Hello Sour Beer Friends!

Over the past two years, the popularity of craft brewed American sour beers has skyrocketed and a plethora of new sours have been introduced to the market. The fact that a high percentage of these have been of the fast / kettle soured variety has led me to write quite a bit geared toward the quality production of fast soured beers. Feeling that I have achieved my goal of providing thorough guidance regarding these beers, I would like to turn my attention throughout 2016 toward my first passion: aged and blended sours. In my opinion, many of the best sour beers in the world are crafted by brewers with aging and blending programs. This article will focus specifically on blending, which is undoubtedly one of the most powerful and versatile tools within the sour brewer’s toolkit.

Through this article, I will discuss blending from both a conceptual and practical standpoint. We will cover blending theory and the chemistry behind many common sour beer flavors, how to plan a blending session, ways to evaluate the beers being blended, and key goals for the blending of a variety of sour beer styles. I will also include real world examples using the tasting and blending notes from my own blending program. My goal is to make this information equally useful to both homebrewers and commercial craft brewers starting their own sour beer programs. Let’s get started with a discussion of why blending is such a versatile tool, looking at both what it can and cannot do for us as brewers.

An Introduction to Blending

As a craft brewing tool, blending can serve a number of purposes. Broadly speaking, I would divide the blending of beers into two general categories: practical and artistic. Of the two, practical blending is typically more straightforward with a functional goal in mind. For example, If a brewer wants to add a specialty flavor to a beer, such as vanilla to a porter, one way to achieve the desired level of this flavor would be to divide the batch in half, add vanilla to only one of the batches, then experiment with blending to find the proportion of each that creates the optimum level of vanilla flavor for that beer. Another example of practical blending would be the use of one beer to adjust a desired characteristic in another. Let’s say that a brewer accidentally mashes a west coast style IPA too high and the resulting beer doesn’t attenuate to the desired level… This brewer could create a second batch that is both mashed lower and utilizes a higher percentage of simple sugar resulting in a very dry and light bodied version of the same beer. Through blending, these two batches could be combined to create an IPA with the body and dryness originally intended by the brewer.

On the other end of the spectrum, the goal of artistic blending is to use a number of individual batches of beer like building blocks to create a final blend that embodies a complexity of aroma and flavor unattainable by a single fermentation. Artistic blending marries perfectly with, and indeed developed historically from, the practice of aging beer in wooden barrels. Whether these beers are spontaneously inoculated or more scientifically fermented, the act of aging in relatively small individual vessels will inevitably create differences and varying qualities in each batch of beer. The true art of blending has traditionally been exemplified by the master lambic blenders of Belgium. However, over the past two decades, a number of craft breweries in the United States have developed substantial barrel programs and utilize artistic blending to craft a wide variety of world class sour beers.

To the homebrewer or startup craft brewer, the blending of delicious and complex sours which rival world class examples may seem to be an impossible feat. In fact, while there are definitely challenges to overcome, it is certainly possible through planning, training, and most importantly, maintaining a dedication to only use beers that are free of defects in the blending process. Artistic blending is a method used to create synergy and elevate a beer to its highest quality. It should never be used to attempt to cover up an off-flavor or defect in a beer. The fact that many world class sour beers embrace some seriously funky characteristics does not mean that the sky is the limit. I will give examples of flavors that, while off-putting in high concentrations, can make positive contributions to a blend and I will cover flavors that should never be included in a blend a bit later. For now, if there is one pearl of wisdom I would impart on every new sour brewer it would be this: Strike the idea of “blending out” an undesirable flavor from your world view!

Getting Into The Blending Mindset

As brewers, we often think of brewing as a linear process that starts on the “hot side” with wort production and then follows a specific set of cold side fermentation and conditioning steps until the beer is ready to be packaged and served. As sour brewers and blenders we are forced to step back from this linear approach and accept a greater level of unpredictability. Personally, I think of a sour beer aging and blending program much like I think of a garden, with the resulting beers being like various salads produced from that garden.

Like tilling and planting a garden, a sour beer program will require a great deal of upfront work in terms of wort production. Once this wort has been introduced into the program, it will largely be up to nature to determine when the individual blender beers within the program become “ripe”. This isn’t to say that you should sit back and ignore your sour beer aging program. Like a garden, it will require routine tending and maintenance to keep the beers within it in the best possible health. The average gardner doesn’t want to eat only one type of vegetable for every meal, and likewise, most brewers will want to build variety into their aging programs. Most importantly, if a gardener wants a fresh and delicious salad, they will go out and make it from the ripest fruits and vegetables, whatever they may be at that time. A sour blender should tend to and monitor their aging beers, allowing the program itself to tell them when a sufficient number of beers have become ready to use in a blend. Like a fresh garden salad, a finished sour beer will never be exactly the same twice, but should be the best possible beer that your program can produce at any given time. Finally, and I will keep harping on this because it is important, you wouldn’t put together a fantastic fresh salad and then throw in some rotten tomatoes just because you had them available. Don’t make the same mistake with your beer.

Like tilling and planting a garden, a sour beer program will require a great deal of upfront work in terms of wort production. Once this wort has been introduced into the program, it will largely be up to nature to determine when the individual blender beers within the program become “ripe”. This isn’t to say that you should sit back and ignore your sour beer aging program. Like a garden, it will require routine tending and maintenance to keep the beers within it in the best possible health. The average gardner doesn’t want to eat only one type of vegetable for every meal, and likewise, most brewers will want to build variety into their aging programs. Most importantly, if a gardener wants a fresh and delicious salad, they will go out and make it from the ripest fruits and vegetables, whatever they may be at that time. A sour blender should tend to and monitor their aging beers, allowing the program itself to tell them when a sufficient number of beers have become ready to use in a blend. Like a fresh garden salad, a finished sour beer will never be exactly the same twice, but should be the best possible beer that your program can produce at any given time. Finally, and I will keep harping on this because it is important, you wouldn’t put together a fantastic fresh salad and then throw in some rotten tomatoes just because you had them available. Don’t make the same mistake with your beer.

In order to keep this article on topic, we are going to stay focused on the actual blending portion of sour beer creation. In the future, I will introduce articles that discuss further topics important to a well rounded sour beer program such as wort production, spontaneous vs. controlled fermentation, avoiding problems during aging through proper barrel & barrel room maintenance, etc. At this point we are going to assume that you’ve got a variety of mature blender beers that are ready to be used to craft one or more final products. The next step will to be to plan your blending day. Throughout the rest of this article, I will discuss blending concepts and methods using “barrels” when referencing individual blender beers. This should not be a discouragement to homebrewers, as all of these concepts are equally applicable to beers being aged in carboys or any variety of aging vessels.

Planning a Blending Session

When it comes to artistically blending sour beers, a brewer’s most important tools are their palate and, hopefully, the palates of a small group of beer tasters that will help to error check and confirm the findings of the head blender. There are two things a blender can do in order to ensure that their palate is on-point during a blending session: training before blending day and creating an ideal set of conditions for tasting on blending day.

Palate Training

In terms of sour beer blending, I think that palate training can be broken into two deceptively simple categories: developing a taste for characteristics that you would want to include or adjust in any given blend, and identifying off-flavors that would prevent a beer from being used in a blend. The first category, tasting positive qualities in a beer, is a skill which not only takes time to develop but will also require a serious sour brewer and blender to seek out and experience a wide variety of sample beers.

For example: Let’s say that you would like to blend a beer that will be used to create a raspberry sour inspired by a traditional Oude Lambic Framboise. You’ve done your homework and put the necessary starting ingredients into your aging program by designing beers with a malt bill similar to traditional lambics. You’ve also started those beer’s fermentations either spontaneously or with a variety of mixed cultures that contain organisms isolated from traditional lambics. Now you will be waiting for up to several years for your blender beers to mature. What do you do in the meantime? My answer: Get your hands on every example of traditional framboise and gueuze that you can find. In my opinion, doing so is the only way to truly understand any style, especially one as complex as a fruit lambic. Furthermore, you will begin to build a palate memory for the wide variety of flavors and aromas that occur in such beers. Having these memories will allow you to identify blender beers in your own program that share these characteristics.

For example: Let’s say that you would like to blend a beer that will be used to create a raspberry sour inspired by a traditional Oude Lambic Framboise. You’ve done your homework and put the necessary starting ingredients into your aging program by designing beers with a malt bill similar to traditional lambics. You’ve also started those beer’s fermentations either spontaneously or with a variety of mixed cultures that contain organisms isolated from traditional lambics. Now you will be waiting for up to several years for your blender beers to mature. What do you do in the meantime? My answer: Get your hands on every example of traditional framboise and gueuze that you can find. In my opinion, doing so is the only way to truly understand any style, especially one as complex as a fruit lambic. Furthermore, you will begin to build a palate memory for the wide variety of flavors and aromas that occur in such beers. Having these memories will allow you to identify blender beers in your own program that share these characteristics.

