Hello Sour Beer Friends!

Many of you who follow my articles will probably already know that I am a huge fan of the oude kriek lambic style. There is something about the interplay between the high acidity, bright fruit flavors, and layers upon layers of Brettanomyces funk that just does it for me. Add to this an oude kriek’s sessionable ABV, crisp tannins, tasty almond flavors, and dry refreshing finish and you’ve got the complete package… A damn amazing beer that I could drink every single day.

Many of you who follow my articles will probably already know that I am a huge fan of the oude kriek lambic style. There is something about the interplay between the high acidity, bright fruit flavors, and layers upon layers of Brettanomyces funk that just does it for me. Add to this an oude kriek’s sessionable ABV, crisp tannins, tasty almond flavors, and dry refreshing finish and you’ve got the complete package… A damn amazing beer that I could drink every single day.

While kriek is the most commonly produced fruit lambic, and a number of fantastic krieks exist on the market, there are a handful of examples that, in my opinion, stand out above the others. It is among this short list of truly world-class krieks that you will find one of my favorite beers, Cantillon Kriek 100% Lambic Bio. Since beginning to write for Sour Beer Blog nearly a year ago, I have probably drank around a dozen examples of this beer. Despite this, I have yet to write about the kriek because most beer geeks and sour beer fans already know how good it is, holding Cantillon products in an almost spiritual reverence… With that said, lately I have been feeling that to continue to avoid writing about Cantillon Kriek would be like ignoring a dear old friend of mine. So I have decided to write this review not from the viewpoint of a beer that needs to be promoted, but rather simply as a celebration of what makes the beer great.

Cantillon Kriek begins its life in the same way as all of Cantillon’s traditional lambic beers. A blend of around 2/3 pale malted barley is combined with around 1/3 un-malted wheat. This mixture is mashed using a process unique to lambic breweries known as turbid mashing. During the turbid mash, portions of the liquid portion of the mash are pumped out of the mash tun and boiled before being re-added. Each time the boiled liquid goes back into the tun the temperature of the mash is raised by the addition, and via this process the mash proceeds through all of the temperature steps required to convert the malt’s starches and proteins into useful nutrients for a variety of microorganisms.

This turbid mash is followed up by a sparge that is hotter than what is usually employed by brewers of other styles. This hot sparge extracts astringent tannins from the grains that would be considered a flaw in any other style of beer, but in this case these tannins help to add complexity to the body and dryness to the finish of lambic beers much in the way tannins from grape skins are an integral part of a red wine.

The Boil Kettle at Cantillon – Photo by Kevin Desmet @ Belgian Beer Geek

This wort undergoes a long boil (about 4 hours, or until 25% of the volume is reduced) to which aged hops are added at a rate of around one ounce per gallon. These aged hops help to restrain the activity of the bacteria Lactobacillus during the beer’s fermentation so that the beer doesn’t become too acidic too quickly. As hops age, their acids and oils become oxidized and these components add a characteristic to lambic beers which can sometimes taste lightly cheesy, papery, or savory. Occasionally, lambic brewers will also include a portion of fresher noble hops into their boils. These hops don’t add much in the way of bitterness but may liven up the hop flavors of the base lambic being produced.

Wort Cooling in Cantillon’s Coolship – Photo by Kevin Desmet @ Belgian Beer Geek

The result of this turbid mash, hot sparge, and long boil with aged hops is a wort that is rich in both simple and complex sugars, proteins, tannins, and oxidized hop oils. This wort will provide nutrition to a host of microorganisms which are involved in the beer’s fermentation and aging. Cantillon cools this wort by pumping it into a traditional shallow and wide vessel called a coolship. This open-topped vessel, located in the brewery’s attic, allows the wort to cool overnight while it is exposed to outside air which passes through the space. During this time, the wort picks up both wild bacteria and yeast from the air. After cooling, the wort is pumped into oak barrels, pipes, and other variously sized oak vessels. These vessels also host microorganisms which will help to ferment the wort. I believe that, in general, a lambic brewery’s house flavor originates from the microbes in its barrels while batch to batch variation may be created by the random strains picked up from the air.

Aging Lambic Barrels at Brasserie Cantillon – Photo by Kevin Desmet @ Belgian Beer Geek

