Hello Sour Beer Brewers!

Two weeks ago my friends and I had the opportunity to attend the American Homebrewers Association National Conference and Competition (NHC) in Grand Rapids, Michigan. We arrived a day early to check out the town and the local beer scene (which was awesome), and ended our first night there with a round of delicious Drie Fonteinen Oude Krieks bottled in 2009. As your personal ambassadors to the world of sour beers and brewing we viewed the rest of the conference as an opportunity to check out what the trends were in sour brewing among the homebrewers who showcased their beers both at club night and at the expo each day.

As a connoisseur of sour beers and a homebrewer myself, I think there are a lot of fears, myths, and misunderstandings floating around in the homebrewing community as a whole when it comes to these beers. Some of my goals for this site are to help brewers develop their palates for sour beer flavors, provide education, and to point them towards the resources they need to make excellent sour beers both at home and commercially.

This year at NHC there were two styles of sour beer that outweighed all others in popularity. These two styles were Berliner Weisse, a spritzy and refreshing sour wheat beer, and Flanders Red, a more complex oak aged sour red ale. There were a handful of really nice, well made, examples of these beers and unfortunately quite a large number of examples that fell short of my expectations.

The Berliner Weisses that were well made were free of off flavors like DMS (cooked corn) or highly enteric (manure) odors. They were light, had the tartness of fresh squeezed lemonade, and were either with or without Brettanomyces characteristics. While Brettanomyces is not typically used in this style’s fermentation or aging, it can add a nice twist to the style. Berliner Weisse can also be used as a nice starting point for a more complex sour beer that incorporates Brettanomyces or other ingredients such as fruit. I tasted a very nicely made and creative Red Beet Berliner Weisse brewed by Michael Crane of the Kansas City Bier Meisters. Check out this article about Michael’s use of red beets recently published by the famous beer writer Stan Hieronymus.

During club night I also drank a very tasty Papaya & Passionfruit Berliner Weisse fermented with Brettanomyces. After the conference, the brewer, Chris Kimber of the Kuhnhenn Guild of Brewers (Warren, MI), shared the story of how this beer came to be. I would like to thank Chris for allowing me to share his recipe and process for this beer and I would like to encourage our readers to check it out below because Chris’ story is a great example of how a brewer can steer a beer towards a goal through both measurement and correction as well as tasting and blending along the way. These processes are important for any beer but especially critical for sour beers. While many new brewers can follow a recipe and a set of processes, they often don’t adjust their process along the way and rather just wait to see how their beer tastes when it’s totally finished. An experienced brewer drives the beer towards his or her goal, making tiny adjustments along the way based on measurements they make or flavors they taste. Blending of batches is a powerful tool for any beer style but can be critical for lambics and other sour beers that not only age for years but also develop unpredictable characteristics based on a whole community of microbes living within them. Stay tuned in the future for more articles from us regarding both brewing processes and blending of sour beers. For more information on avoiding off flavors in Berliner Weisses check out our Ask Dr Lambic article on the style.

Even though Berliner Weisses were popular this year, they were far outweighed by examples of Flanders Red Ale. Unfortunately this is a style that is largely misunderstood by both the homebrewing and craft brewing community at large. Throughout the conference I drank one very well made example of the style named 8 Ball Sour, made by the club Muskegon Ottawa Brewers (MOB). This example showcased all of the positive qualities of a well made Flanders Red Ale. The beer was well attenuated without any residual sugars while still containing complex sweetness provided by caramel malts. The sour profile was nicely tart from lactic acid with only the lightest background note of acetic acid (vinegar) to add complexity. The beer had a pleasant oak flavor that was not out of balance with the malt flavors. Finally, the beer’s fermentation tasted clean and healthy without any other notable off flavors such as green apple, solvent or fusel alcohols, or yeast autolysis.

In opposition, I had a large number of examples of this style that were poorly made. These beers included examples that were either too strongly oak flavored (tasting like bourbon), were under-attenuated (tasting very sweet or syrupy), or tasted like they contained traces of nail polish remover (acetone: which comes from fermenting a sour beer too hot). However, outweighing these examples two to one were beers that tasted like vinegar bombs. I will go on record here as emphatically stating that a Flanders Red Ale should never taste like malt vinegar. This is a widespread point of confusion for this style because there are several well known commercial examples of Flanders Red Ales, made in Belgium, that have strong vinegar flavors. While these beers may be widely available in the US craft beer market they are sadly poor examples of the style.