When tasting a beer with palate training in mind, I would recommend doing so in a relaxed environment that is free of distractions. It is helpful to serve a beer in clean glassware at the appropriate temperature for the style and then taste it slowly over a period of time so that by the final tastes the beer is approaching room temperature. As the temperature rises, the mix of aromas and flavors that are apparent can change dramatically. It helps to take notes on what you are perceiving and, if you are with company, discuss your findings. Even if you never re-read the notes, the action of both writing and speaking directly activates those two centers in the brain and this can help to develop a more permanent form of memory. When tasting beer in this sense, I find it helpful to take notes on the following:

- What distinct aromas do you perceive and how can you relate them to other things you have smelled?

- What unique flavors do you perceive and where have you tasted them before?

- How is the beer balanced? Does the acidity dominate the malt, vice versa, or are they equally present?

- Are there bitter components that may arise from hops or some other ingredient? How does the bitterness compare in intensity to the malt presence and acidity?

- Is there a sense of tannic astringency? Do you pick it up at the beginning, middle, or end of a taste? Does it remind you of red wine, dry white wine, or underripe fruit?

- Do you taste any off-flavors or flavors that you find unpleasant or distracting?

- Can you taste the presence of alcohol? Does its presence correlate with what you know the ABV to be?

- How does the beer’s mouthfeel rank from thin to full-bodied? What is the carbonation level from still to champagne-like?

- Does a particular characteristic of this beer exactly match your memory of another beer?

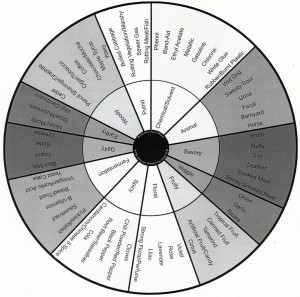

The Brettanomyces Flavor Wheel is a great reference to have available when tasting sour beers for the purpose of palate training.

Aside from preparing you to become a contributing author for Sour Beer Blog, creating a set of notes like this will force you to think specifically about all of these different attributes for each beer that you’re tasting. Over time, you will build and hone your palate memory which will directly improve your blending skills.

The second half of palate training is learning to identify off-flavors when you taste them. From a quality management perspective, this is potentially even more important than identifying the flavor-positive attributes of a beer. As a beginning blender, if you learn to exclude any beer that contains off-flavors from a blend, your resulting beers will, at a minimum, be off to a good start. From that point it just takes experience and finesse to make them great. I think that one of the easiest ways to learn about off-flavors is to form a tasting group. Members of the group can be asked to find beers that contain a particular off-flavor to share. As a blender, these group tastings will be important to help you identify any “blind-spots” in your palate. Everyone potentially has these, so it is important for you to be honest with yourself about what you can and cannot taste. If you identify that you have a particular blind-spot then it will allow you to recruit people to help you on blending day to check for that particular flavor and avoid it in your choices. The following flavors and aromas are of particular relevance to sour beer blending and should be the first things you learn to identify:

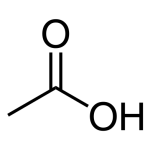

Acetic Acid – The same chemical as vinegar, acetic acid CAN be included at low levels into a blend but should be done so with caution. At low levels this acid helps to round out lactic acid to create a fuller, more complex type of sourness common to lambic style beers. If there is a distinct malt vinegar flavor in a beer then this is too much acetic acid. Additionally, if a sour beer tastes harsh, or actually burns the throat, this is typically a sign of too much acetic acid. During aging, Brettanomyces can convert acetic acid into ethyl acetate, so use extreme caution with blenders that show evidence of both. With age, a beer that has acceptable levels of both acetic acid and ethyl acetate can evolve to have an unacceptable level of ethyl acetate.

Acetic Acid – The same chemical as vinegar, acetic acid CAN be included at low levels into a blend but should be done so with caution. At low levels this acid helps to round out lactic acid to create a fuller, more complex type of sourness common to lambic style beers. If there is a distinct malt vinegar flavor in a beer then this is too much acetic acid. Additionally, if a sour beer tastes harsh, or actually burns the throat, this is typically a sign of too much acetic acid. During aging, Brettanomyces can convert acetic acid into ethyl acetate, so use extreme caution with blenders that show evidence of both. With age, a beer that has acceptable levels of both acetic acid and ethyl acetate can evolve to have an unacceptable level of ethyl acetate.

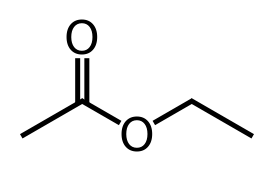

Ethyl Acetate – This chemical exists at some low level in all traditional lambics and most sour beers that contain Brettanomyces, so the concept of eliminating it completely isn’t realistic. At low levels, ethyl acetate will add a fruity pear-like note to the aroma of a beer. At intermediate levels, this chemical sharpens the acidity of a sour beer. At a certain threshold, which will vary for each individual, this assertiveness transforms into solvent-like harshness. To most tasters, too much ethyl acetate will come through like nail polish remover or acetone. For the home improvement or construction folks, I think ethyl acetate smells exactly like uncured silicone caulk. For beginning blenders, if you can distinctly detect ethyl acetate in a beer, I would recommend against using that beer in a blend.

Ethyl Acetate – This chemical exists at some low level in all traditional lambics and most sour beers that contain Brettanomyces, so the concept of eliminating it completely isn’t realistic. At low levels, ethyl acetate will add a fruity pear-like note to the aroma of a beer. At intermediate levels, this chemical sharpens the acidity of a sour beer. At a certain threshold, which will vary for each individual, this assertiveness transforms into solvent-like harshness. To most tasters, too much ethyl acetate will come through like nail polish remover or acetone. For the home improvement or construction folks, I think ethyl acetate smells exactly like uncured silicone caulk. For beginning blenders, if you can distinctly detect ethyl acetate in a beer, I would recommend against using that beer in a blend.

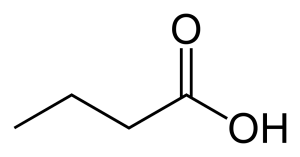

Butyric Acid – This organic acid is known to be produced by the Clostridium family of bacteria but may potentially also arise from groups of bacteria which have not been thoroughly studied in relation to brewing science. Butyric acid has a noxious, vomit-like aroma and a flavor associated with rancid butter and bile. The most common source of this chemical in sour beer is from contamination during sour mashing or kettle souring techniques. It can also develop during traditional mixed culture or spontaneous fermentation in situations where the wort goes through a long phase without active fermentation. If these aromas or flavors are present in any detectable level in a blender beer, it should not be used in a blend. If the butyric acid level is low, such beers can be inoculated with an active and healthy pitch of Brettanomyces and aged further. In cases with higher levels of contamination, these beers may never recover and should be discarded.

Butyric Acid – This organic acid is known to be produced by the Clostridium family of bacteria but may potentially also arise from groups of bacteria which have not been thoroughly studied in relation to brewing science. Butyric acid has a noxious, vomit-like aroma and a flavor associated with rancid butter and bile. The most common source of this chemical in sour beer is from contamination during sour mashing or kettle souring techniques. It can also develop during traditional mixed culture or spontaneous fermentation in situations where the wort goes through a long phase without active fermentation. If these aromas or flavors are present in any detectable level in a blender beer, it should not be used in a blend. If the butyric acid level is low, such beers can be inoculated with an active and healthy pitch of Brettanomyces and aged further. In cases with higher levels of contamination, these beers may never recover and should be discarded.

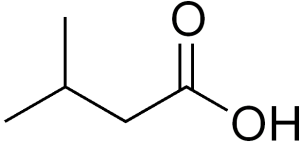

Isovaleric Acid – Isovaleric acid has two potential sources in sour beer: from unwanted microbial growth or from the use of aged hops. In high concentrations, this organic acid can be difficult to distinguish from butyric acid and is equally offensive. At intermediate levels, isovaleric acid smells of strong cheese or foot odor. At very low levels, this acid takes on the funky odor of bleu cheese and can be incorporated into blends if this level of funk is desired. These acceptable (very low) levels of isovaleric acid only arise in blender beers from the use of aged hops such as are used in the traditional lambic brewing process. If a sour mashed or kettle soured beer portrays characteristics of isovaleric acid, this beer should not be used in a blend. Isovaleric acid that arises from microbial sources is almost universally of too high a concentration to be incorporated into a quality blend. Furthermore, these blender beers do not improve with age. Use blender beers that portray aged hop cheesiness with appropriate caution and when in question.. DUMP THEM!

