Hello Sour Beer Friends!

Drinkers of wine and tea will likely be familiar with a broad class of organic biomolecules known as tannins. Nearly ubiquitous amongst plant species, tannins are large molecules which are stored inside special organelles within a variety of plant cells. These chemicals play what is believed to be a minor role in plant growth and development and a major role in protection against consumption by herbivores. Tannins are only released from their storage units upon damage to plant tissues. Once released, these chemicals dissuade would-be foragers by producing an astringent, bitter sensation on the palate.

Functionally, tannins bind to a wide variety of proteins, forming large complexes. They produce their palate drying astringency by stripping salivary proteins from the surface of the tongue. In traditional brewing practices, tannins are typically thought of as something to be avoided. Tannins extracted from grain during mashing or from hops during excessively long boils can add a harsh astringent sharpness to classic ale and lager styles. Additionally, the complexes that tannins form when binding to malt proteins can produce “chill haze”, a cloudiness which tends to only form when a beer is cold.

Functionally, tannins bind to a wide variety of proteins, forming large complexes. They produce their palate drying astringency by stripping salivary proteins from the surface of the tongue. In traditional brewing practices, tannins are typically thought of as something to be avoided. Tannins extracted from grain during mashing or from hops during excessively long boils can add a harsh astringent sharpness to classic ale and lager styles. Additionally, the complexes that tannins form when binding to malt proteins can produce “chill haze”, a cloudiness which tends to only form when a beer is cold.

While there are a number of brewing situations where tannins should be minimized, they actually make up an important, and often overlooked, component of the flavor profile of many sour beers. Although I’ve understood this conceptually for some time, I’ve recently gotten to experience it first hand in my own sour blending program. About one year ago, site author Cale Baker and I began a series of experimental brews with the goal of producing sour beers which could be blended to recreate the flavor profile of a classic Belgian gueuze. While I will be writing an upcoming article which fully details this blending program, I felt that one of its shortcomings would make a valuable educational contribution to this topic. This is because the only group of flavors found in classic gueuzes that our program has thus far failed to recreate are those produced by tannins.

For those who would like a refresher course on the traditional mashing and brewing methods used to produce lambic, check out my coverage of that topic both in this article on brewing and blending krieks and in this article about Cantillon Kriek. When designing our brewing process, we chose not to include aged hops in the boil or utilize a traditional turbid mash because we did not want to restrain the activity of Lactobacillus or create a highly dextrinous wort which would take a long time to attenuate. To this end our program has been highly successful. The beers it has produced thus far have all developed proper levels of acidity, attenuation, and a myriad of complex Brettanomyces and mixed fermentation characteristics appropriate for use in gueuze blending. What the beers are lacking, however, is a classic astringency and tannic bite present in many gueuzes such as those produced by Drie Fonteinen, Cantillon, Oude Beersel, and Lindemans.

To those who are unfamiliar with the gueuze style, it may seem odd that someone would want to introduce astringent compounds into a beer. But in the case of a highly attenuated sour beer like gueuze, these tannins add structure and fullness to the body and mouthfeel, as well as a dryness in the finish which are all characteristic to the style. Wine drinkers will recognize these same traits in dry red wines, which without their tannins would be thin and lackluster. Overall, both the right variety and level of tannins can add complexity to the drinking experience of many sour beers. I say drinking experience because in the truest sense, astringency isn’t a flavor, but rather a tactile sensation on the palate.

As I just hinted, gueuzes are not the only sour beers to prominently feature tannins as a part of their flavor profile. Both Flanders Reds and a wide range of fruit sours also have moderate to high tannin content. In the case of Flanders Reds, these tannins are extracted from wood during the beer’s long aging in oak or chestnut barrels. On the other hand, fruit sours, like wines, derive their tannins directly from the skins and seeds of the fruit being added. This is one of the main flavor differentiators between beers aged on whole fruit versus beers with fruit juice added.

Now that we have some background regarding the presence and potential importance of tannins in certain styles of sour beer, lets discuss the difference between good and bad tannin content as well as look at how to incorporate tannins into our own sour beers:

Tannin Varieties and their Effects

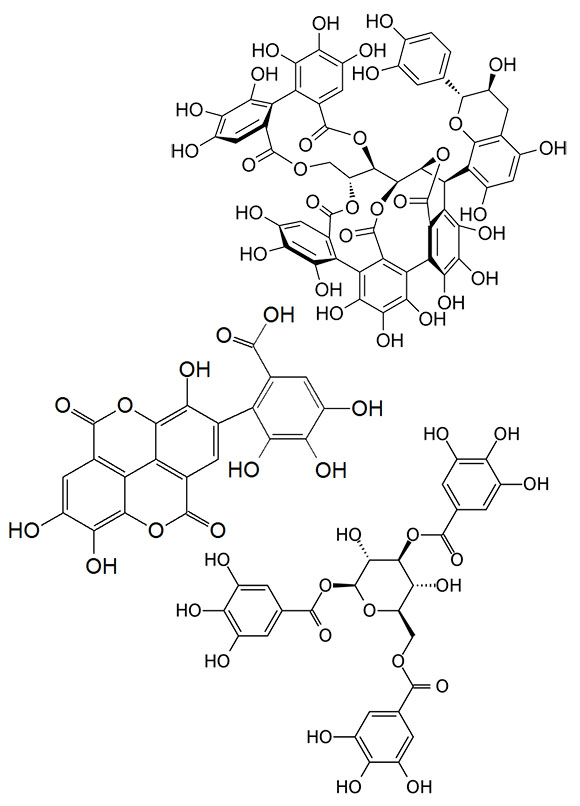

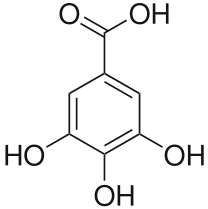

Broadly speaking, tannin is a catch-all term used to describe a very wide variety of polycyclic phenolic compounds. In general, the smaller a tannin molecule, the more likely it is to produce a sharp astringency coupled with a bitter flavor on the palate. Inversely, the larger a tannin molecule (or complex of tannin and protein molecules), the less bitter it will taste and the softer the astringent sensation it produces will be. The types of tannins which are relevant to brewing can be classified into one of three groups: Hydrolysable, Condensed, or Complex.

Hydrolysable tannins are fairly large molecules which can also come bound to sugar groups. These tannins produce a softer bitterness and astringency which is desirable in many sour beers. These tannins occur in moderate concentrations in the skins of a variety of fruits as well as in high concentration in oak and chestnut woods.

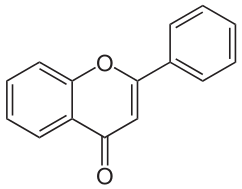

Condensed tannins are based on a functional unit called Flavone and may be referred to in some texts as catechins.

Condensed tannins are smaller compounds found in the bark and seeds of many fruit bearing plants. These are also the tannins present in both hops and barley malt husks. These tannins produce a sharper and generally unpleasant level of bitterness and astringency. As a result, we are looking to limit the extraction of these types of tannins into our sour beers. As I discussed earlier, lambic varieties may contain these tannins to beneficial effect. How they do so brings us to the third group…

Complex tannins are groups of molecules from either of the two previous classifications bound together. These complexes can also bind together with proteins and molecules called anthocyanins, which are usually responsible for the colors extracted from fruits into a sour beer. These large complexes have the lowest bitterness and softest astringency of any of the tannins discussed. The ability for tannins to link together like this explains several of the changes that occur to a sour beer as it ages. The first of these aging effects being a softening of a beer’s astringency over time. This is why a gueuze, which at the time of its brewing may be quite sharp and bitter with condensed tannins, will soften with age and have a pleasant tannic quality by the time it is released. The second effect is the inevitable lightening of a fruited sour beer’s color over time. As a beer ages, these tannin complexes can become large enough to actually settle out of a beer altogether, forming a fine sediment on the bottom of the bottle (regardless of whether a beer contains live microbes, which will form their own sediment as well). As anthocyanin molecules bind into these complexes and fall out of a beer, its fruit-derived color is reduced.

Brewing and Blending With Tannin Content in Mind

There are several ways to add or remove tannins from a sour beer. Before doing so however, keep in mind that not every beer may benefit from the addition of tannins, and those that do can be made harsh from too much tannin content. As with any brewing or blending technique, your palate must be your ultimate guide. There are no chemical tests or special calculators that can decide how much tannin is right. Moreover, the addition of tannins to a sour beer cannot be used to cover up flaws or fix off-flavors. Here are a few situations where tannins may improve your sour beer’s drinking profile:

- You’re trying to reproduce the full flavor profile of a lambic gueuze or fruit lambic.

- You’re producing a Flanders Red or Brown and aging the beer in glass, plastic, or stainless steel.

- You’re blending a sour beer with fruit juice and would like to enhance the beer’s complexity to be more like whole fruit.

- You have a fully attenuated sour beer which tastes thin and lackluster in the body or finish.

- You have any sour beer which you feel would benefit from a more wine-like complexity.

Adding Tannins to Sour Beer

Once you decide that you would like to incorporate tannins into your beer there are several ways to do so:

- During the Brewing Process

- This method involves the purposeful addition of tannins into a beer during the brewing process and is most applicable to sour beers which will enjoy a long aging time before being served.

- To increase the tannin extraction from grain. Consider sparging with slightly more alkaline water (pH 5.5 to 6.5), sparging hotter (175-190 F), or both.

