Understanding, Brewing, and Blending a Lambic Style Kriek

Hello Sour Beer Friends!

Of all the wonderful sour beer styles produced, the group I have always gravitated toward are the fruit lambics of Belgium, specifically Oude Kriek. One of my goals since becoming a home brewer has been to reproduce examples of this style that could stand in the same league as examples from my favorite Belgian master blenders. While this is no easy task, I have come to believe that it is not impossible. With the proper sour brewing and blending program, a thoroughly trained palate, and the desire to actually go for it, excellent lambic style krieks can be produced on both homebrew and commercial scales. To aid you in this process, I will discuss the style, excellent commercial examples, and strategies to use when trying to produce your own. Before we review kriek in detail though, I would like to take a step back and look at the origins of sour beer in general and how beer evolved from a form predating recorded history into its varied modern forms.

Sour Beer Origins

There are a number of theories detailing how beer may have been discovered or produced by humans in the earliest agrarian societies. These theories generally fall into one of two camps. The first camp postulates that the earliest beers were produced by accident. The idea here is that grain being stored in clay containers got wet accidentally but was then dried out, thus becoming malted. At some later point, this malted grain was flooded by rainwater and fermentation began spontaneously via the wild yeasts and bacteria present throughout nature. In this version of the theory, mankind discovers that their bubbling grain and water mixture both tastes good and, because it contains alcohol, also produces pleasant mental effects.

There are a number of theories detailing how beer may have been discovered or produced by humans in the earliest agrarian societies. These theories generally fall into one of two camps. The first camp postulates that the earliest beers were produced by accident. The idea here is that grain being stored in clay containers got wet accidentally but was then dried out, thus becoming malted. At some later point, this malted grain was flooded by rainwater and fermentation began spontaneously via the wild yeasts and bacteria present throughout nature. In this version of the theory, mankind discovers that their bubbling grain and water mixture both tastes good and, because it contains alcohol, also produces pleasant mental effects.

The second camp theorizes that early man understood from observation of nature that spontaneous fermentation existed and then purposefully attempted to recreate it using a variety of food-stuffs such as honey, fruits, and grains. A number of fallen fruits will spontaneously ferment and animals often preferentially seek out these alcoholic treats. It stands to reason that early man may have seen this occur, and successfully attempted to recreate the process on a larger scale.

Regardless of how the first beers arose, they most definitely made use of spontaneous fermentation by a mixed culture of wild microbes. Depending on the random mix of microbes involved, these beers (or mixed fermented beverages, as it seems many early cultures mixed their fermentables to produce what we would consider to be beer-wine-mead hybrids) would have either started off already partially sour or would become sour over time as they aged. Those who have ever experimented with their own spontaneous fermentations are well aware of how unpredictable, and often undrinkable, these beers can be. Additionally, any beer with a mixed culture of wild microbes has the potential to become more acidic over time. Spontaneous beers that taste delicious after the first year may be chokingly acidic after an additional year. Thus from the very earliest days, brewers have been searching for processes that would make beer more predictable, last longer in storage, and have the best possible flavors.

A number of processes are able to do this. Through experimentation and observation across many generations the practices involved in modern brewing were tested and refined. Boiling the wort and then back-slopping with the sediment from batches of beer that had already turned out well put selective pressure on wild yeasts eventually eliminating strains with undesirable traits. Over centuries, these practices domesticated wild yeasts into the multitude of modern brewer’s yeast strains that we have today. The process of back-slopping with already fermented beer eliminates much of the chance for undrinkable batches but does not prevent eventual souring with age as these “refined cultures” still contained a variety of microorganisms.

During the Middle Ages, the addition of hops into the brewing process provided beer with some additional resistance to souring due to the hop’s ability to restrain the growth of Lactobacillus. In many brewing cultures, beer was either drank fresh or blended with fresh beer to avoid sour flavors or reduce these flavors. Only with the invention of the microscope, the development of modern germ theory, and the subsequent isolation and creation of pure brewing yeast cultures did truly “clean” beers become possible.

During the Middle Ages, the addition of hops into the brewing process provided beer with some additional resistance to souring due to the hop’s ability to restrain the growth of Lactobacillus. In many brewing cultures, beer was either drank fresh or blended with fresh beer to avoid sour flavors or reduce these flavors. Only with the invention of the microscope, the development of modern germ theory, and the subsequent isolation and creation of pure brewing yeast cultures did truly “clean” beers become possible.

There is an alternative to all of this “cleaning up” of beer that occurred historically throughout much of Europe, and this is where our narrative returns to sour beer and the production of lambic. Another way to produce beer that is both delicious and able to be aged over time is to embrace sour flavors rather than try to eliminate them. This is exactly what happened historically within the Zenne (Senne) Valley and surrounding regions (modern day Brussels and the areas directly west of Brussels, Belgium). Referred to as Pajottenland (Payottenland), the brewers in this region learned centuries ago that spontaneously fermented beers could be aged and blended to produce products with refreshing acidity, crisp cracker-like malt flavors, and varying degrees of complexity with additional flavors ranging from those of tropical fruits to those of aged “stinky” cheeses and leather.

“Lambic”, an appellation protected by law in Belgium, much like “Champagne” in France, refers both to a style of brewing and to a specific product. Lambic brewers formulate their recipe using around two thirds malted barley to one third un-malted wheat. These are mashed using a process called turbid mashing which results in a wort that is full of long-chain sugars and some starches. This type of wort is only partially fermentable by Saccharomyces, and thus leaves a significant number of nutrients available for organisms such as Brettanomyces, Lactobacillus, and Pediococcus. After a hot sparge, which extracts these sugars, starches, and some tannins, the wort undergoes a long boil to which aged hops are added at a rate of around 2 lbs. per barrel. The use of aged hops inhibits Lactobacillus without adding significant bitterness to the beer. These hops do add character to lambic beers though including some cheesy and herbal aromas and flavors.

After boiling, the hot wort is pumped into a coolship, which is a wide and shallow metal tray typically located in the attic or upper floor of the brewery. The wort remains in this large pan as it slowly cools to room temperature. During this cooling, the wort is exposed to the air flowing through the coolship room and becomes inoculated with whatever mix of microorganisms happen to be floating in that air. After cooling, the wort is mixed and pumped into oak barrels to undergo spontaneous fermentation by both the organisms picked up while in the coolship as well as the resident organisms already living in the barrels. This beer, now simply called “lambic” or sometimes “unblended lambic” ages in these barrels for up to several years. The beer becomes dryer (more attenuated), more acidic, and funkier as it ages. Certain barrels of unblended lambic that develop unique, interesting, or just overall balanced character may be served still and straight. However, it is more common for barrels of differing ages and characteristics to be either blended together to produce gueuze or blended with fruits to produce fruit lambics such as kriek and framboise.