Isovaleric Acid – Isovaleric acid has two potential sources in sour beer: from unwanted microbial growth or from the use of aged hops. In high concentrations, this organic acid can be difficult to distinguish from butyric acid and is equally offensive. At intermediate levels, isovaleric acid smells of strong cheese or foot odor. At very low levels, this acid takes on the funky odor of bleu cheese and can be incorporated into blends if this level of funk is desired. These acceptable (very low) levels of isovaleric acid only arise in blender beers from the use of aged hops such as are used in the traditional lambic brewing process. If a sour mashed or kettle soured beer portrays characteristics of isovaleric acid, this beer should not be used in a blend. Isovaleric acid that arises from microbial sources is almost universally of too high a concentration to be incorporated into a quality blend. Furthermore, these blender beers do not improve with age. Use blender beers that portray aged hop cheesiness with appropriate caution and when in question.. DUMP THEM!

- Oxidation – All beer aged in barrels and most beers aged in any manner will experience some level of micro-oxygenation. This low and slow oxygen exposure can have a variety of beneficial effects on sour beer and it is due to this that quality oak barrels are highly valued by sour beer producers. Sour beer with positive effects from oxidation may develop sherry notes, fruity notes, and / or complex caramel or melanoidin characteristics. Even some of the less desirable effects of oxidation such as a mild paper / cardboard flavor can add to the complexity of funkier sour beers such as traditional lambics. However, caution must be used when incorporating any beer that shows strong signs of oxidation into a blend. Strong oxidation can show itself in sour beer as aromas and flavors of sawdust, rotten fruit, cheese, or wet dog. These characteristics are the result of the end point of malt and hop oxidation compounds and they do not belong in properly blended sour beers.

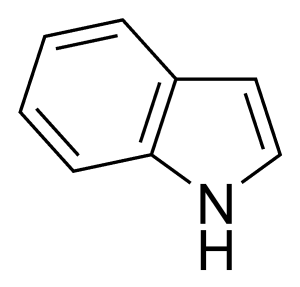

Indole – Indole is a compound produced microbially from the metabolism of the amino acid tryptophan. Present in human feces, Indole is the chemical responsible for the fecal, “baby diaper”, or manure aromas present in some sour beers. Indole is often a transient chemical during the lifetime of a sour beer. Its concentration can both rise and fall depending upon the specific mix of microorganisms metabolizing at any given time. I would recommend against the use of any blender beer with a notable fecal aroma when crafting a blend. Alternatively, these beers should be allowed to continue to age and rechecked at a later date to see if this aroma has subsided. Advanced blenders may incorporate low levels of indole containing beers into funkier blends to emulate certain lambic varieties, but again, I recommend doing so with extreme caution. Most drinkers will be put off by any level of poop smell in their beer.

Indole – Indole is a compound produced microbially from the metabolism of the amino acid tryptophan. Present in human feces, Indole is the chemical responsible for the fecal, “baby diaper”, or manure aromas present in some sour beers. Indole is often a transient chemical during the lifetime of a sour beer. Its concentration can both rise and fall depending upon the specific mix of microorganisms metabolizing at any given time. I would recommend against the use of any blender beer with a notable fecal aroma when crafting a blend. Alternatively, these beers should be allowed to continue to age and rechecked at a later date to see if this aroma has subsided. Advanced blenders may incorporate low levels of indole containing beers into funkier blends to emulate certain lambic varieties, but again, I recommend doing so with extreme caution. Most drinkers will be put off by any level of poop smell in their beer.

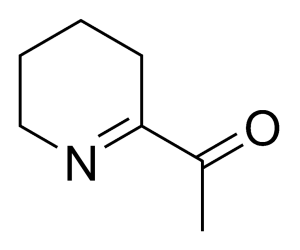

Tetrahydropyridines – Tetrahydropyridines are compounds produced during the metabolism of the amino acid lysine. With several known forms, this class of compounds can be both produced and broken down by all of the common classes of sour beer fermenters including Brettanomyces, Lactobacillus, and Pediococcus. Considered to be an off-flavor producing set of chemicals in sour beer, tetrahydropyridines are responsible for a classic cheerios flavor which can arise in sour beer after kegging or bottling. Other flavors associated with Tetrahydropyridines include mousy, urine, or tortilla chip flavors. Like the other transient compound indole, some degree of these flavors may be present in funkier traditional lambic blends. Therefore, beers that portray these characteristics, like beers containing indole, can potentially be used during blending, but caution should be used and, ultimately, it would be best to continue to age and monitor these beers until these characteristics disappear.

Tetrahydropyridines – Tetrahydropyridines are compounds produced during the metabolism of the amino acid lysine. With several known forms, this class of compounds can be both produced and broken down by all of the common classes of sour beer fermenters including Brettanomyces, Lactobacillus, and Pediococcus. Considered to be an off-flavor producing set of chemicals in sour beer, tetrahydropyridines are responsible for a classic cheerios flavor which can arise in sour beer after kegging or bottling. Other flavors associated with Tetrahydropyridines include mousy, urine, or tortilla chip flavors. Like the other transient compound indole, some degree of these flavors may be present in funkier traditional lambic blends. Therefore, beers that portray these characteristics, like beers containing indole, can potentially be used during blending, but caution should be used and, ultimately, it would be best to continue to age and monitor these beers until these characteristics disappear.

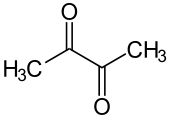

Diacetyl – Diacetyl is an intermediate compound produced during fermentation by all of the common families of sour beer fermenters including Saccharomyces, Brettanomyces, heterofermentative Lactobacillus, and (especially) Pediococcus. This chemical can be perceived to taste like the butter on movie theater popcorn or butterscotch. Diacetyl tends to be produced at higher levels during active fermentation and then will typically be reabsorbed by yeast species and metabolized into ethanol as the beer ages. Brettanomyces is especially good at reducing diacetyl and therefore it is always recommended to use Brettanomyces in beers being soured by Pediococcus due to this bacteria’s propensity to produce high levels of this off-flavor. In terms of blending, this is another example of a flavor that should be allowed more time to age out of beers before they are used.

Diacetyl – Diacetyl is an intermediate compound produced during fermentation by all of the common families of sour beer fermenters including Saccharomyces, Brettanomyces, heterofermentative Lactobacillus, and (especially) Pediococcus. This chemical can be perceived to taste like the butter on movie theater popcorn or butterscotch. Diacetyl tends to be produced at higher levels during active fermentation and then will typically be reabsorbed by yeast species and metabolized into ethanol as the beer ages. Brettanomyces is especially good at reducing diacetyl and therefore it is always recommended to use Brettanomyces in beers being soured by Pediococcus due to this bacteria’s propensity to produce high levels of this off-flavor. In terms of blending, this is another example of a flavor that should be allowed more time to age out of beers before they are used.

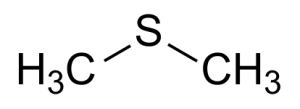

- Hydrogen Sulfide, Sulfites, & Mercaptans – These sulfur containing chemicals are all related to each other chemically and have overlapping flavor and aroma profiles which can vary from struck match, to rotten eggs, to rotten vegetables. Sulfur compounds such as these can be produced during the metabolism of the amino acids cysteine and methionine by both classic strains of brewer’s yeast as well a variety of bacterial species. Additionally, hydrogen sulfide can arise at above threshold levels from overuse of sulfur based antimicrobial compounds such as Camden tablets. In my experience, fermentations held at cooler temperatures tend to produce more sulfur aromas than those held at higher temperatures. This tendency is related to the rate of CO2 production during fermentation as vigorous bubbling of CO2 will help to scrub these volatile aroma compounds out of a beer. Following this train of thought, CO2 can often be manually bubbled through a beer to help remove unwanted aromas due to sulfur compounds. Additionally, these beers can be given longer aging times to reduce these compounds. Regardless of how sulfur issues are dealt with, beers that portray high levels of these aromas should not be included when blending. That being said, beers that contain VERY light sulfur aromas can be successfully used while blending to lend a funkier edge to certain styles and can even work synergistically with fruits that have a natural sulfur component such as peaches and apricots.

