Hello Sour Beer Friends!

This past month marked the second anniversary of our first post on Sour Beer Blog! Over these two years, the American sour beer scene has experienced record breaking growth both in the number and quality of sour beers being produced. When creating Sour Beer Blog, one of my goals was to amass a collection of well-informed flavor-based reviews that took into account qualities specific to sour beers. In addition to being useful to consumers, I feel that such reviews can serve as important guides and teaching points for sour brewers looking to hone their palates. However, one of the things that I had not expected was the fantastic response and readership that our brewing and educational articles would receive. With this feedback in mind, myself and the other authors have decided to develop new article formats that will always feature some educational brewing content, even those that also review sour beers! We hope that you will continue to find our content both entertaining and educational, and we look forward to continuing to meet and communicate with all of the wonderful folks in the sour beer brewing community!

Recently, Cale and I had the pleasure to taste two delicious special-release sour beers from Upland Brewing Company of Bloomington, Indiana. We took the opportunity to get in touch with Caleb Staton, the director of sour beer production at Upland, to talk about his sour brewing and barrel aging program as well as the creation of the beers in question, Vinosynth Red and Vinosynth White.

Founded in 1998, Upland Brewing first began experimenting with sour beers in 2006. In Indiana, this was a time when a number of craft beer enthusiasts were interested in the lambics and other sour beers of Belgium, but American sour beer culture and the production of local sours were virtually non-existent. Caleb got started homebrewing after graduating college, later pursuing a formal brewing education from the Master Brewers Program at UC Davis. He joined the Upland team as a Cellarman in 2004 and by 2006 he had been promoted to the position of Head Brewer. It was this year that Caleb and his team traded 8 cases of beer to acquire their first 4 white oak barrels from the nearby Olivery Winery. To fill these barrels, the team researched the lambic production of the Senne Valley and employed techniques such as turbid mashing, using aged hops in a long boil, and fermenting in oak with organisms isolated from traditional lambic beers.

From those first four white oak barrels, Upland’s sour beer program has grown along with a local following and passion for these beers in not only the Bloomington and Indianapolis areas, but nationwide as well. In both 2014 and 2015, they released around 200 bbls of sour beer annually. All Upland sours age for a minimum of 8 months in their barrel program, which at this time contains 150 white oak barrels, 40 bourbon barrels, one 60 bbl foeder, and two 37 bbl foeders. The team produces their wort on a system assembled “Frankenstein style” from equipment from multiple manufacturers at their separate sour brewery. Set up in the location of their original brewpub at the end of 2012, their sour brewing system can produce up to 37 bbls per batch and includes a jacketed mash tun which allows them to reproduce the turbid mashing schemes employed by traditional lambic brewers.

“BBL” is an abbreviation for “barrels”, a unit of volume commonly used in the brewing industry. One bbl is equivalent to 31 U.S. Gallons or approximately 1.17 hectoliters.

Dr. Lambic: What do you like to do for fun?

Caleb: “I enjoy hiking with my dog, building model rockets, and fantasizing about growing fruit trees.”

-Like Extremely

-Like Very Much

-Like Moderately

-Like Slightly

-Neither Like nor Dislike

-Dislike Slightly

-Dislike Moderately

-Dislike Very Much

-Dislike Extremely

Dr. Lambic: When producing Upland Sours, what does your fermentation profile look like?

Caleb: “Initially, we pitched sour blends from Wyeast directly into barrels to kick off the program. These blends contained Saccharomyces, Brettanomyces and other souring microorganisms, which individually go to work at different time periods during their long fermentation. As we grew, we started dedicating an older stainless fermenter to inoculate the wort with a pitch for two weeks before transferring into barrels. Again, allowing each of the various microorganisms to perform their contribution to fermentation in the natural timeframe of contribution. In 2008, we acquired our first foeder, General Sherman, who was also trained by pitching from lab cultures. At this point, after nearly a decade of use, Sherman adds its own character to our beers. It sours more quickly than from a lab pitch alone, and we think this is because the wood in the tank has developed a unique microbial environment. At this point, we only clean Sherman with cold water, and as long as it looks good and smells good, we fill it right back up.”

Caleb (second from the left) and team members Cody (left) and Eli (right) in front of new foeders in the expanding sour brewery with Guillaume (second from right) from Radoux, a French foeder manufacturer.