After boiling, the hot wort is pumped into a coolship, which is a wide and shallow metal tray typically located in the attic or upper floor of the brewery. The wort remains in this large pan as it slowly cools to room temperature. During this cooling, the wort is exposed to the air flowing through the coolship room and becomes inoculated with whatever mix of microorganisms happen to be floating in that air. After cooling, the wort is mixed and pumped into oak barrels to undergo spontaneous fermentation by both the organisms picked up while in the coolship as well as the resident organisms already living in the barrels. This beer, now simply called “lambic” or sometimes “unblended lambic” ages in these barrels for up to several years. The beer becomes dryer (more attenuated), more acidic, and funkier as it ages. Certain barrels of unblended lambic that develop unique, interesting, or just overall balanced character may be served still and straight. However, it is more common for barrels of differing ages and characteristics to be either blended together to produce gueuze or blended with fruits to produce fruit lambics such as kriek and framboise.

With an understanding of where unblended lambic comes from, we can now delve into kriek as a style. There are numerous American and Belgian beers with the name kriek, krieken, or kriekenbier. An enormous number of American beers with the kriek moniker have little to nothing in common with lambic style krieks. There are also Belgian examples of the style which have been sweetened or had their flavors significantly toned down to appeal to younger drinkers (whom they apparently believe are looking for something resembling cherry flavored soda). My goal for this article is to provide brewers with an understanding of what characteristics you will find, and which flavors you won’t find, in a world-class lambic oude kriek, provide recommendations for commercial examples for palate training, and suggest ways to be successful in brewing and blending a kriek in both homebrew and commercial settings.

Understanding Oude Kriek

So before we get into the nitty-gritty of creating these awesome beers, I would like to throw a personal viewpoint out there: When we think about brewing our own sour beers, there is essentially no limit to how creative you could be in your recipe formulation, blending, and additions of fruits, spices, or other fermentables. American brewers and homebrewers are beginning to consistently produce amazing sour beers. Despite this, there are virtually no American examples of lambic style kriek that can stand shoulder to shoulder with the oude krieks being produced in Belgium. I think there may be a number of reasons for this, but I also know that if brewers truly want to go for it, they can absolutely produce beers that will rival those of the Belgian masters. It is my goal to teach you how.

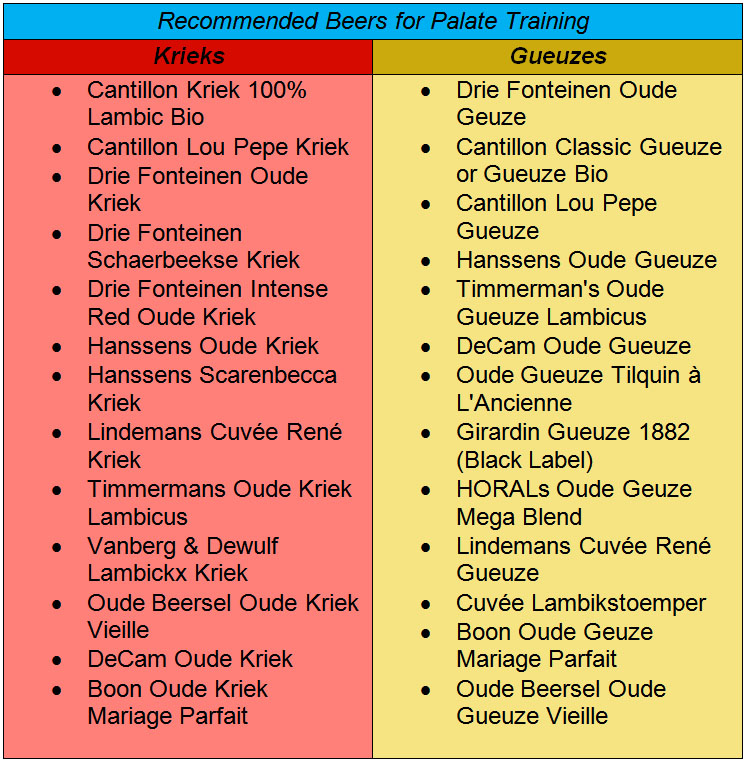

The first step to producing world class krieks is to find would class krieks, drink them, and learn what they taste like. You’re going to need to drink a lot of them, and in quantities larger than the one ounce pours that occur when a dozen friends split a bottle of Cantillon. Make it your goal to find and drink excellent krieks from a variety of producers and of a variety of vintages. You will quickly develop a sense for the parameters of the style, what is allowed and not allowed. You will learn when a bottle hasn’t aged or developed properly, which sometimes happens, even from expert producers. You will also learn when a blend is on-point, and begin to select what flavors you would like your krieks to portray. Without this knowledge you won’t know if your base beers are on the right track. Additionally, you will need to familiarize yourself with world class gueuzes as well. This is because before cherries are added, the base beer for a kriek has more in common with a gueuze than with any other style. I have compiled a list of krieks and gueuzes that I recommend you taste. Some of these beers will be difficult to find, and you don’t need to find every single one, but don’t underestimate the importance of this. Krieks are a blended sour beer. They cannot be produced without a trained palate. So, with palate training in mind, let’s talk about what to expect in a classic lambic oude kriek…

The first step to producing world class krieks is to find would class krieks, drink them, and learn what they taste like. You’re going to need to drink a lot of them, and in quantities larger than the one ounce pours that occur when a dozen friends split a bottle of Cantillon. Make it your goal to find and drink excellent krieks from a variety of producers and of a variety of vintages. You will quickly develop a sense for the parameters of the style, what is allowed and not allowed. You will learn when a bottle hasn’t aged or developed properly, which sometimes happens, even from expert producers. You will also learn when a blend is on-point, and begin to select what flavors you would like your krieks to portray. Without this knowledge you won’t know if your base beers are on the right track. Additionally, you will need to familiarize yourself with world class gueuzes as well. This is because before cherries are added, the base beer for a kriek has more in common with a gueuze than with any other style. I have compiled a list of krieks and gueuzes that I recommend you taste. Some of these beers will be difficult to find, and you don’t need to find every single one, but don’t underestimate the importance of this. Krieks are a blended sour beer. They cannot be produced without a trained palate. So, with palate training in mind, let’s talk about what to expect in a classic lambic oude kriek…

A lambic style (oude) kriek will have an ABV between 4.5% to 6.5%, although being somewhat lower or higher than this is acceptable. The alcohol presence in a kriek should be completely transparent. It is never appropriate for the style to taste boozy, hot, or solventy. The body will be light to medium light with a high level of carbonation. While the body may be light and the final gravity should be attenuated to complete dryness (sometimes below 1.000), the mouthfeel should be medium due to an interplay between the complex flavors, tannins, and carbonation. Cherries should dominate the aroma and flavor of freshly blended krieks, although as they age the Brettanomyces characteristics can become more intense than the fruit. For the purpose of this article, I would consider any kriek that has aged up to about one year in the bottle to be freshly blended. The sourness in a freshly blended kriek is classically balanced to be about the same intensity as that of fresh sour cherries. Despite this generalization, it is acceptable to range from lightly tart to bracingly sour as long as this sour profile is almost entirely composed of lactic acid and natural fruit acidity from the cherries. A freshly blended kriek should not have any detectable vinegar character. As krieks age for several years they may develop light acetic notes, but while this may be tolerable, even with age vinegar is not generally desirable. Krieks should have a dry wine-like finish that leaves your palate refreshed. It is acceptable and, in some cases, desirable for a kriek to have some light to medium tannic content. These tannins provide complexity and body as well as crispness to the finish. The tannin content should not taste overly sharp or astringent.

