugar, acidity, and tannins. As blenders, it is the wide variety unique flavors and aromas that fruits can provide which make them such an appealing ingredient. In general, these esters, phenols, and more exotic flavor compounds hit their maximum concentration at the peak of ripeness or just beyond that point.

In addition to the flavors we easily recognize and expect from fruits, there are a few extra flavors that may be unexpected. For example, many fruits contain a significant concentration of phenols and phenolic acids. Brettanomyces can transform these compounds into more of the classic barnyard, leather, and funk that we appreciate in certain blends. On the other hand certain fruits such as strawberries can be notoriously difficult to work with in sour beer due to these bio-transformations, which in the case of strawberries often create plastic, medicinal, or rubber-band aromas.

A very pleasant example of an unexpected transformation is the baking spice / cinnamon aroma that can accompany the use of cherries and other fruits such as pineapple in sour blending. Over the last few years there has been a fair amount of interest in the wine industry surrounding some organism’s ability to cleave unique esters free from glycosidic bonds to sugar. Many fruits have a high concentration of such glycoside bound aroma molecules and unique organisms such as Wickerhamomyces and certain strains of Brettanomyces have enzymes which can break these bonds, releasing a variety of unexpected yet appealing aromas and flavors into our fermentations.

A very pleasant example of an unexpected transformation is the baking spice / cinnamon aroma that can accompany the use of cherries and other fruits such as pineapple in sour blending. Over the last few years there has been a fair amount of interest in the wine industry surrounding some organism’s ability to cleave unique esters free from glycosidic bonds to sugar. Many fruits have a high concentration of such glycoside bound aroma molecules and unique organisms such as Wickerhamomyces and certain strains of Brettanomyces have enzymes which can break these bonds, releasing a variety of unexpected yet appealing aromas and flavors into our fermentations.

Lastly, it’s worth mentioning that the inclusion of certain fruit seeds or pits can contribute unique flavors to a blend. The classic example of this is the use of whole cherries in kriek blending. The cherry pits in these blends create an almond / marzipan flavor which is a hallmark flavor of Lambic krieks.

Sourcing and Processing Fruit

Before we can add fruit to our sour beers, we have to decide what form and type of fruit we would like to add, and then source said fruit. While a supermarket or local fruit stand may suffice for homebrewers making a five gallon batch, farmers markets and wholesale contacts will be required for professionals who may need to source hundreds or even thousands of pounds of fruit for a project.

Fresh Whole Fruit

When planning for the use of fresh whole fruit, it’s important for brewers to keep in mind that these are seasonal products. For logistic and economic reasons, large quantities of fruit are best to source locally or from farms within a reasonable shipping distance of the brewery. If a brewery does not intend to freeze fruit for storage, then they must have the beer or beers that they intend to use for blending ready when the fruit also becomes ready. Talk to local farmers and suppliers about their products, they will both be able to help you plan and provide valuable information about the fruits they grow.

The first step in handling whole fruit is to wash the fruit to remove any excess dirt or chemical residues. This is also the time to remove any bulk stems or leaves from the fruit.

After cleaning, we want to break the fruit open so that the juice and other contents have the opportunity to be exposed to both the beer and its resident microbes. This processing can range from simply slicing a piece of fruit in half, to crushing it open, to reducing it to a purée. Whether or not storage is a goal, some brewers advocate freezing fruit before adding it to a blend in order to rupture cell walls and make the fruit more accessible to the beer. Depending upon our goals for tannin and flavor extraction, seeds may be removed or left in the whole fruit.

Two common devices which can be used to process whole fruit are crusher / de-stemmers and handheld immersion blenders. Crusher / de-stemmers can be motor driven or hand cranked and come in varieties either meant for grapes and berries or for larger stone fruits such as peaches and plums. While these devices are capable of processing large quantities of fruit in relatively short periods of time, they come with higher price tags as well. Handheld immersion blenders are less costly, but are typically used to work through smaller quantities of fruit (such as may be held within a 5 gallon bucket) at a time.