Dimethylsulfide (DMS) – DMS is another sulfur containing compound which produces a flavor reminiscent of cooked corn or the water that comes out of canned corn or other canned vegetables. If you are looking for a specific palate training example of this flavor, check out Rolling Rock Pale Lager, as this chemical is purposely retained within the beer to produce its signature flavor. DMS is not an off-flavor specific to sour beers but it can still occur within them. DMS is a volatile chemical produced from heating a component of malt called SMM (S-methyl-methionine). After its production, a vigorous boil will then drive-off the volatile DMS. As the boil progresses, the total amount of SMM present continues to lower until the risk of DMS becomes negligible. Very pale malts naturally contain more SMM than darker kilned malts and it is this fact that gives rise to the guideline to boil wort made from pale ale malts for 60 minutes or longer while worts made from pilsner malt should be boiled for 90 minutes or longer. Short or improperly vented boils are not the only potential source of DMS. This compound can also arise from a very slow and unhealthy fermentation or from certain beer spoiling microbes not common in sour beer fermentations. Regardless of its cause, if a blender beer contains detectable levels of DMS, it should not be used in a blend. Like other volatile sulfur compounds, low to intermediate levels of DMS can potentially be scrubbed out of a beer with CO2 bubbling, but if this does not work or is not feasible, then these beers should simply be dumped.

Dimethylsulfide (DMS) – DMS is another sulfur containing compound which produces a flavor reminiscent of cooked corn or the water that comes out of canned corn or other canned vegetables. If you are looking for a specific palate training example of this flavor, check out Rolling Rock Pale Lager, as this chemical is purposely retained within the beer to produce its signature flavor. DMS is not an off-flavor specific to sour beers but it can still occur within them. DMS is a volatile chemical produced from heating a component of malt called SMM (S-methyl-methionine). After its production, a vigorous boil will then drive-off the volatile DMS. As the boil progresses, the total amount of SMM present continues to lower until the risk of DMS becomes negligible. Very pale malts naturally contain more SMM than darker kilned malts and it is this fact that gives rise to the guideline to boil wort made from pale ale malts for 60 minutes or longer while worts made from pilsner malt should be boiled for 90 minutes or longer. Short or improperly vented boils are not the only potential source of DMS. This compound can also arise from a very slow and unhealthy fermentation or from certain beer spoiling microbes not common in sour beer fermentations. Regardless of its cause, if a blender beer contains detectable levels of DMS, it should not be used in a blend. Like other volatile sulfur compounds, low to intermediate levels of DMS can potentially be scrubbed out of a beer with CO2 bubbling, but if this does not work or is not feasible, then these beers should simply be dumped.

- Yeast Autolysis – As dead yeast cells break down within a beer they release a variety of chemical byproducts. This process can leave a beer with a rubbery, plastic, or rotten meat aroma and flavor. Sour beers with one or more active strains of Brettanomyces are often relatively resistant to the development of such off-flavors. This is because Brettanomyces will often metabolize the compounds being released from autolyzed yeast. However, this is not always the case depending upon both the strains involved and the quantity of yeast left to autolyze. The flavors of autolysis are sometimes mistaken by brewers to be part of the “good funk” present in complex sour blends but, in my opinion, this is a mistake. Beers that portray these characteristics should be avoided when blending.

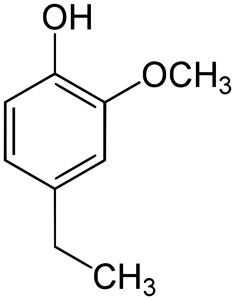

Phenolic Compounds – Phenolic compounds encompass a very large family of aroma and flavor producing chemicals that can exist within sour beer. Many of these compounds contribute to the enticing funkiness of traditional lambics and modern craft sours. There are, however, some aromas and flavors that may develop within properly brewed and fermented sour beers that are difficult to incorporate into a blend without overpowering it. Many of these chemicals will be perceived one way at low concentrations and differently as the concentration rises. For example, 4-ethyl phenol, which is commonly produced by Brettanomyces, produces a pleasant horsey, spicy, farmy funk at lower concentrations. However, as the concentration of this phenol rises, it can begin to taste like liquid smoke, Band-Aids, or Chloraseptic (medicinal). When creating a blend, flavors such as clove, pepper, baking spices (cinnamon, nutmeg, allspice), horse blanket, barnyard, hay, ozone, and dried flowers are all potentially positive additions to “good funk”. On the other hand, flavors such as plastic, smoky, bitter, burnt rubber, medicinal, or band-aid, should be avoided. The tricky part here is that the same phenolic compounds can create both sets of flavors. Therefore, if your blending beer portrays characteristics from the positive list, then it is okay to use this beer for any portion of the final blend. However, if a blending beer has flavors from the negative list, this beer may still potentially still be used as a small portion of the final blend. You have to be very careful with this type of blending, because without experimentation there will be no way to determine how much of one of these beers will be too much. To determine this, create a small scale version of your intended blend and then incorporate small and carefully measured volumes of your strongly phenolic beer into test glasses. Doing so will give you a guideline for how much of this strongly phenolic beer can be used to create a final blend with appropriate levels and varieties of funk. You may also find that the unpleasant phenolic flavors remain present regardless of the concentration that you try to incorporate. In these cases, the blender beer has a mix of phenols which can only produce negative flavors and this beer should be aged further or dumped.

Phenolic Compounds – Phenolic compounds encompass a very large family of aroma and flavor producing chemicals that can exist within sour beer. Many of these compounds contribute to the enticing funkiness of traditional lambics and modern craft sours. There are, however, some aromas and flavors that may develop within properly brewed and fermented sour beers that are difficult to incorporate into a blend without overpowering it. Many of these chemicals will be perceived one way at low concentrations and differently as the concentration rises. For example, 4-ethyl phenol, which is commonly produced by Brettanomyces, produces a pleasant horsey, spicy, farmy funk at lower concentrations. However, as the concentration of this phenol rises, it can begin to taste like liquid smoke, Band-Aids, or Chloraseptic (medicinal). When creating a blend, flavors such as clove, pepper, baking spices (cinnamon, nutmeg, allspice), horse blanket, barnyard, hay, ozone, and dried flowers are all potentially positive additions to “good funk”. On the other hand, flavors such as plastic, smoky, bitter, burnt rubber, medicinal, or band-aid, should be avoided. The tricky part here is that the same phenolic compounds can create both sets of flavors. Therefore, if your blending beer portrays characteristics from the positive list, then it is okay to use this beer for any portion of the final blend. However, if a blending beer has flavors from the negative list, this beer may still potentially still be used as a small portion of the final blend. You have to be very careful with this type of blending, because without experimentation there will be no way to determine how much of one of these beers will be too much. To determine this, create a small scale version of your intended blend and then incorporate small and carefully measured volumes of your strongly phenolic beer into test glasses. Doing so will give you a guideline for how much of this strongly phenolic beer can be used to create a final blend with appropriate levels and varieties of funk. You may also find that the unpleasant phenolic flavors remain present regardless of the concentration that you try to incorporate. In these cases, the blender beer has a mix of phenols which can only produce negative flavors and this beer should be aged further or dumped.

Now that we have discussed palate training from both a flavor positive and an off-flavor detection perspective, let’s take a look at what we can do on blending day to create the best set of conditions for tasting. Doing so will help us get the most out of our previous palate training.

Blending Day Do’s and Don’ts

Do:

Use glassware that concentrates aromas.

Use glassware that concentrates aromas.- Smell samples thoroughly before tasting.

- Allow a sample to hang out in your mouth for a few moments before swallowing. Breath some air into your mouth while tasting a sample, this unlocks potentially hidden flavors.

- Taste samples at a natural meal time when you are hungry. For most tasters, the ideal time will be between 11:00 am and 1:00 pm.

- Use palate cleansers such as water, light lager, unsalted crackers, or unseasoned breads.

- Taste samples in a calm and comfortable environment.

- Reset your sense of smell between samples by smelling the clean dry skin of your forearm for a few moments.

- Swallow a portion of each sample. Some palate senses are not activated when samples are spit out.

- Taste samples at cool or room temperature. When screening for off-flavors opt for warmer temperatures.

- Take notes on each sample.

Don’t:

- Smoke tobacco or marijuana immediately before or during the tasting.

- Wear perfume or cologne to the blending session.

- Drink samples ice cold.

- Eat salty, spicy, or greasy foods before or during the tasting.

- Taste samples while ill or upset.

- Get drunk.

Now that we are equipped with both palate training and practical tips for blending day, lets take a look at methods we can use to create our blended sour beer.

Blending Methods

When it comes to actually producing a blended sour beer, I am going to discuss two general methods as well as some variations and possibilities within those methods. None of these variations are inherently better than the others. They all focus on maintaining quality while having their own strengths and weaknesses depending upon the goal you are trying to achieve.