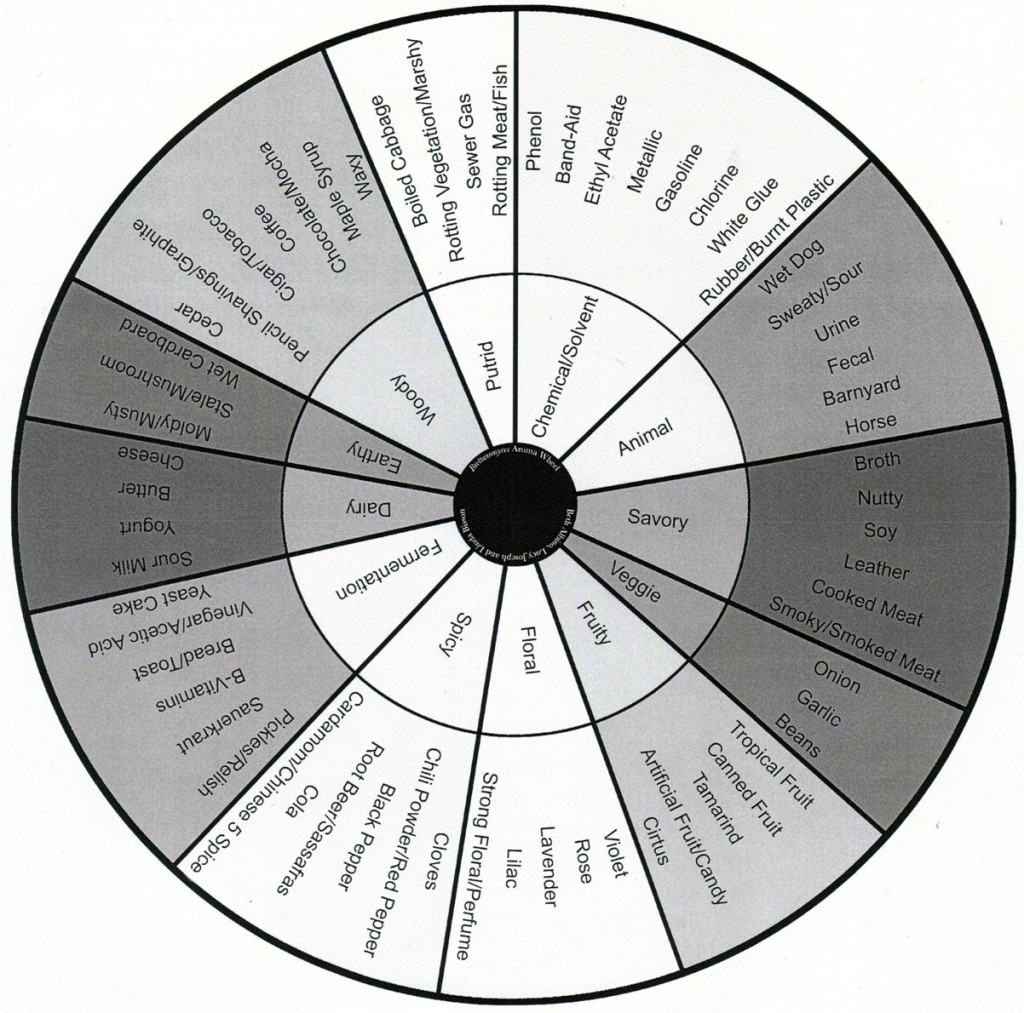

The beer which results from these processes, simply called lambic, ages within its barrels for up to several years as it slowly becomes sour and develops a wide range of aromas and flavors. These characteristics, many of which are the result of the Brettanomyces family of yeast, can range anywhere from floral and fruity, to musty, leathery, woody, sweaty, cheesy, or to even funkier possibilities like medicinal, smoky, or fecal. Not all of these options are desirable for inclusion in a kriek blend and some barrels that develop unpleasant flavors or turn to vinegar will eventually be dumped. Cantillon’s Kriek Lambic Bio is largely blended from lambic that has aged for between one and two years. As with any blend, the individual barrels are chosen based on the condition of the beer in order to produce the flavors desired by Cantillon’s fourth-generation owner and master blender, Jean Van Roy.

Cantillon Kriek’s key feature, it’s fantastic cherry character, is obtained by adding a cultivar of European Morello tart cherries called Kellery to the lambic beer at a rate of about 2 lbs per gallon. At Cantillon, this process takes place within pipes, which are large oak or chestnut barrels that can hold around 170 gallons of beer. Each pipe’s batch of cherries, around 330 lbs, gets exposed to two batches of blended lambic, with the second batch extracting further fruit essence not picked up by the first batch. These two batches are then blended together along with a small portion of young lambic before bottling. This young lambic adds the sugars needed for the beer to properly carbonate in the bottles, which takes about 3 to 5 months of conditioning time.

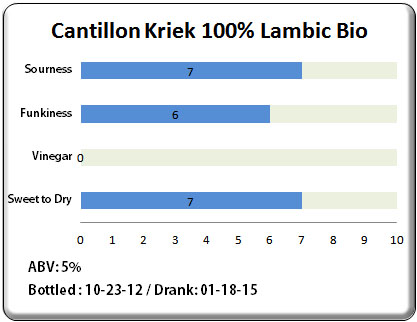

Now that we have a basic idea of how a Cantillon Kriek is produced, I’d like to share my most recent tasting of the beer. This was a bottle dated October 23rd, 2012, which I opened last week. The kriek poured a deep, crimson, red and was highly carbonated, forming several inches of rocky, pink head. The first aromas I picked up were those of Brettanomyces, specifically: a mixture of leather, damp earthy soil, musty horse blanket, and savory broth. Next up, were the flavors of fruit: sweet-esters, cherry pie and cherry jam, fresh squeezed cherry juice, red wine, and oak. Continuing to smell the beer brought out the most subtle aromas: flowers, sourdough, lactic acid, and the slightest hint of yeasty phenols.