A wide variety of potential yeast and bacteria species may be living both upon and within whole fruit. Some brewers prefer whole fruit for this reason, considering any flavor contribution from the resident microbes to be a beneficial influence to the terroir of their blends. Other brewers seek to reduce the impact of these microbes. This is another potential benefit of first freezing whole fruit before use, as the freezing and thawing process will kill of some (not all) of the microbes present. Thoroughly washing the fruit before use is another method to help to reduce the cell counts of any surface yeast and bacteria.

At the time of this writing, I have made sour beer blends using whole fresh fruit, whole frozen fruit, fruit purées, and fruit juice. While all of these options have resulted in delicious beers, I think there is something special to be said for the use of fresh whole fruit. Of all the options, using fresh fruit is probably the biggest challenge (read: pain in the ass) due to its requirements for timing, processing, actually getting it into the beer, and getting beer off of the fruit. That being said, I personally find that the delicate aromatics and tannin contributions of whole fruit make for some of the very best blends. There are a variety of reasons why fresh whole fruit may not always be an option for professional brewers. But when home brewing, I definitely encourage you to give fresh whole fruit a try. If for no other reason, its acquisition and handling gives a brewer a connection to the ingredients in a way that, for me, harkens back to a more ancient time when beer was a central good of the first agrarian societies.

Frozen Whole Fruit

In many cases, whole frozen fruit may be an attractive option for sour blending. Often, frozen fruit has already been cleaned and de-stemmed / de-seeded. Frozen fruit also may be available during times of the year when fresh fruit is not. Typically, due to the extra processing, frozen fruit will cost more per pound than fresh fruit. In many cases, frozen fruit will also provide a similar tannin, acid, and sugar contributions to a sour beer blend as fresh whole fruit. Once, thawed such fruit would be added to a blend in the exact same manner as processed fresh fruit.

Puréed Fruit

The popularity of fruit as a beer ingredient has led to a growing market for high quality fruit purées. These products may come canned for homebrewers or in larger format containers for professional brewers. My local homebrew shop has carried products from Oregon Fruit (now labeled as Vinter’s Harvest for homebrewers and home winemakers) and I can personally attest to the high quality of their purées, which in my experience provide excellent fruit flavor and aroma to a blend.

The popularity of fruit as a beer ingredient has led to a growing market for high quality fruit purées. These products may come canned for homebrewers or in larger format containers for professional brewers. My local homebrew shop has carried products from Oregon Fruit (now labeled as Vinter’s Harvest for homebrewers and home winemakers) and I can personally attest to the high quality of their purées, which in my experience provide excellent fruit flavor and aroma to a blend.

As a general rule, when a company selects fruit to purée for use in brewing or winemaking, they do so with flavor and aroma quality and consistency in mind. Purées therefore offer consistency, sanitation, ease in handling and measurement, and stability / ease of storage to fruit as a blending ingredient. Most purées will provide less tannin contribution to a blend than whole fruit due to the removal of much of the bulk matter and fiber from the source fruit.

Fruit Juice

Fruit juices and concentrates receive more processing than fruit purées, and as such tend to provide a less complete portfolio of fruit flavors to a blend.

Red Jacket produces an unfiltered series of fruit juices that I have used successfully in blending (with additional whole fruit).

Juices and concentrates will typically be devoid of any solid matter, and will therefore provide little to no tannin content to a beer. These products are also often fortified with additional sugar, allowing their producers to create more product with less source fruit. As a result, juices and concentrates tend to offer less acid and less overall fruit flavor and aroma per pound than an equivalent weight of whole fruit or purée. Of course, there are exceptions to this rule, and local farms as well as some national suppliers may provide fruit juices or concentrates that are of high flavor and aroma potential. Regardless of the flavor characteristics of an individual juice, be cautious with juices that contain preservatives or stabilizers as these chemicals can interfere with refermentation in some cases.