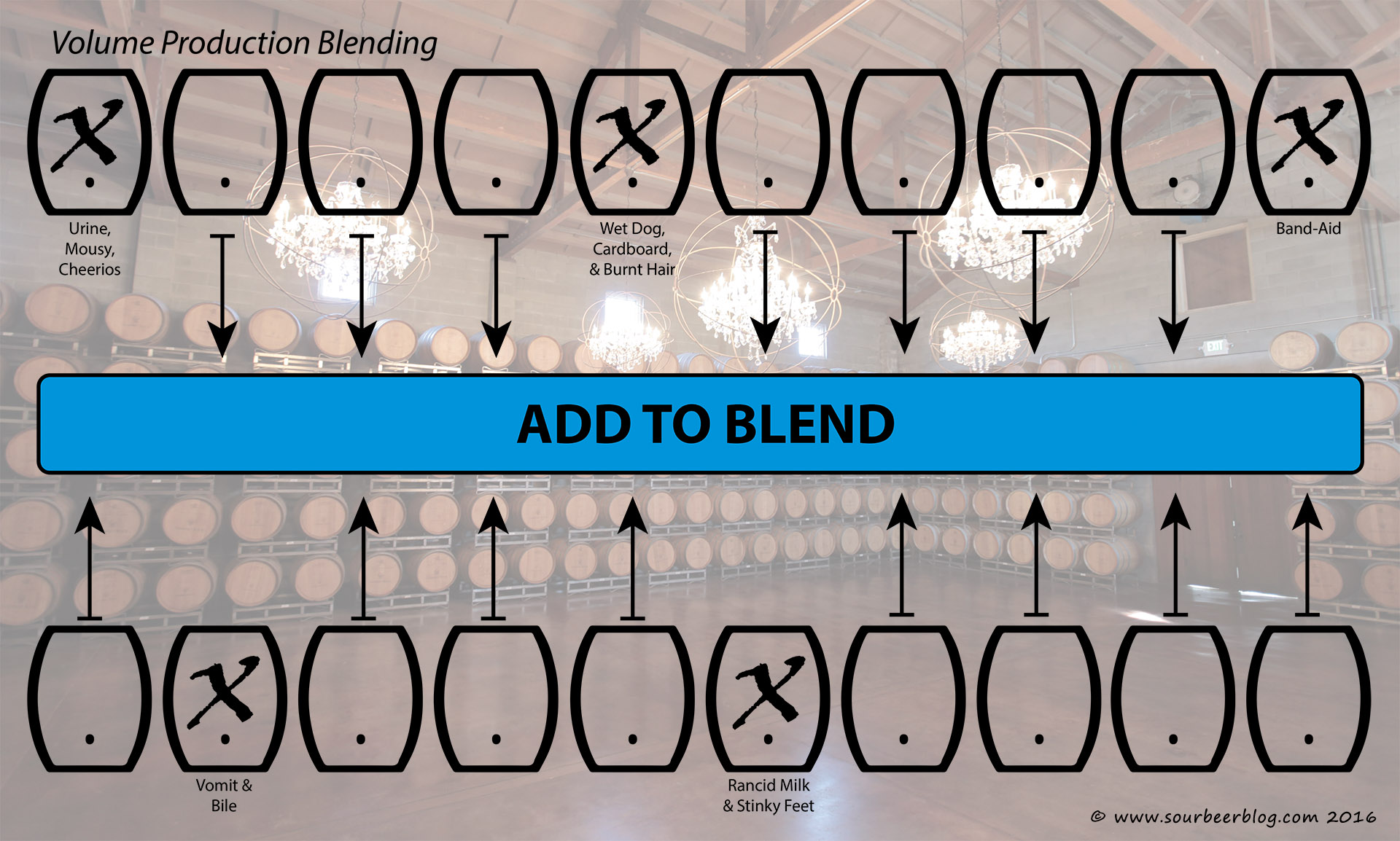

The first of these I will call the volume production method. This method tends to be the most applicable to sour brewers with large barrel programs who are looking to craft a particular blend on a rotating or seasonal basis. The simplest version of this method looks like this:

- The blender or group of blenders tastes samples of each barrel which could potentially be included in a blend (for example: all of the golden sour barrels with more than 6 months of age).

- Barrels that contain off-flavors that cannot be fixed with age (blend killers) are marked for disposal.

- Barrels with characteristics that fall too far from the profile of the intended final blend are excluded. Examples may include beers that are under-attenuated, too sour, not sour enough, have strong fermentation characteristics that don’t belong in this particular blend, etc. These may be allowed to age further, or used for other projects.

- After all the beers that shouldn’t be included have been marked, everything else is put into the blend.

In its simplest form, this style of blending is an effective way to produce a quality beer that portrays the “median” of the current range of flavors being produced within your aging program. It benefits from being relatively easy and straightforward to carry out. A drawback of this method is that the resulting blend may become somewhat muddled depending upon how many significantly different characteristics exist within all of the blender beers.

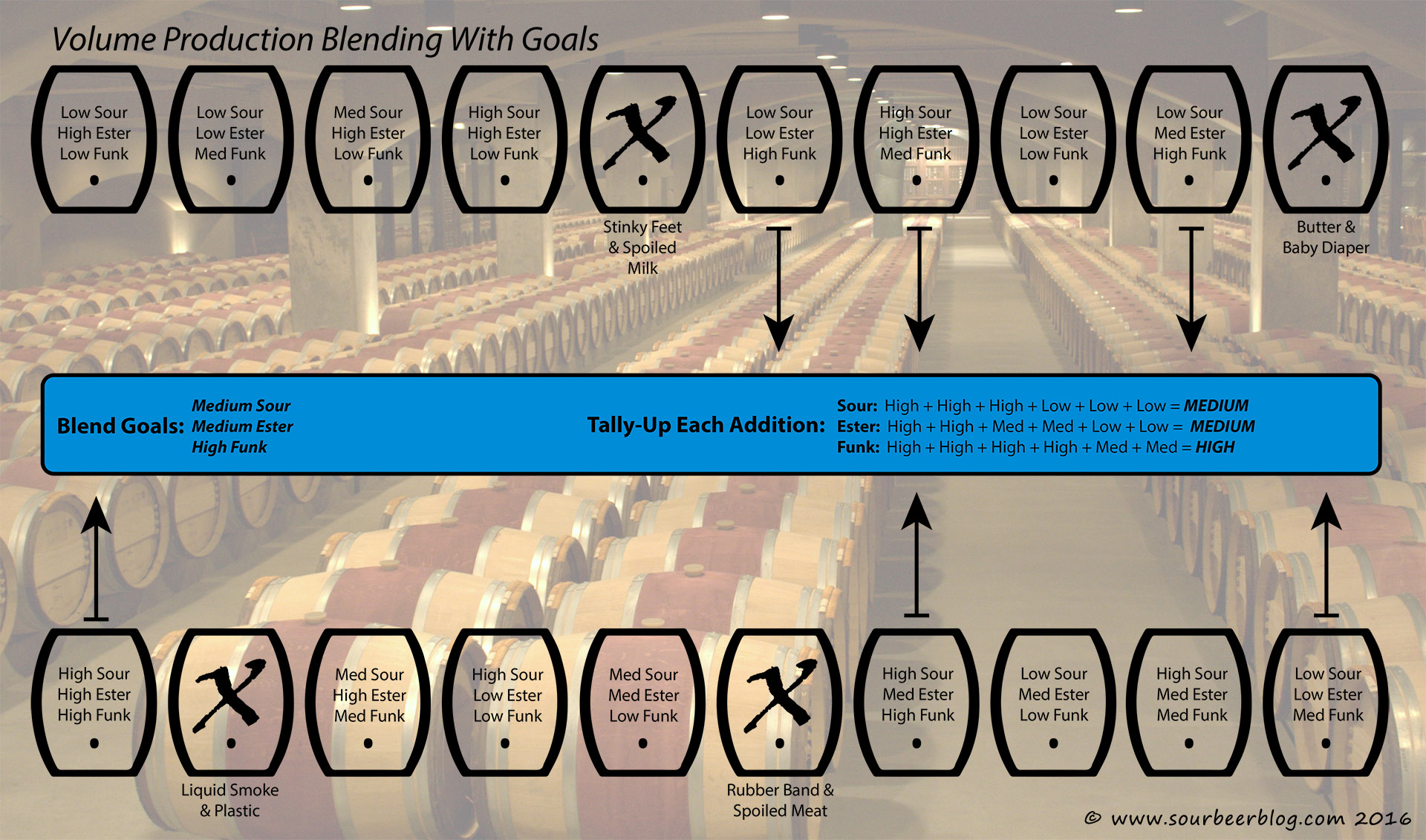

The next step-up in blending complexity takes the volume production method and adds some steps which will allow the brewer to steer the blend toward a more defined goal. To do this, add the following steps to the four steps discussed above:

- Before tasting any of the barrels, create a list of characteristics that you want to be able to control in the final blend. The more characteristics you choose, the more complicated the process will become. For example, if blending a Flanders style sour red ale, you may choose that you want to pay special attention to a beer’s sweet to dry balance, acidity, and fruit-like ester aromas.