- To increase your tannin extraction from bittering hops add these hops early into a long boil. Traditional lambic boils may last up to 4 hours and utilize about 1 oz. of aged hops per gallon of wort. These aged hops don’t add much alpha-acid bitterness but they do add a significant level of condensed tannin content to the wort.

- These methods produce a sharp and relatively harsh tannin content early on in a beer’s life which will require time to mellow and age out. Keep this in mind if designing a beer that will employ either of these practices.

Via Wood Aging

Via Wood Aging

- Oak, chestnut, and a variety of other woods can contribute tannic complexity to a sour beer.

- When choosing an oak toast level, low to medium toasts will contribute character found in many white or red wines while higher / heavier toasts will contribute flavors more closely associated with whiskey or oak aged spirits.

- Tannin extraction from any wood is related to both the surface area of the wood exposed to the aging beer and the length of exposure time. When aging in barrels you have only one variable to control: time. When using chips, cubes, or spirals, the amount to use and length of time to leave them in the beer can vary greatly. A good starting point would be to use 1 to 2 ounces of wood per 5 gallons of beer and taste the beer every 2 to 4 weeks to dial in the right tannin contribution.

- Keep in mind that wood aging is a more complex topic than simply tannin extraction. Wood sugars, vanillin, and micro-oxygenation will all alter a sour beer’s flavor profile independent of tannin extraction.

- More more detail on oak aging, check out our discussion on Brewing a Flander’s Red Ale.

-

Via Fruit Additions

- In my opinion, adding whole fruit to a well produced sour beer or blend of beers can create some of the most dynamic, complex, and delicious products on the market.

- When adding fruit to a sour beer, the form in which it is added will directly affect the speed at which tannins are extracted as well as the variety of tannins extracted. The more damaged the skin of the fruit, the faster tannins and anthocyanins (color molecules) will be extracted. Crushing or pre-freezing fruit before adding it to sour beer can help to speed the extraction process. This may be desirable because long aging times on whole fruit seeds can increase the proportion of sharper, more astringent condensed tannins.

- In general, any stems should be removed from the fruit before its addition to a beer. The stems and the seeds of many fruits contain harsher condensed tannins. In most cases, leaving the seeds in the fruit is fine, but avoid crushing or breaking the seeds open, as this will greatly enhance the levels of these undesired tannins in the beer.

- When adding fruit to a sour beer, a number of compounds including color, aroma, esters, and sugars will be extracted into the beer in a relatively short time frame spanning days to weeks. On the other hand, tannins can continue to be extracted for several months after the fruit’s addition. I would recommend tasting the beer shortly after the refermentation of fruit sugars has subsided to evaluate the fruit character in the beer and to determine if the beer would benefit from any further tannin extraction. If so, leave the fruit in the beer and continue to taste it periodically. If not, rack the beer off the remaining fruit flesh, skins, and seeds so that it can be served or continue to age without further tannin pickup.

- Via Dry-Hopping

- Dry-Hopping is a method which can increase the tannic complexity of a beer in a matter of days. In addition, dry-hopping provides a sour beer with a bouquet of complex hop aromas and flavors that can span from herbal, floral, or piney to citrus, berry, melon, and tropical fruit.

- This method can be used to fill out a sour beer which is otherwise good, but may have a few “holes” or bland spots in its flavor and aroma profile.

- When choosing a hop or combination of hops, I tend to use varieties which will augment already existing characteristics in the base beer created by Brettanomyces or fruit additions.

- An appropriate dry-hopping rate would be 1 to 3 ounces per 5 gallons of finished sour beer, with a contact time of 3 to 10 days on average. Using more hops and allowing them to remain in contact with the beer for longer periods of time tends not to provide any further hop character, but will continue to add tannins to the beer.

- The tannins provided by dry-hopping are typically a bit sharper but can taste very nice in the restrained amounts suggested here. Over dry-hopping or allowing the hops to remain in the beer for too long can easily push the flavor profile past complex and into abrasive.

- Check out our article on Dry-Hopped Sour Beers for more discussion on this topic.

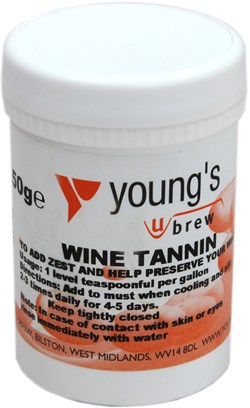

Through the Addition of Grape / Winemaker’s Tannin

Through the Addition of Grape / Winemaker’s Tannin

- There are concentrated grape-skin tannin products on the market available for winemaking. These products may be useful to adjust the tannin content of sour beers with or without fruit additions. Because tannins provide a tactile sensation rather than a true flavor, if these products are used in moderation, the results may be indistinguishable from tannins derived from other sources.

- These products are generally used at a rate of 1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon per gallon for dry red wines. When using to adjust a sour beer, I would recommend starting at 1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon per 5 gallons and increasing from there as needed.