In my experience, fruit juices and concentrates can be incorporated as a component in a sour beer blend with one of two goals in mind. The first goal would be to add a subtle fruit character to a blend without the hassle of sourcing whole or puréed fruit. The second goal would be to add an additional source of fruit flavor and aroma in order to round out / add complexity / fill in gaps in a blend. In these cases, a juice or concentrate would be added along with other sources of fruit.

Fruit juices and concentrates can run a gamut of possible gravities, so it is best to always measure the sugar content of these ingredients before adding them to a blend. In the case of concentrates, these products have the potential to dramatically increase the ABV of a blend.

Dehydrated Fruit

When it comes to brewing and blending, there is not a lot of standardization among producers of dehydrated fruit. These products can be successfully incorporated into a blend, but some degree of experimentation will always be required to hone in on the best processing methods and usage rates for varying products. When using dehydrated fruit, here are a few useful tips to keep in mind:

- Dehydrated products will add sugar without additional water content, generally raising the ABV of a blend.

- Some dehydrated fruits will be coated with oils to prevent clumping in the package / sticking to machinery. These oils can create problems with head retention and staling of the beer. If present, they can be removed to some degree with a hot water rinse.

- Dehydrated fruits will expand once added to a beer, potentially reducing the volume of a blend more than casual estimates would suggest.

- Dehydrated fruits will add acid and tannin content to a blend, but their impact in these categories can be difficult to estimate.

While I have not personally used dehydrated fruits in sour beer blending, I have tasted beers made using these products. I would say as a general observation that while these beers had fruit flavors, these flavors were not representative of whole, unprocessed fruit. As a blender, I would suggest conducting several small batch tests using a dehydrated fruit product before committing a well crafted sour base beer to a full scale blend.

Fruit Extracts

These products are created using a variety of methods meant to concentrate fruit flavor or aroma without sugar content. Every extract will vary to some degree in the particular aspects of the source fruit that are captured. Fruit extracts, when used in isolation, tend to produce somewhat one-dimensional fruit flavors or aromas that in my opinion do not taste very natural. My recommendation would be to only use fruit extracts to help fill in gaps, if any, left after aging a sour blend on whole fruit or purée. As with dehydrated fruit, brewers will need to experiment with various extract products in small blend scenarios to determine if and how they will benefit a beer before committing a full scale blend to their use.

Creating Fruited Sour Beer Blends

Once fruit has been sourced, processed, and had any measurements that a blender deems pertinent made, it will be time to actually put the fruit into the beer (or vice versa)!

Avoiding Excess Oxygen

Just like the blending of individual beers, which may occur before or in tandem with fruit blending, a brewer will want to take steps to ensure that their blend remains in the best possible health. Regardless of the equipment being used, one of the keys to keeping mature sour beer in the best possible condition is oxygen avoidance. Whether using carboys, barrels, or stainless tanks, a brewer may choose to add fruit to a beer already in the vessel or rack beer onto fruit already in the vessel. In either case the two best ways to avoid oxygen pickup are to:

- Use carbon dioxide or other inert gases to displace oxygen in the vessel.

- Avoid excess splashing / aeration of beer during transfers.

With these general practices in place, the specific methods a brewery uses to actually combine fruit with beer will vary significantly based upon their individual needs. You don’t have to drive yourself crazy with this. The active re-fermentation of fruit sugars will help yeast to take up or scrub out excess oxygen after blending, so if you’re being at least minimally conscientious about your practices, your beer should remain in good shape.

Fruiting Rates

When it comes time to choose how much fruit to use in an individual blend, a brewer has a wide range of options. At the lowest usage rates, fruit can offer subtle background notes that may be difficult to distinguish from fermentation characteristics, while still enhancing complexity. On the other end of the spectrum, brewers can include so much fruit in a blend that it begins to have more in common with a fruit wine than a beer. In many professional situations, a brewer’s license will prevent them from legally using fruit for more than 50% of the total fermentable sugar source. I have included this estimation in our fruit usage calculator as a tool to help brewers facing these restrictions from accidentally doing anything illegal. Luckily, homebrewers are not bound by such restrictions and can experiment with blending completely hybrid beer/wine/mead beverages or other unique creations.