When making a Flanders Red Ale, brewers should use Lactobacillus with or without Brettanomyces to produce a pleasant level of lactic acidity in the beer. This souring level should be in balance with the malt and oak character to produce a complex and delicious flavor profile while maintaining an overall easy drinkability to the beer. While aging a Flanders Red (or any sour beer for that matter), extreme care needs to be taken to reduce oxygen exposure to the aging beer because overexposure to oxygen will lead to high levels of vinegar in the final product. A good Flanders Red will be a three way balance between complex malt flavors including caramel, soft lactic acidity, and a pleasant oak presence which helps dry out the finish. If a commercial or home brewed Flanders Red is sharp or overpowering in any of its flavor components or contains an unpleasant level of vinegar then it is not a well made version of the style.

Luckily, not all of the sour beers at this year’s NHC tasted like they belonged on boardwalk french fries! I had several other very nice sours at club night including an aged lambic called Poltergueuze made by Adam Juncosa of ANNiHiLATED and a Brettanomyces IPA at the St. Louis Brews club night booth.

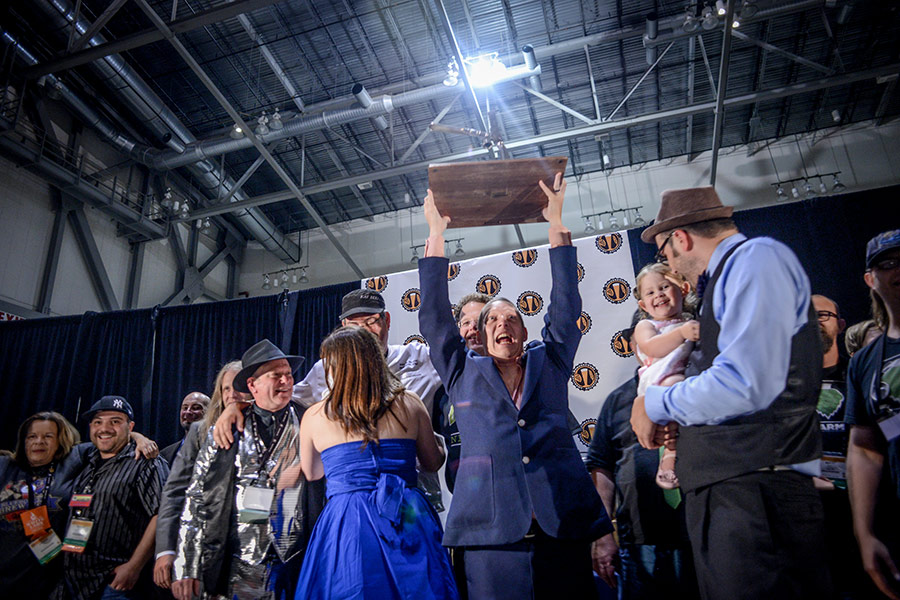

I want to take the opportunity here to congratulate all of the homebrewers who helped The Brewing Network Club (my club!) win Club of The Year. I can honestly say that I have learned more about brewing and beer from listening to shows on The Brewing Network than from any other single reference or educational source. If fact, I would highly encourage anyone interested in learning more about brewing the Berliner Weisse or Flanders Red styles to check out the shows that have been recorded by Jamil Zainasheff on those styles for The Jamil Show and Brewing With Style on the BN. #BNARMY4LIFE

Lastly, I want to mention that I certainly did not get a chance to try every single sour beer being served at the conference and that surely there were other great sour beers that I may have missed. My intention in critiquing off flavors and other brewing flaws found in certain sour beers is not to offend or diminish the hard work of home or craft brewers, but simply to educate and help raise the bar for sour beers within our community as a whole. I look forward to trying everyone’s sour beers next year! See you all in San Diego in 2015!

Cheers!

Matt

Chris Kimber’s Passionfruit/Papaya Brett Berliner Weisse

One of the best things in brewing are the happy accidents that happen from time to time. You can create a recipe, but what unfolds once you start to brew it can sometimes mutate into something much bigger than you had originally planned.

After reading a number of articles about the Berliner Weisse style, I decided I finally wanted to try and make one myself. The summer was coming and I wanted a super-sessionable summer drinker on hand, as my wife prefers sour/tart beer. I’m kind of a glutton for punishment and also decided it would be my first foray into decoction.