- Create a basic scale for each attribute that you will take notes on when tasting. There is no right or wrong way to do this, it all comes down to your needs and what works for you. Using our Flanders red example, you could rank sweet to dry from 1 to 10, or you could simply mark beers as sweet, balanced, or dry. The more precision you build into your scale the more control you will have over your final blend but potentially the more complicated the planning process will become.

- After excluding any barrels that contain unwanted off-flavors, you will produce your final blend on paper by adding the characteristics of each barrel to a tally sheet. For example, let’s say that you want to create a Flanders Red with a balanced sweetness to dryness, moderate acidity and a medium to high level of fruit esters.

- Start by adding in all the barrels that contain beers that already match your desired characteristics.

- After that, begin adding in additional barrels one at a time and using other barrels to counterweight the characteristics that are different from your goal. For example, you may have 5 barrels that have exceptionally high ester qualities. However, three of these barrels are extremely acidic, and two are far too sweet / under-attenuated. You would seek to counteract these qualities by adding additional barrels that have low acidity yet are very dry.

- Continue this process until you have reached a desired blend volume or run out of blender beers with the necessary characteristics.

By tracking various characteristics and using them to plan the blend, you can really tailor this blending method to suit your needs and dial in your end product to whatever level of complexity and precision that is possible given the size and variety of your sour aging program. It benefits from giving you additional control over the final product, while a major drawback of this method is that is takes more time to plan the blend. Additionally, as your desire to dial-in an exact mental picture of a beer increases, the more beers you may have to exclude from the blend, and the smaller your final output will become.

I call the final style of blending that we will discuss the cuvée method. This process is essentially our previous methods taken to the maximum level of tasting, note taking, and planning. This method works best to produce a relatively small final blend from a relatively large aging program with a large level of variation and options within its beers. This style of blending is the most similar to that performed by traditional lambic blenders when producing specialty or “cuvée” blends. One a commercial scale, this type of blending typically starts as a secondary project that develops after tasting all of the barrels for a volume production blend. During this tasting, barrels with notable and distinct fermentation characteristics are marked for a more detailed tasting to be done at a later time. From this point, a cuvée blend looks like this:

- Beers are tasted by a blender or group of blenders and a full set of tasting notes is recorded for each beer in consideration. Special attention is paid to unique fermentation characteristics.

- All aspects of the beers being used to create the blend are taken into consideration.

- A blender undertaking this process typically selects one or two primary flavor attributes to focus on when choosing the beers to use. After making these decisions, additional beers can be added to the blend to enhance secondary characteristics and provide a fuller, more complex flavor profile. However, at this point, the blender should exercise caution not to try to take the beer into too many directions. Doing so can muddle, or dilute, the overall effect that the blender is attempting to capture.

- When dialing-in a cuvée blend, sometimes barrels or portions of barrels will be used to make adjustments to the blend. These adjustment portions can be added after putting together a test blend using the primary beers. Adjustment beers should be incorporated in the way seasonings are added to a dish while cooking, use them sparingly, adding just enough to dial-in the characteristics you are adjusting.

- Don’t concern yourself too much with final volume, choose to add beers that will enhance your blend and stop when the beers you have left bring nothing additional to the table.

As an example of cuvée blending: Imagine that you have just finished tasting samples of your 100-barrel golden sour program. During this time, you marked 10 barrels that were of particular interest due to their especially intense fermentation characteristics. After blending and packaging your golden sour, you go back to revisit those 10 barrels with a group of tasting friends. You find that 4 of those barrels have intense pineapple and guava tropical fruit notes, one barrel tastes like key lime pie, two barrels smell like you’ve been baking cinnamon sugar cookies in a musty old basement, two barrels smell exactly like cherry pie, and one barrel has an intense vanilla aroma and flavor. There are literally dozens of ways that you could combine these options to produce interesting and delicious specialty blends. If I were given these beers to play with, I might to the following:

- Pull the key lime barrel and make any adjustments that it needs to give it a moderate acidity with some residual malt sweetness. Serve as a single barrel release.

- Combine the 4 tropical fruit barrels (primary attribute) with one of the musty basement barrels (secondary attributes) to create a blend that balances fruity esters against mild funk and baking spices. Consider splitting this blend and dry hopping half of it with fruit-forward American or Australian hops.

- Combine the two cherry pie barrels with the vanilla barrel and remaining musty basement barrel. To this blend, add 2 lbs per gallon of whole tart cherries and age for an additional 1 to 2 months to create a lambic kriek inspired cherry sour.

You’ll notice that none of the blending methods that I’ve discussed involve much “mixing and tasting”. That’s not to say that when blending you won’t need to mix samples together to check your results, it’s just that these techniques come after a plan forms in your mind, not before. Every blender will develop their own style, but, for the most part, experienced sour blenders learn how to build a beer in their mind using the components they taste in their barrels. Only after forming a picture of the intended beer, will these blenders go back to verify their work by combining sample portions together. When creating this final test blend, I find it very helpful to cool and carbonate the blended beer. Evaluating the blend at serving temperature with carbonation will give you the most accurate picture of how your blend will taste after packaging.

Blending Day Tips

How to Collect Samples:

- If your beer is aging in barrels you have two main options for taking samples, through the bung or through a small secondary hole drilled into the head of a barrel. Alternatively, some sour brewers may install swivel valves into their barrels. While these are very handy, this practice is not common due to the added expense per barrel.

- If sampling beer through the bung using a wine/beer thief, I would recommend flushing the headspace in the barrel (or carboy) with CO2 after sampling. Blowing out the headspace with pure CO2 will help to remove excess oxygen that may have diffused into the barrel while sampling.

Many brewers prefer using the “Vinnie Nail” method, created by Vinnie Cilurzo of Russian River Brewing Company. To do this, simply drill a 7/64 ” hole into the barrel head. Then plug the hole using a McMaster Carr Stainless Steel Nail Size 4D (Catalog #97990A102). This method allows small samples to be collected from an aging barrel without introducing oxygen into the headspace or breaking the Brettanomyces pellicle.

Many brewers prefer using the “Vinnie Nail” method, created by Vinnie Cilurzo of Russian River Brewing Company. To do this, simply drill a 7/64 ” hole into the barrel head. Then plug the hole using a McMaster Carr Stainless Steel Nail Size 4D (Catalog #97990A102). This method allows small samples to be collected from an aging barrel without introducing oxygen into the headspace or breaking the Brettanomyces pellicle.

How to Transfer Beer From Barrel to Blending Tank:

- One of the cheapest ways to empty beer from an aging barrel is to drill and bung a hole in the head of the barrel which is designed for this purpose. On blending day you would pull this bung and quickly insert a vinyl tube to allow the beer to drain via gravity. This method can be messy due to spillage between pulling the bung and inserting the drainage tube. Additionally, this method requires your barrels to be elevated above your collecting tank.

- For a relatively low cost, self priming diaphragm pumps can be used to transfer beer directly through the bung using any food grade tubing. An example of such a pump can be found here.

- For larger barrel programs, it may be worth investing in a product called a “Bulldog Pup” pressure racking wand. Designed originally for the wine industry, this device uses CO2 pressure to transfer beer into the blending tank. This method both benefits the beer by reducing oxygen exposure and reduces dreg pickup through its design.

An alternative to the “Bulldog Pup” is a product called the “Rack it Teer”. This product also uses CO2 to transfer beer but additionally adds some safety features like a pressure release valve.

An alternative to the “Bulldog Pup” is a product called the “Rack it Teer”. This product also uses CO2 to transfer beer but additionally adds some safety features like a pressure release valve.

Additional Handling Considerations:

- Keep in mind that oxygen is the biggest enemy of aged sour beer. Brettanomyces and other microbes surviving within these beers become “starved” for nutrients, and can quickly consume excess oxygen to produce acetic acid.

- Pre-fill blending tanks with CO2, then allow beer to displace this gas when collecting for a blend.

- To maintain consistency, ensure that your entire blend can be homogenized within a single bright tank before carbonation or packaging.