These are photos from a raspberry sour intended to mimic the higher-end of fruit Lambic usage rates. 15 lbs. of whole red raspberries were blended with 5 gallons of base sour beer.

I have discussed general usage rates for fruit in several articles on the site, but I would like to elaborate on these concepts a bit during this treatment of the subject. As a general rule, most fruiting rates of 0.5 lbs per gallon (whole fruit weight) or less will provide a subtle fruit character that will be detectable yet still in the background. There are exceptions to this rule and certain very intense fruits such as red raspberries, cherries, boysenberries, or tart grapes can create an assertive character even at these lower rates. Stepping up from this, usage rates of about 1 lb. per gallon typically yield fruit flavors that are in balance with malt characteristics and other fermentation characteristics but may begin to showcase themselves as well.

Once we go higher than 1 lb. per gallon, we begin to enter the territory originally established by fruit Lambics. Rates of 2 lbs. per gallon tend to definitively showcase the fruit, creating an intensity of flavor that distinctly out-competes all but the most intense fermentation characteristics. This is not to say that drinkers will not still be able to taste components from the rest of a beer’s recipe and fermentation at these fruiting rates, just that the sheer amount of fruit flavor will take center stage. Pushing above this, we enter a region of fruiting that begins to establish a number of very distinctly wine-like characteristics in a blend. Some Lambics and American sours use rates that fall in the 3 to 4 lbs per gallon range or above and these beers inevitably take on some vinous and intense fruit characteristics.

I would like to bring up a concept about fruiting rates that has to do with how intensity of flavor can become a double edged sword. In a way, not only can higher rates of fruit usage create an intensity of flavor that hides more subtle components of the base beer, but these rates can actually begin to hide characteristics of the fruit itself. The threshold point at which a fruit’s high notes become too intense to taste the full profile of fruit flavors available will vary for every fruit and for every taster. But as a general rule, if a fruit blend is coming across as one-dimensional, consider lowering the fruiting rate for future blends.

Re-fermentation

Regardless of the processing and rate chosen, once fruit has been added to a sour beer blend, any live microbes within the blend will begin to ferment the sugars being added by the fruit as well as producing bio-transformations upon other fruit components such as acids, esters, and phenols. The period between a fruit addition and the complete fermentation of its sugars can be a sensitive time for a sour beer. Because our general recommendation is to add fruit to base beer that is already well developed and free of defects, we would prefer to not introduce potential off-flavors during the new round of fermentation that will now occur.

The best way to avoid the creation of off-flavors such as diacetyl, acetaldehyde, or fusel alcohols during fruit re-fermentation is to add a fresh pitch of healthy yeast, either Saccharomyces or Brettanomyces at the same time we are adding our fruit. This helps to ensure that the majority of fruit sugars will be fermented by these organisms as opposed to bacteria such as Pediococcus, which tend to end up in a “last man standing” situation in aged sour beers.

My preference, when dealing with fruited sour blends, is to allow these beers to age for a minimum of 4 to 8 weeks before serving. This time, which I start counting after refermentation has completed, gives yeast cultures in the blend time to clean up any potential off-flavors which may spike after the addition of fruit.

Sometimes long contact times can work well for a beer. This is a blended golden sour that aged with 1 lb. per gallon of Niagara grapes for 8 months. I was very pleased with the flavor balance and tannin contribution from this treatment.

Contact Time

When we think about contact time with fruit, there are a couple of characteristics to consider:

The first of these is fruit sugars. Unless the goal of your fruit addition is to provide some balancing sweetness for a draft sour beer, you will generally be leaving the fruit in the beer for long enough for a complete refermentation of its sugars to occur. This refermentation will typically be complete in 2 to 4 weeks, with shorter time frames possible if pitching fresh yeast cultures along with the fruit.