The original plan was to do 10 gallons of a single decoction, no-boil 60/40 pils/wheat wort, that was no more than 1.036 OG. The decoction process went well, but of course, I wound up getting 100% mash efficiency and ended up with 1.041 pre-boil! Worried that this would be too boozy for the BJCP style, I wound up diluting it back down to 1.036 with distilled water, which brought my yield to just about 15 gallons total. I brought the wort right up to 210 degrees and cut the flame.

I had chosen to use East Cost Yeast’s Berliner Blend for this beer, as I had great success with their BugFarm, BugCounty, and various Brettanomyces strains previously. I made a starter, and it definitely smelled sour before pitching it in the beer. Fast forward 3 days later, no visible signs of fermentation, shit. “Let’s just give it another day or two and see if the kolsch yeast takes hold.” On day 5 I pulled a sample from the fermenter, the beer had only dropped 2 points and had already taken on a pretty acidic flavor.

The kolsch yeast apparently didn’t survive the trip to my door, but the 2 strains of Lactobacillus had.

It was Friday night, having it sit another 12-24 hours before I could make it to the local homebrew supply shop was out of the question, it was a no-boil, and I was hitting a very critical point with the beer. I had a second generation strain of Brettanomyces custersianus sitting in my fridge waiting to go into a saison the following week, “Would this beer still be good?” I thought?

My experiments with B. custersianus had been positive overall, one selling point was the fruity/candy aroma and flavors I got, but also the minimal funk. So the deed was done, I pitched the B. custersianus in the fermenter and the beer took off within a couple hours. I was relieved.

Fast forward a couple weeks: I knew that eventually I would split this beer into three carboys and put two of them on fruit, I just wasn’t sure which fruits. I knew I wanted fruits that aren’t typically seen in classic versions of this beer: tropical, exotic, and tart. Since it was mid-March in Michigan, I didn’t have a lot of options. I cleared the supermarket out of all their passion fruit and picked up the bigger papaya I could find. I enjoyed both of these fruits fresh, but had never used them in a brew before.

Once the secondary fermentation had completed with both fruit versions, I kegged them and let them condition for a week or so before trying them. The acidity of both versions was very, very intense, however the passion fruit version was definitely a bit too tart. I experimented with blends of both version until finding one that my wife and I both really liked, and blended them into a new keg for more conditioning.

Voila, Passionfruit/Papaya Brett Berliner Weisse!

I’m really happy how the beer turned out overall, it was a huge success at NHC and I wound up getting lots of great compliments.

If someone wanted to reproduce this beer here are the details:

Est OG: 1.036 Est Efficiency: 75%

Grist: 60% German Pils 40% German Wheat

Hops: 1.5 IBUs of Fuggles (added during decoction)

Yeast: Lactobacillus brevis Lactobacillus delbrueckii Brettanomyces custersianus

Starter: • Make a starter w/ apple juice and the two strains of Lactobacillus 3 days before brewing • Make a starter for the B. custersianus the same day that you brew

Mash: • Mash in around 125-130 degrees, rest 30 mins. • Pull decoction of about 1/3 of the mash and bring up to 155 for a 10 minute protein rest. • After rest, add hops and boil decoction for 10 mins. • Add decoction back into mash hoping to hit mid-140s (if possible, bring mash temp up to 146) and do a 30 minute saccharification rest. • Mash out at 168 degrees, add rice hulls • Sparge with 168 degree treated water, sparge only how much wort you want in your fermenter!

Boil: • Collect wort and bring temperature up to 210 degrees then cut the flame.

Primary: • Oxygenate your wort • Pitch the Lacto starter • Let sit for 5 days @ mid to high 60s • After 5 days pitch the B. custersianus • Wait 7-10 days

Fruit prep: • 1 large papaya, peel, scoop the seeds and cut into chunks that will be able to fit easily into the neck of the carboy. Freeze. • 7-10 passionfruit. Slice in half, scoop the seeds and fruit goop into a bag. Freeze.

Secondary: • Thaw fruit before racking. Once thawed put in the carboys separately. • Rack ~5 gallons onto each fruit. • Wait at least 4 weeks at mid to high 60s.

Bottle or keg, and let it condition for 2-3 weeks before serving.

Chris Kimber / Kuhnhenn Guild of Brewers (Warren, MI)