When tasting the beer, I picked up the fruit flavors first. These were a mixture of tart cherry pie and cherry jam. The beer’s souring was an almost equal mix of lactic acid from the lambic and malic / citric acids from the cherries. The souring came across as soft and refreshing while the acidity level made the fruit taste bright and lively. Although the beer was very dry, it’s tannins, both from the grains and cherry skins, boosted the body and made the beer feel fuller in my mouth. The house lambic character, which makes Cantillon products so sought after, was layered directly underneath the fruit flavors. While difficult to describe, this “funk” was a combination of complexity and softness. I’ll refer to the Brettanomyces aroma / flavor wheel to try to characterize these Brett qualities. The blend that Jean Van Roy produces has attributes from the floral, woody, earthy, animal, savory, and fruity categories without presenting any flavors that I could detect from the solvent, putrid, chemical, or spicy categories.

When tasting the beer, I picked up the fruit flavors first. These were a mixture of tart cherry pie and cherry jam. The beer’s souring was an almost equal mix of lactic acid from the lambic and malic / citric acids from the cherries. The souring came across as soft and refreshing while the acidity level made the fruit taste bright and lively. Although the beer was very dry, it’s tannins, both from the grains and cherry skins, boosted the body and made the beer feel fuller in my mouth. The house lambic character, which makes Cantillon products so sought after, was layered directly underneath the fruit flavors. While difficult to describe, this “funk” was a combination of complexity and softness. I’ll refer to the Brettanomyces aroma / flavor wheel to try to characterize these Brett qualities. The blend that Jean Van Roy produces has attributes from the floral, woody, earthy, animal, savory, and fruity categories without presenting any flavors that I could detect from the solvent, putrid, chemical, or spicy categories.

The characteristic flavor of almonds, extracted from the cherry pits, was moderately present and added to the beer’s complexity along with a light touch of hop cheesiness. The high carbonation level kept the beer spritzy and lively while drinking. Every sip embodied a progression from bright sour fruit, to a complex leathery and earthy middle, to a nice dry finish that was refreshing and left me salivating for more.

The best way that I can describe the experience of drinking a Cantillon Kriek is to say that it’s acidity and perceived fruit sweetness balance each other in a way that promote the best flavors of each without either being over-the-top. When these krieks are young, less than a year in the bottle, the cherry flavors easily overpower the funk. At about the two-year mark, the age of this recent bottle, the Brett character kicks up significantly, and in my experience becomes balanced in intensity with the fruit flavors. Older bottles will show a diminished, less juicy, and more wine-like cherry character with intense levels of funk. I find each age to be delicious, but probably enjoy the balance of two-year old vintages the most.

Over the years, I have been fortunate enough to drink a number of fantastic Belgian lambics, American sour beers, and funky farmhouse ales. With all of these great drinking experiences I have never had a “favorite” beer. That being said, I have come back time and time again to enjoy Cantillon Kriek. It is simply a world-class beer and one that I always keep stocked in my cellar. With demand for excellent traditional examples of lambic beers on the rise world-wide, it is often difficult to find Cantillon Kriek and it is often quite expensive when you do find a bottle. However, if you’re a fan of sour beer and have never had a chance to taste this one, you owe it to yourself to seek it out. Hopefully, knowing a little bit more about the origins of the style and artistry that goes into its blending will make it all the more delicious!

Over the years, I have been fortunate enough to drink a number of fantastic Belgian lambics, American sour beers, and funky farmhouse ales. With all of these great drinking experiences I have never had a “favorite” beer. That being said, I have come back time and time again to enjoy Cantillon Kriek. It is simply a world-class beer and one that I always keep stocked in my cellar. With demand for excellent traditional examples of lambic beers on the rise world-wide, it is often difficult to find Cantillon Kriek and it is often quite expensive when you do find a bottle. However, if you’re a fan of sour beer and have never had a chance to taste this one, you owe it to yourself to seek it out. Hopefully, knowing a little bit more about the origins of the style and artistry that goes into its blending will make it all the more delicious!

Cheers!

Matt “Dr. Lambic” Miller

References:

Guinard, Jean-Xavier. Lambic. Boulder, CO, USA: Brewers Publications, 1990. Print.

“Kriek 100% Lambic.” Cantillon Brewery. Cantillon, n.d. Web. 24 Jan. 2015. <http://cantillon.be/br/3_102>.

Sharp, M. “Brasserie Cantillon”, Lambic Digest #603, 14 May 1995.

Steen, Jef Van Den. Geuze & Kriek: The Secret of Lambic. Tielt, Belgium: Lannoo, 2011. Print.