Hello Sour Beer Friends!

Today we get to talk about something that doesn’t usually play a significant role in sour beers… Hops! While hops are a critical component in the recipes for a vast majority of both the classic beer styles and styles developing in the American craft beer scene, they typically take a back seat in the formulation of sour beers. This is the case because when hops are utilized in the boiling process the bitterness they add can clash with the acidity developed in a sour beer.

Today we get to talk about something that doesn’t usually play a significant role in sour beers… Hops! While hops are a critical component in the recipes for a vast majority of both the classic beer styles and styles developing in the American craft beer scene, they typically take a back seat in the formulation of sour beers. This is the case because when hops are utilized in the boiling process the bitterness they add can clash with the acidity developed in a sour beer.

In fact, when thinking about how ingredients in a food or drink recipe are utilized, one typically uses either sour flavors or bitter flavors to balance sweetness. In beer, the malt or other cereal grains provide sweetness in the form of both fermentable and non-fermentable sugars (often referred to as a beer’s “malt backbone”). When hops are boiled they produce bitter alpha-acids which then balance this sweetness. Without something to balance the malt, even light bodied beers would taste cloyingly sweet as well as bland and one-dimensional. Contrasting hop-bittered beers, sour beers utilize organic acids produced during the fermentation to balance malt sweetness. In this way, the flavor profile of many sour beers share commonalities with wine, in which natural acidity from the grapes balances both residual sugar sweetness and perceived ester sweetness also from the grapes.

There are examples of beers in which a combination of bitterness and souring do taste good together, but these tend to be the exception rather than the rule. Gueuze, a style blended from lambics of differing ages, comes to mind. Some very good gueuzes can actually be slightly bitter in addition to being sour. Keep in mind that this is relative to no bitterness whatsoever. These gueuzes may contain on average as many as 10 to 20 IBU’s (International Bitterness Units, a way of measuring alpha-acid in a beer). When compared to styles like American Pale Ale (30-45 IBUs) or India Pale Ale (40-70 IBUs), we see that these sours are still significantly less bitter than many common types of craft beer.

Barrel aged stock ales which have been left to sour are another style of beer that can combine bitterness and souring in a pleasant way. A very nice example of one would be Bitter and Twisted Zymatore by Harviestoun Brewery. This is an English IPA that has been aged and allowed to sour in the barrel. Historically, all barrel stored (stock) British ales would have developed some level of souring and/or Brettanomyces character as they aged. These soured or funkified ales would sometimes be blended into young fresh beers to add flavor complexity and product consistency. I should note that the reason these soured stock ales tend to be pleasant is because while aging their bitterness level does decrease as their sour character increases. Don’t expect to find a sour version of an 80 IBU American Double IPA that tastes like anything but a train-wreck.

Barrel aged stock ales which have been left to sour are another style of beer that can combine bitterness and souring in a pleasant way. A very nice example of one would be Bitter and Twisted Zymatore by Harviestoun Brewery. This is an English IPA that has been aged and allowed to sour in the barrel. Historically, all barrel stored (stock) British ales would have developed some level of souring and/or Brettanomyces character as they aged. These soured or funkified ales would sometimes be blended into young fresh beers to add flavor complexity and product consistency. I should note that the reason these soured stock ales tend to be pleasant is because while aging their bitterness level does decrease as their sour character increases. Don’t expect to find a sour version of an 80 IBU American Double IPA that tastes like anything but a train-wreck.

But when it comes to the hop’s role in beer, bitterness isn’t the end of the story… Enter the realm of hop flavor and aroma. Essential hop oils, the component of hops that add flavor and aroma but not bitterness, are highly volatile substances. When hops are added to boiling wort, these flavor and aroma components are extracted, but then evaporate out of the mixture rather quickly. Brewers combat this effect by adding these “character” hops late in the boil, thus extracting oils but not boiling long enough to drive them away. Another method brewers use to add hop aroma to a beer without contributing bitterness is called “dry hopping”. Dry hopping involves the addition of hops into a beer after it has finished fermenting and it is this practice which has huge potential in the realm of sour beer production.

While still fairly uncommon, dry-hopped sour beers are awesome! They combine delicious sour beer flavors with the floral, herbal, piney, and/or citrus aromas and flavors of hops. These hop additions often enhance certain characteristics produced by Brettanomyces fermentations, like earthy aromas, wet hay and grass, or flavors of mango, pineapple, and other tropical fruits.

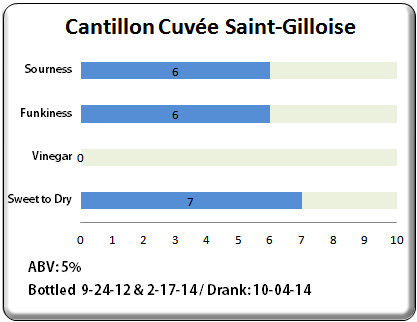

Recently, I drank two vintages of Cantillon’s Cuvée Saint-Gilloise (2012 & 2014) with a group of friends including two authors for this site, Cale Baker and Carlo Palumbo. Cuvée Saint-Gilloise (CSG) is a specialty gueuze produced from a blend of two-year-old lambic which is then dry hopped for 3 weeks in casks with Hallertau hops and bottle conditioned using Belgian candi sugar. I first tried CSG several years ago and it was my first introduction to dry-hopped sours. It is an excellent example of the style and well worth seeking out.

CSG pours slightly hazy with a golden straw color typical of Cantillon gueuzes. The 2012 vintage had less hop aroma overall and smelled lemony with a slightly cheesy / waxy character. The 2014 vintage was much brighter in hop aroma, with lots of noble hop character being apparent. Notes of tropical fruit, cantaloupe, honey, and floral fabric softener were all present.

CSG pours slightly hazy with a golden straw color typical of Cantillon gueuzes. The 2012 vintage had less hop aroma overall and smelled lemony with a slightly cheesy / waxy character. The 2014 vintage was much brighter in hop aroma, with lots of noble hop character being apparent. Notes of tropical fruit, cantaloupe, honey, and floral fabric softener were all present.

When tasting these two vintages, the 2014 bottle stood out to the group as distinctly better. Some of the flavor complexity and fresh hop notes are lost to more aggressive Brettanomyces funk as the beer ages. I would definitely recommend drinking this beer relatively fresh. The 2014 CSG tasted lemony, with flavors of white peaches, green tea, and herbal notes from the Hallertau hops. The souring of both vintages was fairly equivalent and moderate, about the tartness of unsweetened lemonade. The 2012 vintage was more astringent and assertively funkier, with sharper grass-like notes. There was still hop character present in the older version, but it had begun to take on a somewhat cheesy / papery note. I will point out that in these comparisons, the 2012 CSG was still a delicious beer, however the 2014 version was world-class. Amazingly, for spontaneously fermented products, the flavor intensity of souring, overall Brettanomyces character, vinegar content, and dryness were all identical between the two vintages. This is a testament to Jean Van Roy’s palate and blending skills.

There has never been a more exciting time in the world of sour beer. Brewers are not only beginning to experiment with these beers, but many are consistently producing excellent or even world-class examples. Hops have been a key flavor component in so many of the greatest examples of American and European craft beers that it only makes sense to see creative brewers and blenders utilizing hops in their sour-beer projects as well.

If you get a chance to try Cantillon Cuvée Saint-Gilloise, definitely take the opportunity to do so. Additionally, check out our list of other excellent dry-hopped sour beers! And if you know of a hoppy sour that I didn’t list, please comment on the article and recommend it to our readers.

Cheers!

Matt