A kriek may range in color from ruby or crimson to the deepest of maroons bordering on black. The amount of real fruit used to produce true lambic style krieks will be enough to prevent them from being any lighter in color than this, like many pinkish hued American sour beers which use less fruit. It is preferable for these beers to be fairly clear, although hazy blends are traditionally fine as well. The individual cherry crop, specific varietals used, and processing of the cherries will impact the flavors imparted to a blend. The goal in adding the fruit should be to achieve a cherry character that tastes natural. The fruit flavor may range from that of fresh cherry juice, to pie-filling or cherry jam, to the flavors of cherry wine. The medicinal flavors of cherry cough drops, or artificial flavors like those of cherry coke are not desirable or appropriate. Additionally, authentic krieks will not exhibit any artificial spice flavors such as cinnamon. One of the components unique to this style is a distinct almond flavor that comes from the pits of whole cherries as they age in the base lambic. This flavor can range anywhere from mild to intense, but a complete absence of it would indicate that pitted cherries were used in the blend, and this would not be traditional. Additionally, lambic style krieks may exhibit some light to moderate vanilla flavor and aroma, which is a product of their oak aging.

A kriek may range in color from ruby or crimson to the deepest of maroons bordering on black. The amount of real fruit used to produce true lambic style krieks will be enough to prevent them from being any lighter in color than this, like many pinkish hued American sour beers which use less fruit. It is preferable for these beers to be fairly clear, although hazy blends are traditionally fine as well. The individual cherry crop, specific varietals used, and processing of the cherries will impact the flavors imparted to a blend. The goal in adding the fruit should be to achieve a cherry character that tastes natural. The fruit flavor may range from that of fresh cherry juice, to pie-filling or cherry jam, to the flavors of cherry wine. The medicinal flavors of cherry cough drops, or artificial flavors like those of cherry coke are not desirable or appropriate. Additionally, authentic krieks will not exhibit any artificial spice flavors such as cinnamon. One of the components unique to this style is a distinct almond flavor that comes from the pits of whole cherries as they age in the base lambic. This flavor can range anywhere from mild to intense, but a complete absence of it would indicate that pitted cherries were used in the blend, and this would not be traditional. Additionally, lambic style krieks may exhibit some light to moderate vanilla flavor and aroma, which is a product of their oak aging.

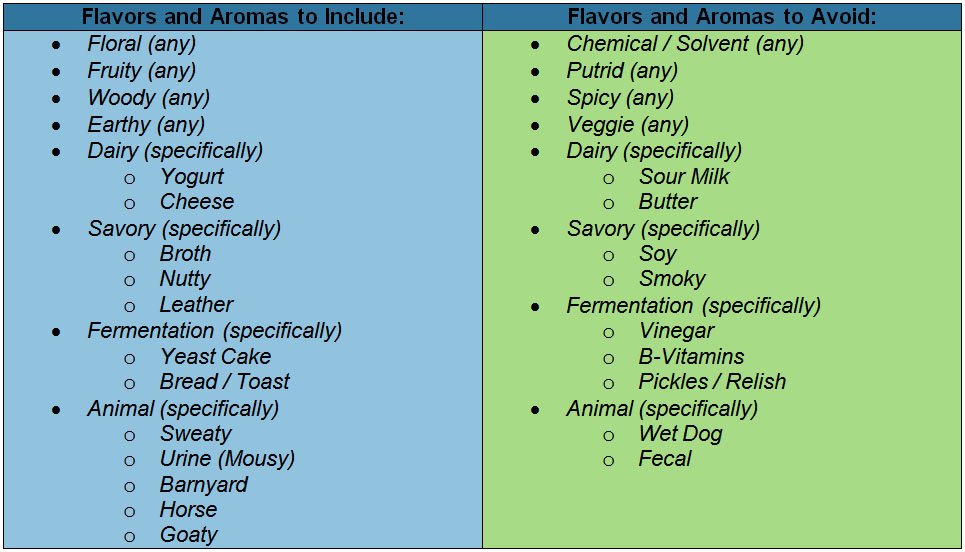

Krieks exhibit a wide variety of Brettanomyces character of varying levels of intensity. The nature and intensity of “funk” in these beers is one of the key components that differentiates the house flavors of different lambic brewers and blenders. When thinking of sour beer flavors, we typically attribute all the funky aromas and flavors as being the products of Brettanomyces, which the majority are. However, in lambics and other spontaneously fermented beers, this is not always the case. There are numerous potential organisms which affect the flavor profile of lambic beers including Enterobacter, Kloeckera, Candida, and wild strains of Saccharomyces. Despite the unpredictability of spontaneous fermentation, there is a realm of flavors which are appropriate or acceptable in kriek and a number of potential fermentation derived flavors that should not appear in the style. I have produced lists of these flavors which you should reference when tasting your base beers before including them in a blend. While I personally feel that the best krieks exhibit medium to high levels of Brettanomyces character, it is acceptable within the style to produce a blend with low levels of funk as long as some Brett presence is evident.

Krieks exhibit a wide variety of Brettanomyces character of varying levels of intensity. The nature and intensity of “funk” in these beers is one of the key components that differentiates the house flavors of different lambic brewers and blenders. When thinking of sour beer flavors, we typically attribute all the funky aromas and flavors as being the products of Brettanomyces, which the majority are. However, in lambics and other spontaneously fermented beers, this is not always the case. There are numerous potential organisms which affect the flavor profile of lambic beers including Enterobacter, Kloeckera, Candida, and wild strains of Saccharomyces. Despite the unpredictability of spontaneous fermentation, there is a realm of flavors which are appropriate or acceptable in kriek and a number of potential fermentation derived flavors that should not appear in the style. I have produced lists of these flavors which you should reference when tasting your base beers before including them in a blend. While I personally feel that the best krieks exhibit medium to high levels of Brettanomyces character, it is acceptable within the style to produce a blend with low levels of funk as long as some Brett presence is evident.

When all of these components come together in a well crafted kriek, the result is truly a thing of beauty. I encourage you to read these guidelines when tasting various commercial examples and seek to detect and understand the flavors and characteristics I have described here in real world oude krieks. The art of blending this style is striking a balance between the acidity, fruit aromatics and flavor, and funkier, earthier, Brettanomyces undertones. If you develop a sour brewing program that produces beer with appropriate lactic acidity, some reasonable level of Brett character, and is free of inappropriate yeast character, free of vinegar, nail polish, parmesan cheese, and the aromas of vomit or feces, you have already come much further than many brewers before you. The next steps will be sourcing quality fruit and avoiding mistakes during the handling and aging of your beer. Lets now take a look at ways to produce sour beer appropriate for blending fruit lambics.