A robust oak aging program requires an equally robust blending program, which Caleb and his team take very seriously. Their blending process is sensory oriented, with each barrel being tasted individually by a team of 6 participants before it is selected for inclusion in a given blend. Beers are rated using a 9-point Hedonic rating scale, which is one of the most widely studied and accepted rating systems used within the food sciences. After creation, the final blend is confirmed by the team before moving forward to packaging and bottle conditioning. When dealing with the unique and often polarizing flavors that can occur within sour beer, it is important to obtain a wide range of sensory data points. To achieve this, Upland has made use of a focus group made up of 30 individuals who evaluate new fruits, herbs, spices, and yeast blends. Many of these new recipes and blends will be featured in sour beers being released in both 2016 and 2017. These new beers come during an exciting time of expansion for Upland’s sour program. Caleb and his team expect to be able to grow production from 200 to around 2000 bbls per year during the first full year of production.

When it comes to sour beer brewing and blending, I am a huge proponent of sensory analysis. One of the most important things that a sour brewer can do is undergo palate training and use these skills to identify and eliminate off-flavors. When a brewer finds themselves in a position to direct a sour beer production team, establishing a set of quality control standards and creating a culture of quality over quantity is paramount. To this end, I was very interested to learn about Upland’s lab and quality control programs. In addition to operating a full scale lab at their core brewery, Upland is also in the process of building a second lab into their expanding sour brewery. This second lab will be heavily tied into both their sensory program and management of their mixed cultures.

Upland employs both a Quality Manager and a full-time Quality Analyst in their brewing program. Additionally, they are in the process of adding another quality focused role to their staff. The person in this position will be responsible for expanding their sensory program with a strong focus on sour beer blending and assessment. Caleb believes that this role and focus will be key to developing and maintaining consistency as their sour beer program grows. Caleb also discussed sour beer measurement with us, and indicated that their lab actively tracks both gravity and pH throughout fermentation. Additionally, bottles from each packaging run are sent to an outside lab for independent analysis of various specifications including ABV and acidity measurements.

In my opinion, sour beers tend to portray the widest variety of unique flavors and aromas found within any style of beer. These wonderful and interesting characteristics arise from the interplay between multiple genera of both yeast and bacteria. The organisms and mixed cultures that a brewery has at their disposal can dramatically shape the character of the sour beers that are possible within their program. This is why I found it very interesting to learn that Upland has been working with Indiana University to study 7 unique strains of Saccharomyces that the brewery was able to collect from various parts of their home county of Monroe. This study has been working to determine, on a pilot level, what commercial potential these strains may have for both “clean” and sour brewing.

Upland originally sold their sours directly out of their Bloomington location, but as popularity grew they had to quickly adopt a lottery system to cut down on the general craziness that can occur during a limited beer release. Upland also offers annual memberships to their Secret Barrel Society, which gives their biggest fans guaranteed access to sour beer releases before public sale. Additionally, membership comes with some pretty cool swag and tickets to their annual Sour, Wild, and Funk Fest. In 2016, Upland expects to have 4 separate sour bottle releases. The two beers that Cale and I got to enjoy were sold during the first of these events.

Both Vinosynth beers were created as a collaboration between the Upland team and the nearby Oliver Winery, which has supplied Upland with all of their white oak barrels since the formation of their sour program. The Oliver Winery is Indiana’s largest winery (In fact, its one of the largest wineries east of the Mississippi). They began producing wine in the 1960’s and established the Creekbed Vinyard, which supplied both varietals of grape for the Vinosynth blends, in 1994. Vinosynth White was created by blending whole Vidal Blanc grapes with a golden sour beer called Sour Reserve at a rate of 3.75 lbs. per gallon. These were allowed to re-ferment for 3 months before bottling. Vidal Blanc is a winter-hardy hybrid grape developed in France in the 1930’s. It was introduced into the US in the 1940’s and now the majority of its production worldwide occurs here and in Canada. The variety is commonly used to create ice wines and is appreciated for its flavors of pear, apple, honey, pineapple, and grapefruit.

Dr. Lambic: Can you remember the first sour beer that got you interested in brewing these styles?

Caleb: “I always had an appreciation for Belgian-style beers in general, and the some of the wonderful and fruity aspects that the Saccharomyces from the traditional regions impart into the various beer styles. I recall my first American sour ale experience was having a La Folie on draught at the Toronado Pub in San Francisco and I was fascinated by the experience and regard the beer had. That experience probably gave me the confidence as an American brewer to try and replicate traditional lambic and Flanders-style sour ales in a small commercial setting.”