- These products should be dissolved in boiling water and then cooled before adding to a beer. It can take up to 2 weeks to taste the full effect that these products will have on a sour beer, so allow this time to pass before tasting and deciding if more tannin is needed.

Removing Tannins from Sour Beer

There may be cases where a beer has developed too much tannic character. If a sour beer leaves your mouth feeling like it’s been dried out, or if a beer has an otherwise sharp and unpleasant astringency, too many tannins could be the culprit.

The best way to reduce tannins in a sour beer is to avoid introducing too many tannins in the first place. Especially in cases where fruit or hops have not been added to a beer, this comes back to brewing process. If you have produced a base beer that is too tannic, then on subsequent brews ensure that your mash and wort pH remain between 5.2 to 5.6 during the mash, sparge, and boil to avoid extracting excess tannins from the grain or hops. This may require an adjustment of both the mash and sparge water with either food-grade lactic or phosphoric acid. Additionally, keep the temperature of your sparge water between 168 and 170 F. One other potential source of unwanted tannins can be a malt crush that is too fine. Pulverizing the malt husks will make it easier for tannins to be extracted even when remaining within the proper pH and temperature ranges. The best crushes break the malt kernel into small pieces without shredding the malt husks.

As noted earlier, the concentration of tannins extracted from fruit, wood, or hop additions increases over time, so make sure to taste your beers on a regular schedule to ensure that they don’t become too tannic. However, mistakes are natural and if a beer becomes too tannic there are three potential ways to remedy the problem:

- Age

- Regardless of the source of tannins, as a beer ages, its tannins are likely to form large complexes and become softer, more pleasant, and less astringent. Eventually, these complexes will settle out or can be filtered out of the beer altogether.

- This process can take months or even years to occur.

- Blending

- I have stated before that blending is one of the most powerful tools in a sour brewer’s toolkit. This is especially true in regard to a component like tannins, which can be wonderful at one concentration and overbearing at another. A savvy brewer will always keep an option for blending available to himself or herself. If there is ever a situation in which you are worried that you might overdo an addition, hold some beer in reserve for blending back into the final product.

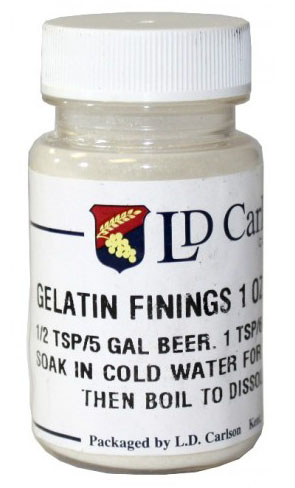

Finings

Finings

- Protein based finings will bind to and remove a wide variety of tannins based on the molecular weight of the tannins themselves.

- Gelatin based finings come in a variety of formulations which target different molecular weight tannins. Because smaller, lower molecular weight tannins tend to me more harsh and bitter, my recommendation would be to first attempt using a product which targets these.

- PVPP (polyvinylpolypyrrolidone) is an insoluble polymer that targets small tannins and precipitates them from solution. This product may be especially helpful if a fruit or hop addition has left a sour beer tasting too astringent.

- Always follow the manufacturer’s directions closely in regards to concentration, contact time, and working temperatures. It is easy to overuse these products and ruin a beer which may have become wonderful with age.

Hopefully this discussion has been both educational and instructive for those brewers beginning to fine tune their sour beer processes. Tannin adjustment is unlikely to be one of the most important decisions that a sour brewer will make. However, once you find that you are consistently producing beers that are free of off-flavors and achieving the levels of acidity and funk that you desire, then taking tannins into consideration will help you enhance complexity and achieve a balance found in a number of world-class sours. Good Luck and Happy Brewing!

Cheers!

Matt “Dr. Lambic” Miller

References:

Chung, King-Thom, Tit Yee Wong, Cheng-I Wei, Yao-Wen Huang, and Yuan Lin. “Tannins and Human Health: A Review.” Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 38.6 (1998): 421-64. Web.

Guinard, Jean-Xavier. Lambic. Boulder, CO, USA: Brewers Publications, 1990. Print.

Palmer, John J. How to Brew: Everything You Need to Know to Brew Beer Right the First Time. Boulder, CO: Brewers Publications, 2006. Print.

Pambianchi, Daniel. “Tannin Chemistry: Techniques – WineMaker Magazine.” Tannin Chemistry: Techniques. WineMaker Magazine, 01 Apr. 2011. Web. 01 Aug. 2015.

Petridis, Georgios K. Tannins: Types, Foods Containing, and Nutrition. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science, 2011. Print.

Puckette, Madeline. “What Are Tannins In Wine?” Wine Folly. Wine Folly, 05 Apr. 2013. Web. 01 Aug. 2015.