Producing Sour Beer

Traditionalists will cite a very specific and rigid process for producing lambic base wort. This is the same process being used at most of the classic lambic breweries today, and when combined with the right blend of microorganisms and the proper handling and aging, this method will produce excellent base lambic. An overview of this process looks like this:

30-40% un-malted wheat is combined with 60-70% malted barley, typically of the Belgian pale or Belgian pilsner variety. These grains are mashed using a process called turbid mashing. Between each temperature step of this “turbid mash” a portion of the liquid runnings are scooped or pumped out of the mash tun and boiled. These boiled portions are added back into the main mash to facilitate the following temperature rests:

- Mash in between 113° to 120° F

- Rise to 136° F

- Rise to 149° F

- Rise to 162° F

- A final infusion of boiling water brings the mash to 170° At this point the mash is sparged into the boil kettle. This sparge may be run off at temperatures higher than 180° F. This process helps increase extract yield and introduces some grain tannins into the wort which do impact the flavor profile later on.

At the beginning of the boil, about 2 lbs per barrel (about 1 ounce per gallon) of aged hops are added. These hops should be noble or other low alpha-acid varieties which have then been oxidized by aging to reduce their bittering potential. Lambic brewers do occasionally include a small portion of fresh hops in their boils, but these are kept to a minimum and are of low-alpha acid varieties. The wort is boiled for around 4 hours and targets an original gravity of 11° to 14° Plato (1.044 to 1.056 specific gravity) before being pumped into the coolship for overnight cooling. This air-inoculated wort is then pumped into a mixing tank and then into barrels to undergo spontaneous fermentation.

For those brewers who like to over-romanticize the hot side of the brewing process, this weird, old-world, mashing and boiling regime sound like a magic recipe for producing high quality lambic beers. When combined with micro-organisms from the air inside lambic breweries, as well as the generationally refined organisms living in those brewery’s barrels, this highly unfermentable wort does, with proper handling, produce excellent lambic beer. However, when combined with laboratory cultures, and less than perfect cellaring practices, this type of wort can be a recipe for disaster in start-up sour brewing programs. The typical problem encountered is that the lab-sourced cultures being used are often less aggressive, and end up taking even longer than expected to sour and attenuate the wort. If barrels are not properly maintained and topped up during this long aging process, the souring that eventually occurs is made up of too much acetic acid and ethyl acetate, leaving the base beer harsh and solventy. Unfortunately for consumers, many of these inferior products still make it to market, because either the brewer doesn’t understand that what he or she is tasting is not appropriate, or because they cannot stand to dump beer that has taken so much time to make.

For those brewers who like to over-romanticize the hot side of the brewing process, this weird, old-world, mashing and boiling regime sound like a magic recipe for producing high quality lambic beers. When combined with micro-organisms from the air inside lambic breweries, as well as the generationally refined organisms living in those brewery’s barrels, this highly unfermentable wort does, with proper handling, produce excellent lambic beer. However, when combined with laboratory cultures, and less than perfect cellaring practices, this type of wort can be a recipe for disaster in start-up sour brewing programs. The typical problem encountered is that the lab-sourced cultures being used are often less aggressive, and end up taking even longer than expected to sour and attenuate the wort. If barrels are not properly maintained and topped up during this long aging process, the souring that eventually occurs is made up of too much acetic acid and ethyl acetate, leaving the base beer harsh and solventy. Unfortunately for consumers, many of these inferior products still make it to market, because either the brewer doesn’t understand that what he or she is tasting is not appropriate, or because they cannot stand to dump beer that has taken so much time to make.

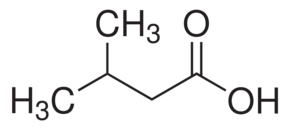

Another process embraced by many American brewers, that in most cases is inappropriate for lambic style blending, is the process of mash or kettle souring. For more details on these processes, check out our review of Fast Souring with Lactobacillus. Also, you may want to check out our articles on brewing Gose & Berliner Weisse, two styles which can benefit from these practices. If conducted in the presence of oxygen, sour mashing or kettle souring can yield a number of aerobic bacterial fermentations which compete with the desired anaerobic fermentation of Lactobacillus. These aerobic bacteria can produce acetic acid (vinegar) in this early stage of fermentation and this off-flavor will not age out of a beer. Additionally, if these processes are not held at the correct temperatures (between 112° and 120° F) and below a pH of 4.7, anaerobic bacteria of the Clostridium & Streptococcus families can produce a number of by-products including butyric acid (rancid milk, vomit) and isovaleric acid (parmesan cheese, stinky feet). Lastly, if the pH of the souring wort or mash is above 4.5, Enterobacter such as E. coli can dominate the fermentation, producing aromas of fecal matter and potentially producing toxic substances.

Two potential wort production and fermentation processes that are likely to yield success when producing base beer for lambic style blending are as follows:

Option A – Pitching all your microbes together.

- Produce a wort using 30-40% malted wheat and 60-70% malted barley of the pale or pilsner variety. This grain should be mashed using a step or single infusion process to yield a wort of moderate fermentability, using a saccharification rest between 152° to 156° F

- Sparge as normal or at temperatures slightly higher than 180° F if additional tannin content is desired.

- Boil without hops or add aged hops at a rate of up to one ounce per gallon. If fresh noble hops are used keep the IBUs of the wort under 15. Boil for 60 minutes if using pale malt and 90 minutes if using pilsner.

- Target an original gravity of 11° to 14° Plato (1.044 to 1.056 SG)

- Cool to approximately 65° to 70° F

- Transfer into a fermentation vessel and oxygenate as usual.

- Pitch a mixed culture including Saccharomyces, Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, and Brettanomyces. Addition of dregs from freshly blended lambics may reduce time to maturation and help boost complexity. Ferment and age this beer at 60° to 70° F

- After initial fermentation has subsided, the beer may be racked off of yeast sediment into an aging vessel or barrel if you desire to limit potential earthy, meaty, flavors than can occur from the autolysis of dying Saccharomyces. Keep in mind that this autolysis can continue to feed Brettanomyces and some degree of it encourages more of the dirty, earthy, variety of funk. At this point and during all future aging and transfers, oxygen is enemy # 1 to your beer. Avoid its pickup at every step. If using barrels for aging, maintain some fermented beer in stainless steel to top up the barrels as losses to evaporation will occur.

Beer made using this process will generally reach a flavor profile which is favorable for using in blends anywhere from 6 months to 2 years from the time it is produced.

Option B – Using Staggered Pitching of Microbes to Enhance Predictability (The Sour Program I Personally Use).

This option uses all the same recipe, boiling, and aging components.