Dr. Lambic: What is your favorite style of sour beer?

Caleb: “Gueuze totally fascinates me, from younger examples to older dust covered bottles. It’s really because that beer is completely naked as far as the malt, hops, microorganisms and water that have been used to fuse them together. And most of the flavors have been derived by the various microorganisms involved in spontaneous fermentation. The art of blending a gueuze is a generational activity, and it is an utterly unique method for beer brewing which tilts toward the artistic side of our industry. Taking multiple years of beer, with various stages in flavor development, and blending them together to create a complex, layered and nuanced beer is absolutely amazing to me. The beer still being alive in the bottle is just the icing on the cake.”

Dr. Lambic: What do you think are the most successful elements of your sour program and what challenges have you encountered? Where would you like to see the program go in the future?

Caleb: “We feel our dedication to developing sour beers through long fermentation in contact with oak has been a successful and challenging aspect simultaneously. We really have to be keen on what the beer is telling us to do rather than trying to force a desired flavor profile. This free-range approach to sour brewing will be more controlled as we grow the program in the new facility. The more batches of sour beer you have access to for blending, the more consistent of a flavor profile can be replicated time after time. Our focus has been very fruit heavy as well, incorporating whole fruit at rates of as much as 3 lbs. per gallon to showcase the flavors and colors we get from them. Our future plans, alongside continuing the beers we currently make, are to develop some new American sour style beers, working more specifically with strains of Brettanomyces, as well as kettle souring methods as part of the beer mix.”

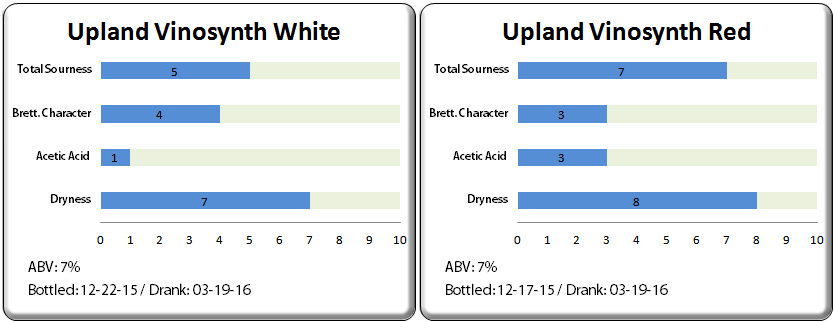

Vinosynth White poured a hazy peach color with a moderate level of white head which disappeared nearly instantly. At the very first sniff, we were taken with the beer’s very mimosa-like aroma profile. These notes of champagne and orange juice were followed up by light stone-fruit, white wine, pears, and vanilla wafer aromas. Later on during the drinking experience, some of the beer’s funkier aspects revealed themselves as the aromas of a lightly musty basement and damp leaves. When tasting Vinosynth White, we were greeted with an assertive but well integrated lactic and malic acidity with the lightest touch of acetic acid also present and offering a bit of complexity. This beer portrayed a pleasant mix of fruit flavors which put us in mind of a Dole mixed-fruit cup with peaches in grape juice. We also picked up flavors of pears and oranges which mirrored the aromas being given-off. The beer was dry, highly carbonated, with a light body and a refreshing finish that highlighted acidity and fruit at the end of each sip. While the beer was well attenuated, its combination of fruit flavors gave the perception that it had quite a bit of balancing sweetness. While both Vinosynth beers boast a 7% ABV, this alcohol presence was completely transparent, an indication to our palates of quality fermentation management on the part of both blends. We would recommend pairing Vinosynth White with a nice cream-based pasta dish such as Chicken Alfredo and a banana nut bread dessert.

Vinosynth White poured a hazy peach color with a moderate level of white head which disappeared nearly instantly. At the very first sniff, we were taken with the beer’s very mimosa-like aroma profile. These notes of champagne and orange juice were followed up by light stone-fruit, white wine, pears, and vanilla wafer aromas. Later on during the drinking experience, some of the beer’s funkier aspects revealed themselves as the aromas of a lightly musty basement and damp leaves. When tasting Vinosynth White, we were greeted with an assertive but well integrated lactic and malic acidity with the lightest touch of acetic acid also present and offering a bit of complexity. This beer portrayed a pleasant mix of fruit flavors which put us in mind of a Dole mixed-fruit cup with peaches in grape juice. We also picked up flavors of pears and oranges which mirrored the aromas being given-off. The beer was dry, highly carbonated, with a light body and a refreshing finish that highlighted acidity and fruit at the end of each sip. While the beer was well attenuated, its combination of fruit flavors gave the perception that it had quite a bit of balancing sweetness. While both Vinosynth beers boast a 7% ABV, this alcohol presence was completely transparent, an indication to our palates of quality fermentation management on the part of both blends. We would recommend pairing Vinosynth White with a nice cream-based pasta dish such as Chicken Alfredo and a banana nut bread dessert.