My second consideration is fruit esters and unique fruit flavors. These actually make their way into your sour beer fairly quickly. As a general rule, by the time refermentation has occurred, you are likely to have already extracted the majority of fruit esters and other aromatic compounds into the beer. Like these aromatic and flavor compounds, the majority of fruit acids will also be extracted into your beer within 2 to 4 weeks of contact time. Keep in mind that the speed at which these compounds make their way into your sour beer will increase proportional to how thoroughly the fruit is sliced, diced, crushed, or puréed.

A third consideration for contact time is the extraction of tannins. These compounds slowly leach out of the skins, seeds, and fibrous/pulpy portions of the fruit over extended periods of time. In my experience, tannin extraction seems to peak somewhere between 3 to 6 months of aging time on fruit.

My last consideration is in regard to any specialty seed/pit flavors such as those provided by cherry seeds. These flavors tend to be extracted on time frames similar to those of tannins. As a general rule, I think of tannins, color compounds, and seed flavors to be extracted at approximately the same rate, peaking after 3 to 6 months of contact time.

Punching Down / Avoiding Mold

When whole or partially crushed fruit is added to beer, portions of the fruit tend to create a mat which floats near or above the surface of the beer. The fruit that rests above the liquid surface creates an inviting environment for mold growth if any oxygen (including low level micro-oxygenation) is present. Winemakers use a process called “punching down” to both break up these mats and press them below the liquid surface. Fruits tend to float not only due to their natural buoyancy but also because carbon dioxide becomes trapped within their tissues during fermentation. Punching down displaces this trapped CO2, making the fruit less likely to rise above the surface after refermentation slows and several punch downs have occurred.

In carboys, rather than punching down, I simply rock the carboy gently in order to swirl the contents and mix the fruit back into the beer. This process has the same effect of displacing trapped carbon dioxide bubbles, helping the fruit to rest lower in the liquid column with each treatment.

Mold requires some access to oxygen in order to grow, therefore regardless of whether punching down is employed, reducing oxygen exposure to sour beer aging with fruit is an important consideration to prevent growth of this unwanted family of fungi. It can sometimes be difficult to differentiate pellicle formation from mold growth. As a helpful reference, the Milk The Funk Wiki maintains a large gallery of photos comparing the two.

Base Beer Selection

When it comes to choosing a sour beer to blend with fruit, there are a few basic guidelines and very few, if any, rules. Here are a few guidelines and tips to consider:

An example home-made sour beer that was blended from two sour red and one sour blonde base beers, then aged on puréed blueberries and blackberries.

Fruit will typically be added to a mature sour beer. That is, a beer or blend that the blender is happy with, and could be drank on its own. Let’s say the plan is to add cherries to a Flander’s Red Ale. This style of base beer may take 6 to 18 months (or so) to become ready. The addition of cherries to such a beer should occur during the last months of the beer’s aging time, not at the beginning. Adding fruit to mature beer helps to promote fresh, bright, and full fruit flavors, many of which could be lost if the fruit was added at the beginning of fermentation and then allowed to age for many months or years.

- Fruiting should not be used as a way to fix flawed beer. In my opinion, its purpose should always to be to enhance a blend, not repair one.

- If aiming to create beers similar to fruit Lambics, a blend of 1 to 2 year old mixed culture or spontaneous golden sours should generally be used. It is important to utilize whole fruit at a rate of 2+ lbs. per gallon as well as base recipes that make use of aged hops, long boils, and some grain tannin extraction. These base beers should be tart to moderately sour, not abrasively sour.

- Remember that any citric acid present in the fruit (most fruits contain some citric acid) can be converted to both acetic acid and either lactic acid or diacetyl by microbes with malolactic activity. Therefore, blenders should use caution when choosing base beers with any discernible acetic acid / ethyl acetate character. Fruit additions are very unlikely to mask or dilute these characteristics.

- Many fruits will increase the acidity of the final blend, choosing a base beer that is less sour than may be desired for a finished beer is often prudent.

- Delicate fruits tend to showcase themselves best in golden sour beers without significant percentages of caramelized, roasted, or toasted malts. When choosing a red, brown, or black base beer, more intense fruits tend to showcase themselves more fully. Examples of such fruits include raspberries, cherries, and grapes. Fruiting rates may also be increased in more characterful base beers if the goal is to showcase the fruit’s unique flavors against a more aggressive backbone.