- With this method you can target a mash saccharification rest as low as 145° F or as high as 160° F depending on the length of aging time and flavor goals.

- After boiling, cool the wort to between 110° to 120° F and run into a primary fermentation vessel. At these temperatures you must be using stainless, plastic, or wood for primary fermentation. Do not run hot wort into glass carboys!

- Pitch a culture of Lactobacillus and, if possible, hold the fermentation temperature between 112 to 120° F for between 2 to 4 days. Make sure to purge all oxygen from the fermentation vessel and maintain the utmost cleanliness and sanitation. If wild yeast begins to ferment at this step your results will most likely need to be dumped.

- After 2 to 4 days, cool the vessel to 65° F, oxygenate, and pitch an active culture of Saccharomyces.

- After all potential attenuation by Saccharomyces, transfer (avoiding oxygen) to an aging vessel and pitch a single or mixed culture of Brettanomyces. If desired, at this point add Pediococcus as well and any lambic dregs you would like to use.

In my experience, beers made using this stepped fermentation approach develop desired flavors on an accelerated timetable, and will be ready for use in blends anywhere from 2 months to 1 year after initial fermentation.

While these are two options that have been tested many times and produced excellent results in my sour program, each brewer will find their individual circumstances vary and adaptation may be desired or necessary. The keys here are not to over think recipe formulation, rather focus on healthy fermentations using a variety of microbes. Avoid steps in early fermentation that may produce rancid, cheesy, vomit-like, or fecal off flavors. Also avoid any process during late fermentation and aging that introduces oxygen, as this will inevitably lead to vinegar or solvent off-flavors. When using laboratory cultures with or without bottle dregs, it pays to vary the source of the cultures and specific strains being used from batch to batch. This will help to introduce flavor variety into your base beers that will become crucial during blending. The introduction of flavor variety would also be a reason to experiment with wild collected microbes from spontaneously fermented starter cultures. While starters left to sit out and collect microbes are very unlikely to produce excellent beers on their own, their addition during the aging step of either of the above processes can yield additional flavor complexity and positive results. Make sure to keep detailed notes on your processes and cultures, specifically when using lab-sourced microbes, as these will help you to recreate base beers which achieved specific desirable characteristics again when needed.

Now that we’ve got a process set up to create base beer, let’s talk about designing a blending program.

Setting Up A Blending Program

Implementing a process that produces high quality base beer is a key step in any sour brewing program. The next step is to stop thinking about beer as a straight-line process that starts with a recipe and ends with a delicious beverage in your glass. While great sour beers can be made using the traditional concept of recipe → brewing → fermenting → packaging → serving, lambic style beers and krieks embody a complexity of flavor that no single fermentation can achieve. The way I think about my sour brewing program is as follows… Base beers are brewed on a regular schedule to put into the program. These beers age for some amount of time until a number of them feature flavor components that I would like to use in a blend. Portions of varying batches are selected from time to time to produce a blend. This blend then receives an addition of fruit and undergoes another round of fermentation. When this beer has once again fully attenuated and tastes right, it is bottled or kegged for serving. In this process beers go into the program, and eventually beers come out of the program, but there is no clear line between the two. Some batches may be pulled out for use in other projects such as producing dry-hopped sour blondes, or some batches may develop off-flavors and get dumped.

Implementing a process that produces high quality base beer is a key step in any sour brewing program. The next step is to stop thinking about beer as a straight-line process that starts with a recipe and ends with a delicious beverage in your glass. While great sour beers can be made using the traditional concept of recipe → brewing → fermenting → packaging → serving, lambic style beers and krieks embody a complexity of flavor that no single fermentation can achieve. The way I think about my sour brewing program is as follows… Base beers are brewed on a regular schedule to put into the program. These beers age for some amount of time until a number of them feature flavor components that I would like to use in a blend. Portions of varying batches are selected from time to time to produce a blend. This blend then receives an addition of fruit and undergoes another round of fermentation. When this beer has once again fully attenuated and tastes right, it is bottled or kegged for serving. In this process beers go into the program, and eventually beers come out of the program, but there is no clear line between the two. Some batches may be pulled out for use in other projects such as producing dry-hopped sour blondes, or some batches may develop off-flavors and get dumped.

To some degree this may seem haphazard, and in reality there are components that are out of our control. Despite this, if proper brewing, fermenting, and cellaring practices are maintained, you will have quality beer going into the program and quality beer coming out. A fully developed sour brewing and blending program is the only method that can be expected to recreate lambic style gueuze or kriek. For true lovers of the style, the krieks you will be able to produce will be more than worth the materials and time invested.

So you’ve laid the groundwork and invested the time to produce high quality base beers, now it’s time to actually blend a kriek!

Blending a Lambic Style Oude Kriek

This is the point at which all of the money and time spent hunting down and drinking world-class examples of kriek and gueuze will pay off. Some brewers make the mistake of believing that all lambic products are created by blending equal parts of one, two, and three year old unblended lambic. The reality is that these beers are blended completely by taste, regardless of their age. While it is true that a typical gueuze contains about 60% one-year lambic, 30% two-year lambic, and 10% three-year lambic, these are guidelines not rules. Products such as Cantillon’s Lou Pepe Gueuze, Kriek, and Framboise are all blended from 100% two-year lambic. These products are also blended from barrels exhibiting above average flavor profiles.

Classically, most blenders use a majority of 1 year lambic for their kriek blends. There are two reasons for this. The first is that while Brettanomyces character is important for the style, it is not typical to produce a blend where the Brettanomyces funk outshines the cherries used in the blend. The second reason for this is because cherries do not contain any complex sugars, so their addition to the beer will increase the overall degree of attenuation, leaving less residual long chain sugars behind per volume to produce refermentation and carbonation during traditional lambic bottle conditioning. From a flavor standpoint, if you want to produce krieks that are similar to most young bottled examples you will shoot for a blend of base beers with a moderate acidity, about that of unsweetened lemonade, and a moderate level of Brettanomyces character. Of course, at this point you will understand the flavors involved and are free to be a little creative as well. The kriek you produce can vary significantly in acidity and funk while still being considered an excellent example of the style.

Classically, most blenders use a majority of 1 year lambic for their kriek blends. There are two reasons for this. The first is that while Brettanomyces character is important for the style, it is not typical to produce a blend where the Brettanomyces funk outshines the cherries used in the blend. The second reason for this is because cherries do not contain any complex sugars, so their addition to the beer will increase the overall degree of attenuation, leaving less residual long chain sugars behind per volume to produce refermentation and carbonation during traditional lambic bottle conditioning. From a flavor standpoint, if you want to produce krieks that are similar to most young bottled examples you will shoot for a blend of base beers with a moderate acidity, about that of unsweetened lemonade, and a moderate level of Brettanomyces character. Of course, at this point you will understand the flavors involved and are free to be a little creative as well. The kriek you produce can vary significantly in acidity and funk while still being considered an excellent example of the style.