Vinosynth Red was created by adding fresh whole Catawba grapes into a blend of 50% Sour Reserve, and 50% Malefactor, a sour red brewed in the style of a Flanders Red Ale. Catawba grapes are an American heritage variety with cultivation dating back to the early 1800’s. Frequently used for jams and jellies, Catawba grapes produce distinctively juicy, foxy wines that are pink to rose in color. These grapes are are known for intense fruit character reminiscent of peaches, strawberries, and cotton candy. To account for the intensity of their character, these grapes were added at a lower rate of 2.5 lbs per gallon and, again, allowed to re-ferment for 3 months before bottling.

Vinosynth Red poured a pinkish-red / dark peach color with a medium level of white head that hung around for several minutes. We were greeted with a maltier aroma profile portraying characteristics of caramel, oak, vanilla, and stone-fruits. There were notes of dehydrated dark fruits such as raisins, prunes, and dates, as well as a more generalized fruity sweetness. We also picked up light elements of acetic acid and light sherry notes.

Vinosynth Red poured a pinkish-red / dark peach color with a medium level of white head that hung around for several minutes. We were greeted with a maltier aroma profile portraying characteristics of caramel, oak, vanilla, and stone-fruits. There were notes of dehydrated dark fruits such as raisins, prunes, and dates, as well as a more generalized fruity sweetness. We also picked up light elements of acetic acid and light sherry notes.

When drinking Vinosynth Red, we were greeted with a very soft and well balanced flavor profile. There was none of the sharp acetic acid bite that can come across as harsh in a number of European Flanders Reds. Rather, this beer had a soft and complex blend of acetic, lactic, and malic sourness that melded seamlessly with the beer’s malt profile. An assertive fox-grape fruit character combined with caramel flavors played a counterpart to the well-attenuated, highly carbonated, and light bodied aspects of the beer. Overall, Vinosynth Red took the classic Flanders balance of malt, acid, fruity esters, and oak and upped the fruit ante in a wonderful way. In short, both Cale and I were very happy while drinking this beer! We would recommend pairing Vinosynth Red with a lightly seasoned steak and a chocolate cheesecake for dessert.

Dr. Lambic: What piece of advice would you give a brewer who is preparing to brew their first sour beer?

Caleb: “Be no less attentive to cleanliness than any other brewing activity. Be patient. Record your every step. And lastly, have fun!”

The term “Sherry” gets thrown around quite a bit to indicate oxidation of any amount in a beer. However, it is properly used to describe the actual aroma of Sherry wine, a positive quality in some barrel aged sour beers. This should not be confused with negative aspects of oxidation such as cardboard, wet paper, or wet dog (None of which were present in either of the beers we sampled).

Dr. Lambic: What is one mistake that you would like to see eliminated from, or improved upon, in the current sour beer market?

Caleb: “Fair and accurate pricing based upon the efforts of the brewers, ingredients, and processes involved in sour beers. A kettle soured beer is not the same thing as a wood aged sour beer brewed with pounds of fruit per gallon over a long fermentation period. I appreciate a good Berliner Weisse and Gose, and each style is brewed with a moderately advanced understanding of brewing, however, the lesser cost of ingredients, work, attention, and quick turn around time do not merit a similar price point to other styles of sour beer. Most breweries are embracing this difference whole-heartedly, but the price discrepancy trend could do a lot of damage to this fledgling and exciting part of the craft beer industry.

Another improvement we are implementing is the removal of the term “lambic” from our beer packaging, this is misleading and comes with some disrespect towards the traditional lambic breweries. Our mistake was out of naivety, and I’m glad we’re finally correcting ourselves.”