Second Fruiting

A number of sour brewers have begun experimenting with a process called second fruiting. Simply stated, this is the act of adding a second sour or farmhouse beer to the fruit left over from a previous sour beer & fruit blend. Second fruiting not only allows a blender to make fuller use of an expensive ingredient, it also can produce excellent results which tend to show off a different mix of fruit flavors between the first and second use.

While this practice offers a wide range of possibilities, one that tends to work very well for brewers is to:

- Create an initial fruit-forward blend by combining a mature sour beer with a relatively high ratio of fruit per gallon. These blends are often highly fruit forward with moderate to high acidity due to their fruiting rate.

- Create a second blend using the spent fruit (from the first batch) combined with a sour beer of more restrained / delicate acidity or with characteristics of a farmhouse ale or tart saison. These second blends tend show off a more subtle array of fruit flavors and often characteristics of the fruit that the initial blend was too intense to readily taste. These second fruiting beers, given their potentially lower acidity, may also become funkier or spicier with age.

Most professional brewers use this sequence with fresh whole fruit, however I have also tasted excellent homebrews which used purée in a second fruiting process.

Separating Beer From Fruit.

In many cases, the act of separating finished sour beer from the spent fruit can be one of the more challenging parts of the whole process. Luckily, with the right equipment and a little patience, this too can be made relatively easy.

I personally used to wait for my home made sour beers to settle to clarity in the carboy (usually after around 3 months of time spent on the fruit). In most cases the fruit will form two layers, a floating top layer and a layer of bottom sediment. I would use a racking cane with an inline stainless filter to pull the finished beer from between these two layers, allowing the inline screen to catch any little bits that made their way into the racking cane. This method worked alright but I would find that toward the end of the transfer, I would have to stop and clean out the screen several times. This was not only a time waster but also exposed the beer unnecessarily to more oxygen each time I needed to stop and restart the siphon.

I now use a fine stainless steel screen that completely encapsulates my racking cane for transferring sour beer from the carboy and this has improved my process, allowing for easier transfers with less potential oxygen exposure.

Professional brewers have a variety of options for removing fruited sour beer from barrels or stainless tanks. Barrel racking devices can be fit with stainless stain screens, while stainless fruiting / blending tanks can be fitted with false bottoms or racking ports to avoid the majority of fruit suspended above or below the beer. One clever creation, with directions here from Levi Funk of Funk Factory Gueuzeria, is a false bottom which fits into a standard wine barrel to aid in fruit separation.

After the separation of beer from the bulk of all fruit matter, some brewers, including most Lambic brewers/blenders, prefer to run the beer through a coarse filtration. This process is intended to remove any tiny fruit particles or bits of pellicle from the beer. If the filtration method is relatively coarse, the microbial population and delicate flavors of the beer should be minimally impacted.

For homebrewers who would like to perform a similar filtration, one method that will be minimally impactful is to run beer at low pressure through a Blichmann Hop Rocket packed with sanitized rice hulls from one keg to another. If dry hop character is desired, this method could be used with a bed of dry hops as well (also a great option for homebrewers looking to filter any dry hopped beers). Alternatively, small wine-grade filters such as the Buon Vino Super Jet can be used with coarse filter pads, although even these coarse filter pads tend to produce crystal clear beer and may impact delicate aromas and flavors.

Conclusion – Bringing It All Together

The creation of well planned and executed fruited sour beers is no small feat. It requires forethought, patience, experimentation, and attention to detail in order to guide a beer through not only one complex fermentation but two. That being said, excellent fruited sour beers are most easily born out of long term blending programs. By establishing a blending program, a sour brewer creates a pipeline that will allow sour base beers to be ready for blending at the times when fresh fruit is available. These programs also give blenders a variety of beers to choose from, allowing the flexibility to choose beers that will be complimented by fruit, rather than trying to shoehorn one specific beer into a fruit blend which may not be right for it.