The palate training you have provided yourself will help you to taste and analyze your base beers for several key components:

- Perceived Sourness

- Brettanomyces Character

- Body, Mouthfeel, Tannin Content, and Attenuation

- Presence of Off-Flavors

Lets discuss each of these characteristics in more detail.

Perceived Sourness

The souring level of your base beer will be a function of how much lactic acid has been produced by bacteria of the Lactobacilli and Pediococci families. This sourness is something to consider completely independently of the beer’s “funk”. You can measure the acid content of a base beer numerically with a pH meter, but I feel this is more useful when trying to reproduce a specific base beer rather than having any merit in the blending process. When it comes to blending, taste is the bottom line. Some beers may develop such an intense sourness that they themselves are undrinkable. However, as long as this is a clean lactic souring and not a harsh vinegar/solvent souring, these beers can be very useful in boosting the acidity of a blend incorporating several less sour additions.

Brettanomyces Character

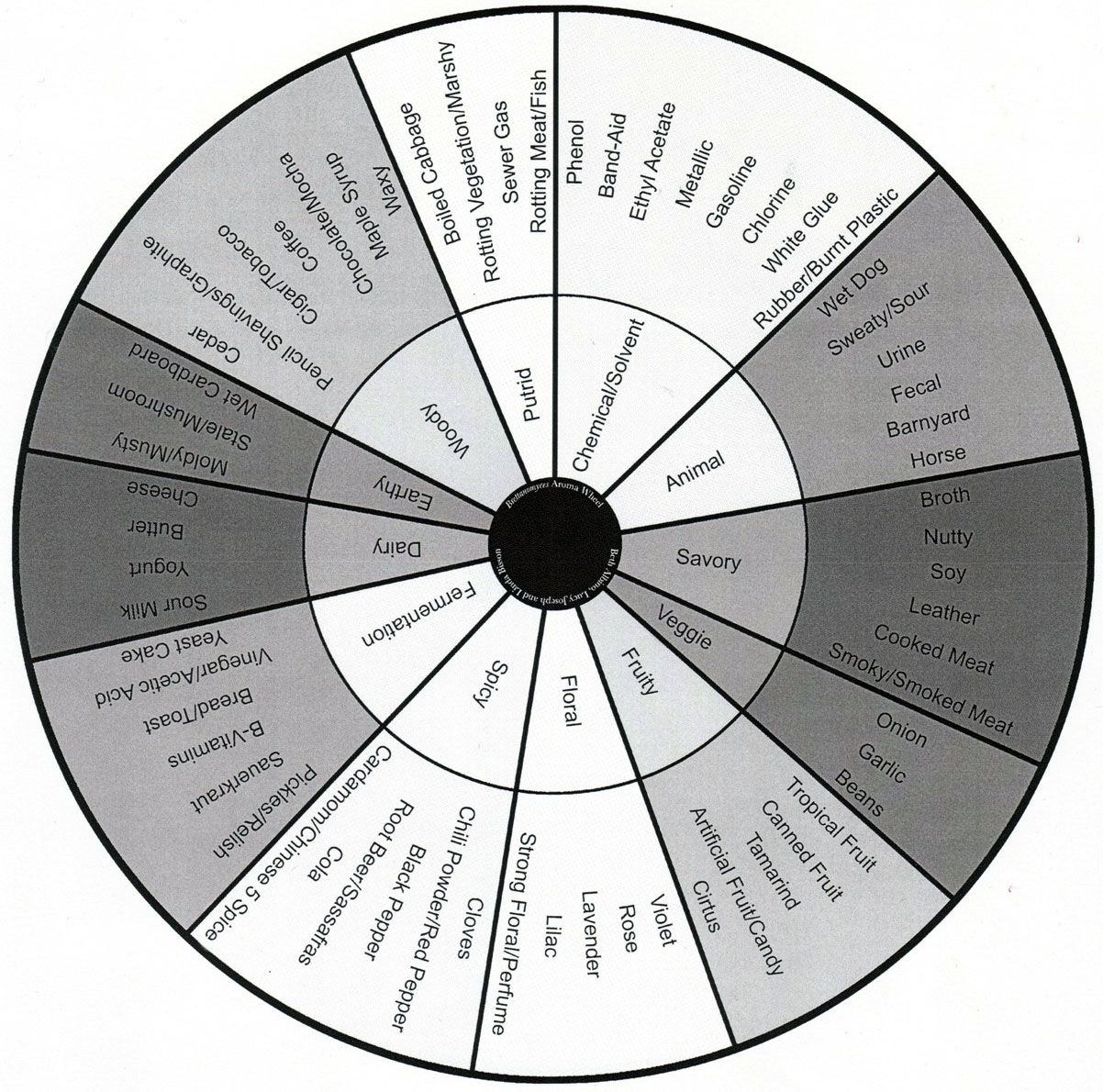

Different strains of Brettanomyces, and the environment to which they are exposed, are the single most variable producer of flavor and aroma in sour beer. Generally speaking, one strain in a specific environment (a single base beer), will not produce the wide bouquet of flavors and aromas that exist in lambic beers. Once again, blending is the key to taking beers with a variety of individual Brettanomyces characteristics and combining them into a single product with a complex profile. I have posted a copy of the Brettanomyces Aroma Wheel, produced by Dr. Linda Bisson and Lucy Joseph at UC Davis, to help you evaluate the Brettanomyces characteristics in your base beers. In general you will be looking to use beers with characteristics listed in the column to the left, while avoiding beers that exhibit a strong presence of characteristics in the column to the right.

Keep in mind that you shouldn’t expect to have beers that showcase all of these aspects. As I noted earlier, the specific blend of these flavors and aromas is related to both the development of house character between lambic brewers and blenders as well as important to distinguishing different blends from one another, such as the variation seen within Drie Fonteinen’s Armand 4 Seasons Gueuze Series.

Body, Mouthfeel, Tannin Content, and Attenuation

When blending, it is important to keep a goal in mind as to the overall character of the blend you are aiming for. Situations may arise where you produce an excellently flavored beer that is lacking in body or mouthfeel. Additionally, a blend may be over or under attenuated, or have too much or too little tannin content. Situations like this showcase the benefit of introducing a few variation recipes into your program. Beers purposely brewed with higher protein content (something that could be achieved by adding oats to a recipe) or brewed to be higher in tannin content (achieved through more oak contact or a hotter sparge) can be useful tools to have on hand when blending. Beers such as this may be purposely fermented with a goal to achieve moderate acidity and funk so that they may be included in blends without significantly altering the overall flavor profile.

Avoiding Off-Flavors

A world-class beer can be reduced to mediocrity or even a drain pour with the inclusion of a significant off-flavor during the blending process. It is far better to dump batches that contain strong off-flavors than risk ruining the contributions of all of your other good batches. The previous table contained a number of Brettanomyces derived off-flavors that may, at times, be unpredictable or dependent on the individual strains you are using. The following are off-flavors that arise from flaws in the brewing, fermentation, or aging process. Steps should be taken to avoid producing these flavors, and if they arise, the beers containing them should not be used in your blends.