While Upland’s sour beers have been on my radar for a number of years, this was my first time tasting them and it was a very positive experience. I am definitely looking forward to getting the opportunity to try more of their sour beer creations in the future. Additionally, I was pleased to hear that they are in the process of removing the “Lambic” moniker from their fruited sours out of respect for the Belgian brewers who produce these region-specific beers. If you get the chance to taste either of the Vinosynth blends, don’t miss out! I will certainly be on the lookout for more goodness from Caleb and his team!

Cheers!

Matt “Dr. Lambic” Miller

I would very much like to give a special thanks to both Caleb Staton and Emily Hines from Upland Brewing for their participation with this article.

Dr. Lambic’s Educational Corner: Sour Beer Fruit Additions with Caleb Staton of Upland Brewing

Hello Sour Brewers!

Sour beers offer brewers a fantastic canvas upon which to showcase a nearly limitless variety of delicious fruit flavors. The natural acidity of these beers tends to bring out the brightest, freshest, and juiciest qualities of any particular fruits being used. Given the diverse portfolio of fruited sours produced at Upland, I thought that this topic would be an excellent one to discuss with their head of sour production, Caleb Staton!

When sourcing fruit, what qualities do you look for before purchase?

- When possible, we try to source fruit directly from orchards and growers, especially in Indiana and the surrounding states. Michigan is a large fruit producing state, and we commonly receive cherries and blueberries from across our northern border. I have personally visited King Orchards of Michigan, the Huber Orchard of Indiana, and Heartland Family Farms of Indiana, and really appreciate being able to see the fruit harvest and speak with the folks involved. We inspect any fruit once it arrives here at our doorstep, and eating fruit first thing in the day at the brewery is a shared and welcomed ordeal for the staff.

In what form do you prefer to purchase fruit and how do you process it before addition to your beers?

- We receive both fresh and frozen fruits, always whole. Peaches are destoned by hand before freezing the fruit, and kiwis are peeled by hand as well before freezing. All the fruit is frozen for at least 48 hours before we allow it to thaw before adding to a vessel that beer will be added to. We feel this adds a mild layer of sanitation in handling the fruit, as well as allowing the fruit cell walls to be broken down for better access to the sugars during fermentation.

You mentioned usage rates of up to 3 lbs per gallon, which closely mirrors the upper usage rates for traditional lambic. How do you choose what rates to use? Is it based upon the variety of fruit, or intensity of flavor in a given harvest/delivery, etc?

- We started out attempting to create traditional lambic-style beers, and followed a lot of the procedures we had researched to the “T”. At one point we did start to work with different additions of fruit based on different fruit varietal impacts of color and flavor intensity. We really add an almost absurd amount of fruit, but the rich flavors and colors we end up with are something we enjoy immensely. Today, we are pretty much streamlined on adding 225 lbs. of whole fruit to each 265 L barrel, regardless of the fruit variety. However, we have worked with lesser amounts of fruit rates with success as well, our recent release of Cauldron and Black Raspberry were down in the one pound per gallon range, and that worked out well with our intentions for those two beers.

What type of contact time with the beer do you prefer and how do you decide when enough time has passed?

- Most of the beers spend at least 3 months on the fruit, allowing for fermentation of the fruit sugars and some time to mature. We want the final beer to be relatively dry in nature, and allowing for some settling time in the barrel helps with transfer out of the barrel as well.

When creating a base blend to add fruit into, what types of qualities do you look for / prefer in your base beer?

- We look for a base beer that tastes good on its own, has soured and aged properly. Our fruited styles are really showcasing the fruit flavors, so we want the additional tartness in the base beer, but the specific base beer flavors usually get overrun by the fruit. Now when we select barrels for Sour Reserve, which is an unfruited blend of one to three year old base beer, we try to select barrels with our favorite flavors, and different flavors, so we end up with a layered and complex profile in the final blend.

What precautions or troublesome areas have you run into when creating fruit sours, any advice for overcoming these?

- I can’t think of anything that wasn’t worth the effort at the end of the day. Being stubborn and peeling 1500 lbs. of whole kiwis by hand always seems a bit absurd, but we do it because we think it makes a better beer. We’ve started playing around with dried fruits and purees, but that will be utilized to make newer sour beers in our lineup. We’re aligned on the traditional style fruited sours to be as traditionally made as possible, even if it requires more effort. I would say there is quite a bit of haze involved when you add as much fruit as we do, but working with various methods of clarification, those types of issues can be remedied.

Again, I would like to thank Caleb very much for sharing his knowledge and experience with our readers!