It’s a big and bountiful world out there for fruited sour beer enthusiasts. The number of fruits available worldwide numbers easily into the thousands, offering virtually unlimited opportunities for new flavors!

Once a blending program has been established, the next step is to wait for both the right fruits and the right inspiration to strike. Many brewers, especially those with wine backgrounds, develop a natural ability to taste and build excellent blends. But for those without this level of experience, making some of the simple measurements and following the advice discussed in this article will help to avoid blends that become too sour, too acetic, or too one-dimensional (three of the most common faults I find in commercial fruited sours).

Remember not to underestimate the impact that different versions of the same type of fruit will have on your beers. The flavors of an individual harvest of fruit can vary significantly from season to season, and farm to farm (all before even considering different varietals). All fruits are not created equally. For example, lets say an American brewer creates a base blend that tastes spot-on like a Belgian Lambic (no easy feat in and of itself). If that brewer blends this base with American varieties of sour cherry, the resulting beer will not taste exactly like a Lambic kriek. This is because American Montmorency, Balaton, and other varieties of cherry do not taste all that similar to European Morello cherries. As brewers, we tend to focus our concentration on the classic ingredients of beer, but when it comes to fruited sour blending, it pays to start thinking like a winemaker. When we read sour beer descriptors such as “juicy”, “jammy”, or “dessert-like”, remember that the fruit itself has more to do with these impressions than the beer it was blended into. You may spend a year sampling and blending base beers, don’t only spend a minute tasting the fruit you’re going to put into it.

Once all of these initial decisions have been made and our fruit and beer have become intimately acquainted, I tend not to sample the blend until about 2 weeks after signs of refermentation have subsided. I figure this is the minimum time frame for the blend to clean up any off-flavors and stabilize. This initial tasting should be used to evaluate the beer for off-flavors, positive fruit flavors, acidity level and balance, tannin content, and fermentation characteristics. Based on your findings, you would then make a decision about how long the beer should continue to age on or off of the fruit before final packaging and serving.

Hopefully this article has been a helpful resource to guide both home and craft brewers through some of the most common processes and considerations to make when blending fruited sour beers. Fruited Lambics, as well as their American counterparts, have long been some of my absolute favorite sour beers to both drink and attempt to create. This article represents a distillation of what I have learned over the years through both my own experience and the experience of others. I hope that through reading it, you too will pick up ideas and inspiration for your next fruited sour beer. Good luck and happy blending!

Cheers!

Matt “Dr. Lambic” Miller

Like a delicious fruit pairs with a great sour beer, we recommend pairing this article with:

DESIGNING AND BREWING A BERLINER WEISSE

References

“Citric Acid.” Viticulture & Enology. UC Davis, 03 Jan. 2017. Web. 10 Feb. 2017.

Goodwin, Jay. “Question About Fruit Additions.” Message to the author. 30 Jan. 2017. E-mail.

Guinard, Jean-Xavier. Lambic. Boulder, CO, USA: Brewers Publications, 1990. Print.

Haminiuk, Charles W. I., Giselle M. Maciel, Manuel S. V. Plata-Oviedo, and Rosane M. Peralta. “Phenolic Compounds in Fruits – an Overview.” International Journal of Food Science & Technology 47.10 (2012): 2023-044.

Kearney, Breandán. “15 Common Off Flavours in Beer (and How To Identify Them).” Belgian Smaak. 08 May 2016. Web. 10 Feb. 2017.

Rivard, Dominic. The Ultimate Fruit Winemaker’s Guide: The Complete Reference Manual for All Fruit Winemakers. 2nd ed. Bacchus Enterprises, 2009. Print.

“Soured Fruit Beer.” Milk The Funk Wiki. Milk The Funk, 11 Jan. 2017. Web. 10 Feb. 2017.

Tonsmeire, Michael. American Sour Beers: Innovative Techniques for Mixed Fermentations. Boulder, CO: Brewers Publications, 2014. Print.