Butyric Acid (vomit, bile, rancid milk) & Isovaleric Acid (parmesan cheese, stinky feet)

These organic acids are produced by strains of both aerobic (oxygen loving) and anaerobic bacteria that can reproduce in a fermentation when not enough yeast is present to begin reducing the pH and increasing the alcohol content of the wort. These tend to occur most frequently during sour mash or sour kettle procedures. They could also occur during a Lactobacillus only fermentation if proper sanitation and closed transfer practices are not followed. They can generally be avoided by scrubbing the wort with CO2, keeping the wort in a completely anaerobic environment, beginning fermentation with a wort pH below 4.7, and maintaining a temperature above 112° F during Lactobacillus only fermentation steps. If they occur at a mild level early on they may be converted to flavor neutral or flavor positive compounds by Brettanomyces. However, if they are nauseatingly present when pitching primary yeast cultures, it is better to save your efforts and dump the batch before pitching.

Acetic Acid (vinegar) and Ethyl Acetate (solvent, nail polish remover)

In the presence of oxygen, the bacteria Acetobacter and the yeast Brettanomyces can metabolize alcohol into acetic acid. Acetobacter, which thrives at warm temperatures (above 70° F), can do this to an entire batch of beer in a matter of days, while Brettanomyces takes somewhat longer. Additionally, once acetic acid is formed Brettanomyces can metabolize it into ethyl acetate. Acetobacter can be avoided through proper cleaning and sanitation, as well as by reducing or eliminating sources of fruit flies around aging beer. Brettanomyces on the other hand is an integral part of our beer, so the real key here is avoiding oxygen at all times after primary fermentation. If you have ever left a bit of gueuze or kriek sit in a glass overnight, you may have noticed how shockingly vinegary it smelled the next day. This is because after surviving in the bottled lambic, with no sugar and almost no other nutrients to live on, the Brettanomyces is practically “screaming” for life. At this point (and any time late in the aging process), the Brett will rapidly utilize any oxygen that leaks into the beer to produce vinegar.

Chemically, there will be a tiny portion of vinegar and ethyl acetate in any lambic base beer. At these levels the vinegar adds complexity and the ethyl acetate actually tastes like pears. However, any level that is strong enough to taste a distinct vinegary character (especially when this character is stronger than the softer lactic acidity) would be considered a flaw. Additionally, any level of ethyl acetate that can be detected as nail polish remover is too much. A classic example of this is Hanssens’ Oude Gueuze, which walks a fine line with both of these chemicals. In freshly blended and properly cellared examples, a low level of vinegar and slightly higher level of ethyl acetate add a distinctive sharpness to the acidity of the beer. However, if bottles are stored upright for too long and further oxygen leaks in, these blends can become harsh.

Chemically, there will be a tiny portion of vinegar and ethyl acetate in any lambic base beer. At these levels the vinegar adds complexity and the ethyl acetate actually tastes like pears. However, any level that is strong enough to taste a distinct vinegary character (especially when this character is stronger than the softer lactic acidity) would be considered a flaw. Additionally, any level of ethyl acetate that can be detected as nail polish remover is too much. A classic example of this is Hanssens’ Oude Gueuze, which walks a fine line with both of these chemicals. In freshly blended and properly cellared examples, a low level of vinegar and slightly higher level of ethyl acetate add a distinctive sharpness to the acidity of the beer. However, if bottles are stored upright for too long and further oxygen leaks in, these blends can become harsh.

Avoid oxygen pickup during aging by keeping stainless or glass vessels filled up and well sealed. When barrel aging, make sure to top up barrels regularly and immediately repair any leaking barrels. Additionally, make sure to transfer any beer under a blanket of CO2, which is heavier than oxygen and will keep your beer protected from it. At times when oxygen pickup may be boosted by the addition of fruit or oak, it is okay to help scrub it out by running CO2 through a sintered stone placed into the beer for several minutes.

Acetone and Fusel Alcohols / Oils

These chemicals can also taste solventy or warming to the throat. The alcohol presence in a properly blended kriek should never be harsh or warming. These can be produced by Brettanomyces or Saccharomyces during primary fermentation if the yeasts are under pitched or fermented too warm (above 72° F for most Saccharomyces strains and above 80° F for Brettanomyces). Fermentation temperature control is one of the keys to making excellent clean beers such as pale ales and pilsners, and it is no less important during sour beer fermentation. This is one of the main reasons why traditional lambic breweries cease wort production during the summer months of the year.

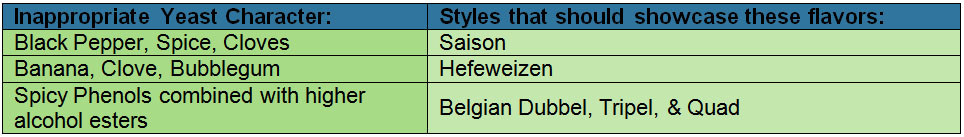

Undesirable Saccharomyces Flavors and Barrel-Aged Characteristics

The last category of off-flavors I will highlight here are flavors which are pleasant and to be expected in other styles of beer, but are not appropriate for a kriek or gueuze. Most of these should be avoided by proper Saccharomyces strain selection. When using laboratory cultures, some of my favorite brewer’s yeast strains are those with clean and neutral flavor profiles or those that produce fruity esters. Strains that are especially spicy or phenolic can boost Brettanomyces flavor development, but sometimes these strains go too far and produce more flavor compounds than Brettanomyces will convert.

I would especially like to point out here that lambic style krieks should not taste like other non-lambic styles originating in Belgium. I have seen many examples by American brewers of Saisons or Belgian Strong Ales being blended with cherries and then labeled as Kriek. These are not representations of the style which we are trying to produce. Additionally, some excellent Flanders Red Ales are produced with cherries blended into them. These have too much oak and vinegar character to be considered lambic style krieks. Additionally, these examples lack the necessary Brettanomyces character required.

The last off-flavor I would like to highlight is bourbon character from oak aging. Like white wines, krieks may showcase some neutral wood flavor and even some light to medium vanillin notes from their time in oak. However, it is inappropriate for the style to have whiskey or bourbon-like oak character. This can be avoided when homebrewing by using lighter toast oak, limiting the amount used, as well as limiting the contact time. On a commercial scale, if aging the base beer in barrels, the barrels should either be recycled from the wine industry or have had several batches of clean beer pass through them to strip out the character from reused spirits barrels.

Ultimately, the goal in blending your base beer is to produce a gueuze-like beer that could be carbonated and served on its own if you desired. Once you have blended an excellent base beer, the most difficult parts are over. From this point you must maintain proper transferring practices in order to avoid oxygen pickup and select a quality variety of sour cherry to add to the beer.