Considerations After Blending & Packaging:

- It’s important to keep in mind that after blending, microorganisms from one batch of beer will suddenly be introduced into what is essentially a new environment. This can provide these microbes with nutrients and chemical precursors which they did not have access to previously. Therefore, a blended beer is likely to undergo certain changes shortly after blending.

- Diacetyl, Tetrahydropyridine, or Indole levels may spike for up to several months after blending. These tend to be transient issues that will resolve as long as the beer is given time to condition.

- Likewise, a blend can potentially become viscous with exopolysaccharides due to changes in Pediococcus metabolism. This so called “sickness” will also resolve with time.

- If bottle conditioning, allow several months to quality check a blend before its release. While carbonation generally only takes a few weeks to develop, the off-flavors noted previously can take several months to appear and then fade.

- One method used to “lock-in” a blend is flash pasteurization. This process has the benefit of preventing microbe based flavor changes. On the downside, pasteurized beers will not develop any further microbial complexity with age, nor will they be as resistant to oxidation.

- Filtration is another method used to both clarify a blend as well as reduce (but typically not eliminate) its microorganism cell counts. This process may help to reduce the risk off major off-flavor development after blending but still grants some ability for the beer to mature with age and resist oxidation.

Blending Tips for Common Sour Styles

Now that we have discussed blending from a mindset, planning, and process standpoint, I would like to share some of my thoughts and helpful tips on blending specific styles of sour beer.

Golden or Gueuze Inspired Sours

I like to think of golden sours as the IPAs of the sour beer world. When designing a great IPA, most brewers choose malts that will get out of the way and really let the hops shine. Furthermore, hops essentially define the flavor and aroma profile of any given IPA . In a similar fashion, golden sours live and die by their unique blend of fermentation characteristics. For the most part, golden sours are built on malt backbones which include some mix of pale malt, pilsner malt, wheat, oats, or some low SRM specialty malts. These malt bills provide a clean slate for fermentation characteristics to steal the show. When blending golden sours, you can target an acidity level that ranges anywhere from very light to strongly puckering. The predominant acid should be lactic acid, although some supporting acetic acid will add complexity. Avoid using beers that contain too much acetic acid. Without the complex malt backbone found in sour reds or sour browns, the acetic acid can easily come across as harsh. Tannins can also vary from completely absent to moderately astringent. Oak barrel character can range from absent to strongly present as well. The actual mix of fermentation characteristics that could be incorporated into a golden sour blend is nearly limitless. Common examples include beers that are fruity, floral, grassy, hay-like, barnyard, sweaty, musty, leathery, cheesy, spicy, mousy, metallic, doughy, toasty, yogurt-like, cola or sassafras-like, woody, or candy-like.

I like to think of golden sours as the IPAs of the sour beer world. When designing a great IPA, most brewers choose malts that will get out of the way and really let the hops shine. Furthermore, hops essentially define the flavor and aroma profile of any given IPA . In a similar fashion, golden sours live and die by their unique blend of fermentation characteristics. For the most part, golden sours are built on malt backbones which include some mix of pale malt, pilsner malt, wheat, oats, or some low SRM specialty malts. These malt bills provide a clean slate for fermentation characteristics to steal the show. When blending golden sours, you can target an acidity level that ranges anywhere from very light to strongly puckering. The predominant acid should be lactic acid, although some supporting acetic acid will add complexity. Avoid using beers that contain too much acetic acid. Without the complex malt backbone found in sour reds or sour browns, the acetic acid can easily come across as harsh. Tannins can also vary from completely absent to moderately astringent. Oak barrel character can range from absent to strongly present as well. The actual mix of fermentation characteristics that could be incorporated into a golden sour blend is nearly limitless. Common examples include beers that are fruity, floral, grassy, hay-like, barnyard, sweaty, musty, leathery, cheesy, spicy, mousy, metallic, doughy, toasty, yogurt-like, cola or sassafras-like, woody, or candy-like.

Sour Reds and Sour Browns

Sour red and brown ales offer a very wide range of blending possibilities. Flanders Reds and their American counterparts tend to have flavor profiles which are defined by a four-way interplay between specialty malt sweetness, lactic and acetic sourness, oak character, and estery fermentation characteristics. Sour browns tend to have less caramel type malt sweetness and are typically drier than their red cousins. Additionally, sour browns can show off a bit more acetic acid (in my opinion) and their fermentation characteristics can also range from fruity and wine-like to spicy, musty, and phenolic. Both styles make excellent potential candidates for specialty ingredients like fruits, vegetables, or spices. When blending sour reds, pay special attention to the malt sweetness and overall attenuation of the blender beers. Many classic examples of this style achieve a balance which is both sweet and sour by incorporating both young, full-bodied, beers as well as older, dryer, and more acidic, beers into the blend.

Sour red and brown ales offer a very wide range of blending possibilities. Flanders Reds and their American counterparts tend to have flavor profiles which are defined by a four-way interplay between specialty malt sweetness, lactic and acetic sourness, oak character, and estery fermentation characteristics. Sour browns tend to have less caramel type malt sweetness and are typically drier than their red cousins. Additionally, sour browns can show off a bit more acetic acid (in my opinion) and their fermentation characteristics can also range from fruity and wine-like to spicy, musty, and phenolic. Both styles make excellent potential candidates for specialty ingredients like fruits, vegetables, or spices. When blending sour reds, pay special attention to the malt sweetness and overall attenuation of the blender beers. Many classic examples of this style achieve a balance which is both sweet and sour by incorporating both young, full-bodied, beers as well as older, dryer, and more acidic, beers into the blend.

Fruited Sours

Probably the most diverse class of sour beers, your options for blending fruit sours are essentially limitless. Traditional lambic inspired examples will be based on blender beers with low-SRM malt backbones. Fruit lambic inspired sours should be blended with fermentation characteristics in mind, much the way gueuze-like golden sours are assembled. Remember that average rates of 2 to 3 lbs. of fruit per gallon will be added to these blends so if you would like to prevent the final beer from having a thin mouthfeel, the blend should target a moderate to full mouthfeel before the addition of fruit.

Probably the most diverse class of sour beers, your options for blending fruit sours are essentially limitless. Traditional lambic inspired examples will be based on blender beers with low-SRM malt backbones. Fruit lambic inspired sours should be blended with fermentation characteristics in mind, much the way gueuze-like golden sours are assembled. Remember that average rates of 2 to 3 lbs. of fruit per gallon will be added to these blends so if you would like to prevent the final beer from having a thin mouthfeel, the blend should target a moderate to full mouthfeel before the addition of fruit.

When branching out from lambic-style fruit sours, practically anything goes. Malt choices can range from low-SRM to highly kilned varieties, acidity can range from low to very high, and fermentation characteristics can target any mix that avoids off-flavors. There are a few guidelines that I would recommend for blending fruit sours, but keep in mind that these are not “rules”:

- When using dark or intensely flavored malts, more intense fruits tend to work better such as raspberries, grapes, or cherries.

- Blends with a light sulfur component can compliment stone-fruits such as apricots, peaches, nectarines, and plums.

- Fruits will taste the brightest and most natural when the acidity of the base beer approximately matches that of the fresh whole fruit.

- For most fruits, a usage rate of 0.5 to 1 lb. per gallon will give either a background fruit character or one that is in balance with the malt contribution. Rates of 2 lbs. per gallon will bring the fruit flavors to the forefront and mirror rates used in most fruit lambics. Rates of 3 lbs. or more per gallon will create a beer that shares many characteristics with a fruit wine.

Sours that Portray Strong Specialty Barrel Characteristics

When specialty barrels such as those used to age bourbon, tequila, gin, wine, maple syrup, vanilla, coffee, hot sauce, or mustard are introduced into a sour program, the first or second beers to come out of them will often pick up unique characteristics that may be worth showcasing in a blend. The trick here is that while most of these flavors may seem strong in the individual blender beers, they do dilute quickly when combined with beers that do not share these barrel qualities. If you want to showcase these flavors, you will most likely want to pick out the few barrels that contain them for use in a cuvée blend. From that point, small quantities of additional beers can be added to adjust secondary characteristics in the blend. If this is not your goal, these specialty barrel beers can be included in larger blends to add a background note which increases their overall complexity.

Dry-Hopped Sours

While most dry-hopped sours being produced today are based on golden sour blends, a wide variety of base beer styles could be used with success. When I am creating a blend to dry-hop, I like to incorporate fermentation characteristics that will meld into the flavor profile created by the hop varieties I intend to use, or vice versa. My goal is to create a beer in which the drinker cannot tell where the hops end and the fermentation begins. Some examples of this include:

While most dry-hopped sours being produced today are based on golden sour blends, a wide variety of base beer styles could be used with success. When I am creating a blend to dry-hop, I like to incorporate fermentation characteristics that will meld into the flavor profile created by the hop varieties I intend to use, or vice versa. My goal is to create a beer in which the drinker cannot tell where the hops end and the fermentation begins. Some examples of this include:

- Pairing tropical fruit fermentations that contain aromas and flavors reminiscent of mango, guava, pineapple, etc. with hops such as Australian Galaxy, Mosaic, Citra, Amarillo, or Nelson Sauvin.