Selecting Sour Cherries and Finishing a Kriek

According to Jef Van den Steen, in his excellent book Geuze & Kriek, the earliest recorded mention of a kriek recipe was in the 1878 manuscript of a Belgian farmer. This recipe called for the addition of 20 kilograms of fresh home-grown cherries to be added to 100 liters of two-year old lambic. These cherries would be harvested in early summer, being added to the beer shortly after harvest. The original recipe from the farmer’s manuscript goes on to add that the lambic should remain on the cherries until December, in other words, for about 5 to 6 months.

The earliest krieks produced in Belgium made use of an heirloom cultivar of dark red sour cherry called Schaerbeek cherries. In modern times, this cultivar has become exceedingly rare agriculturally and has been replaced in almost all kriek blends with other strains of European Morello cherries or in some cases North-American Tart Black cherries. There are a few blends occasionally produced which still use 100% Schaerbeek cherries. These include Hanssens’ Scarenbecca Kriek and Drie Fonteinen’s Schaerbeekse Kriek.

For American brewers, access to Morello cherries will be unavailable or prohibitively expensive. However, there are excellent strains of sour red and black cherries being grown in the states as well. To this extent your taste will be your guide. Select fruit that is delicious and you will produce excellent results with it. If you can find the fruit fresh and locally that is all the better, but if not, there are orchards which will ship high quality frozen cherries through the mail. Frozen sour cherries will typically be pitted, so if you want to produce the authentic almond flavors from cherry pits in your blend, you will need to add these back in separately. I have produced very good results using frozen sour cherries and the pits extracted from fresh sweet cherries. Avoid the use of supermarket varieties of sweet cherries. While these are tasty to eat, they provide far less flavor per volume than tart cherries, and will leave a kriek blend tasting lackluster in the fruit department.

If we are to follow our farmer’s original recipe, the cherries would be added at a rate of 1.75 lbs per gallon of beer. However, most modern lambic blenders are using a rate of 25% cherries by weight, which equates to slightly above 2 lbs per gallon. As a blender, you can use more cherries if you desire. One notable kriek, Drie Fonteinen’s Intense Red Oude Kriek, uses 40% cherries by weight which equates to 3.3 lbs per gallon. As the percentage of cherries used increases, the more wine-like character your kriek will portray. Ultimately, your palate will once again be your guide. Some varieties of cherries will add more character while others will add less. Using 2 lbs of whole crushed sour cherries per gallon is a good starting point.

Once the cherries are added, the Brettanomyces in your base beer will wake back up and ferment the cherry’s simple sugars into alcohol. If you are keeping detailed notes on the homebrew or commercial scale, you can test the original gravity of the cherry juice to estimate its contribution to the blend’s alcohol content. In about one to three months, you can taste the blend and decide whether more cherries are needed. When using base beer fermented in barrels, it is best to both blend the beers and add the cherries in a stainless steel vessel. This method reduces any further oxygen pickup in the barrels, keeps fruit out of your oak, and allows for easier transfer and filtering of fruit solids when it is time to package the beer. Additionally this is the method employed by many of the excellent Belgian brewers and blenders including Cantillon and Drie Fonteinen.

Once the cherries are added, the Brettanomyces in your base beer will wake back up and ferment the cherry’s simple sugars into alcohol. If you are keeping detailed notes on the homebrew or commercial scale, you can test the original gravity of the cherry juice to estimate its contribution to the blend’s alcohol content. In about one to three months, you can taste the blend and decide whether more cherries are needed. When using base beer fermented in barrels, it is best to both blend the beers and add the cherries in a stainless steel vessel. This method reduces any further oxygen pickup in the barrels, keeps fruit out of your oak, and allows for easier transfer and filtering of fruit solids when it is time to package the beer. Additionally this is the method employed by many of the excellent Belgian brewers and blenders including Cantillon and Drie Fonteinen.

When it comes time to package your beer, there are several options available. Traditionally, lambic krieks are bottle conditioned for several months before being served. The fermentable sugar for bottle conditioning comes from either the blending in of a portion of young lambic beer which has not fully attenuated, or from the addition of simple sugar syrup into the beer. When making calculations for these additions, you are aiming for fairly high levels of carbonation, generally from 2.4 to 3.0 volumes of CO2. I highly recommend checking out Michael Tonsmeire’s American Sour Beers for equations and information on how to bottle condition your krieks using young sour beer. While these methods are traditional, there is no evidence to suggest that they produce any better flavor profiles in the packaged beer than force carbonating and serving on draft or in counter-pressure filled bottles. Both methods will produce excellent results when done properly.

When it comes time to package your beer, there are several options available. Traditionally, lambic krieks are bottle conditioned for several months before being served. The fermentable sugar for bottle conditioning comes from either the blending in of a portion of young lambic beer which has not fully attenuated, or from the addition of simple sugar syrup into the beer. When making calculations for these additions, you are aiming for fairly high levels of carbonation, generally from 2.4 to 3.0 volumes of CO2. I highly recommend checking out Michael Tonsmeire’s American Sour Beers for equations and information on how to bottle condition your krieks using young sour beer. While these methods are traditional, there is no evidence to suggest that they produce any better flavor profiles in the packaged beer than force carbonating and serving on draft or in counter-pressure filled bottles. Both methods will produce excellent results when done properly.

Ending Thoughts

It is my sincere hope that this article helps brewers interested in producing lambic style krieks to more successfully do so. Additionally, I hope to inspire brewers who never thought that it would be possible to produce such a beer to try their hand at this wonderful style. For the purists, I want to make it clear that I do not, in any way, intend to diminish or downplay the skill, art, and hard work of the amazing gueuze and kriek blenders of Belgium such as Jean Van Roy, Armand Debelder, Frank Boon, Sidy and John Matthys, Karel Goddeau, Pierre Tilquin, and countless others throughout the ages who have not only carried this traditional beer style through history, but have also made it relevant today. These men and women are, without a doubt, masters of their craft. I personally have an almost “fan-boy” admiration for them and the delicious beers that they produce. I am reminded of Sir Isaac Newton’s famous quote, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants”.

Throughout this article, I have tried to emphasize the importance of developing a palate for these beers. Blending of beers is an art and a skill and your taste buds will be your most important tool. With a bit of planning and understanding, the microbes that we tend to will provide us with the paints for our palettes, it is our job as artists to use these to produce our artwork. Good luck!

-Matthew Miller, Pharm.D.

References

Guinard, Jean-Xavier. Lambic. Boulder, CO, USA: Brewers Publications, 1990. Print.

Ives, Martyn. “How Beer Saved the World.” How Beer Saved the World. Discovery. 30 Jan. 2011. Television.

Katz, Sandor Ellix. The Art of Fermentation: An In-depth Exploration of Essential Concepts and Processes from around the World. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Pub., 2012. Print.

Steen, Jef Van Den. Geuze & Kriek: The Secret of Lambic. Tielt, Belgium: Lannoo, 2011. Print.

Tonsmeire, Michael. American Sour Beers: Innovative Techniques for Mixed Fermentations. Boulder, CO, USA: Brewers Publications, 2014. Print.