- Pairing funkier Brettanomyces fermentations that showcase musty, earthy, doughy, or farmyard flavors with hops such as Hallertauer, Kent Goldings, Australian Topaz, or Northern Brewer.

- Pairing more phenolic fermentations that showcase flavors of black pepper, baking spices, tobacco, or wood with hops such as Saaz, Pacific Jade, Nugget, or Colombus.

Real World Blending Example

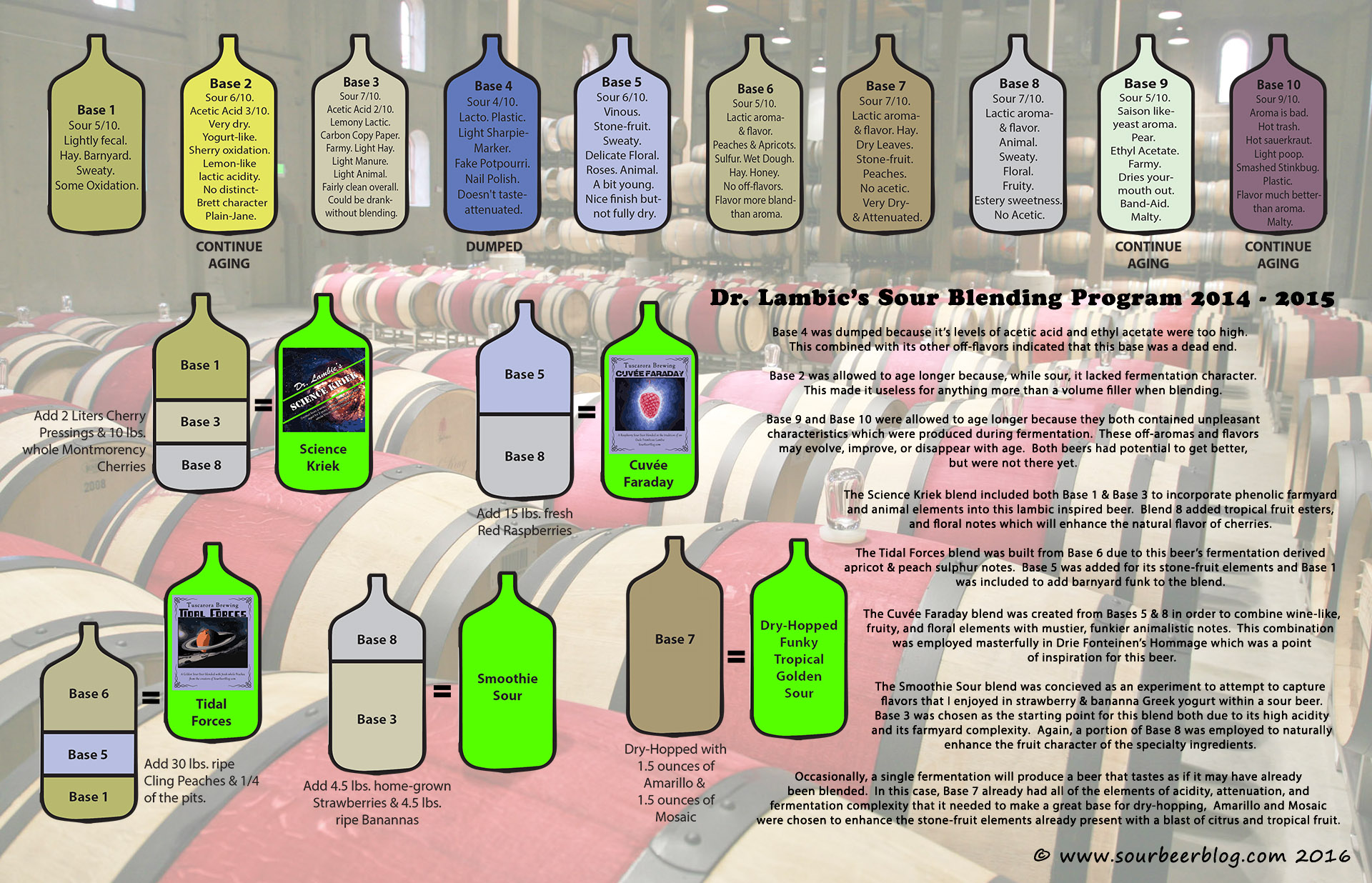

To wrap up this article, I would like to share a real world example of blending from my own sour beer program. The following 10 beers were brewed from July 2014 through January 2015. In July of 2015, Cale Baker and I sampled these beers and took the following tasting notes exactly as I have represented them here. From this point, we used portions of some of these beers to create four fruited sours and one dry-hopped sour. With the exception of Bases 9 & 10, all of the beers were brewed with a similar malt bill comprised of 60% Pale Ale Malt and 40% Wheat Malt. No hops were used in any of the recipes. Base 9 was designed after a Belgian Pale Ale and Base 10 was designed after an English Brown. Each beer was fermented with a different combination of Lactobacillus, Saccharomyces, and Brettanomyces strains. You will notice that of ten beers aged, only six were used in blending and one was dumped entirely.

Conclusion

If any particular practice can truly portray the art of sour beer creation, it must surely be blending. Through blending, a brewer can craft beers that no single process nor fermentation would be capable of producing. Furthermore, blending is a very human art. When we taste the world’s greatest sour beers, we are not tasting happy accidents or the fortuitous gifts of nature, but rather the passion and skill of a blender or group of blenders. We taste and enjoy these sour beers as their blenders intended them to be enjoyed.

My goal in writing this article has been to provide both craft and home brewers with educational and practical concepts related to sour beer blending. Yet furthermore, I hope that I will inspire those of you who have been uncertain about starting your own sour blending programs to do so. With a bit of planning, a bit of training, a lot of patience, and a steadfast commitment to quality, anyone can blend complex and delicious sour beers in your home or at your brewery. I personally love both beer and brewing, but there is nothing quite like the enjoyment I find in a blending day. I hope that you will give yourself the opportunity to experience it as well!

Cheers!

Matt “Dr. Lambic” Miller

Further Reading:

For those interested in blending Lambic style Gueuze, check out our reviews of the Armand 4 Seasons series by Drie Fonteinen. Each of these unique gueuzes was blended to capture the essence of a season in Belgium. I have never learned so much about the flavors possible within gueuze as I have from these four beers.

Also check out our article on Brewing and Blending a Lambic Style Kriek as well as our article on Brewing and Blending Flanders Red Ales.

Additional Sour Beer Blog Articles:

References:

Angotti, Fausto. “Top 20 Beer Tasting Tips.” Top 20 Beer Tasting Tips. The Brühaus, n.d. Web. 03 Feb. 2016.

Bickham, Scott. “Sources and Impact of Sulfur Compounds in Beer.” Sources and Impact of Sulfur Compounds in Beer. More Beer, 24 Oct. 2013. Web. 15 Jan. 2016.

“Blending.” Milk The Funk Wiki. N.p., 10 Oct. 2015. Web. 15 Jan. 2016.

Broas, Billy. “7 Ways to Improve Your Beer Tasting Palate.” The Homebrew Academy. Homebrew Academy, 11 Feb. 2010. Web. 03 Feb. 2016.

Guinard, Jean-Xavier. Lambic. Boulder, CO, USA: Brewers Publications, 1990. Print.

“Interview with Jean Van Roy of Cantillon.” Interview. Audio blog post. The Brewing Network. The Brewing Network, 8 May 2011. Web.

Shelton, Brothers. “Interview with Armand De Belder.” Interview. Audio blog post. The High and Mighty Beer Show. The Shelton Bros, 9 Mar. 2013. Web.

Smith, Brad. “Dimethyl Sulfides (DMS) in Home Brewed Beer.” BeerSmith Home Brewing Blog. BeerSmith, 10 Apr. 2012. Web. 10 Jan. 2016.

“Tetrahydropyridine.” Milk The Funk Wiki. N.p., 6 Dec. 2015. Web. 15 Jan. 2016.

Tonsmeire, Michael. American Sour Beers: Innovative Techniques for Mixed Fermentations. Boulder, CO: Brewers Publications, 2014. Print.